The refugee crisis is becoming increasingly politicized; less about the safe guarding of human rights and more about the safe guarding of national borders. Though forced migration is nothing new, the numbers are unprecedented; 65.3 million people around the world are currently displaced by war or persecution, according to the UNHCR. It’s a modern problem of biblical proportions and as the figures rise, the individual refugee is increasingly regarded as little more than a troubling statistic.

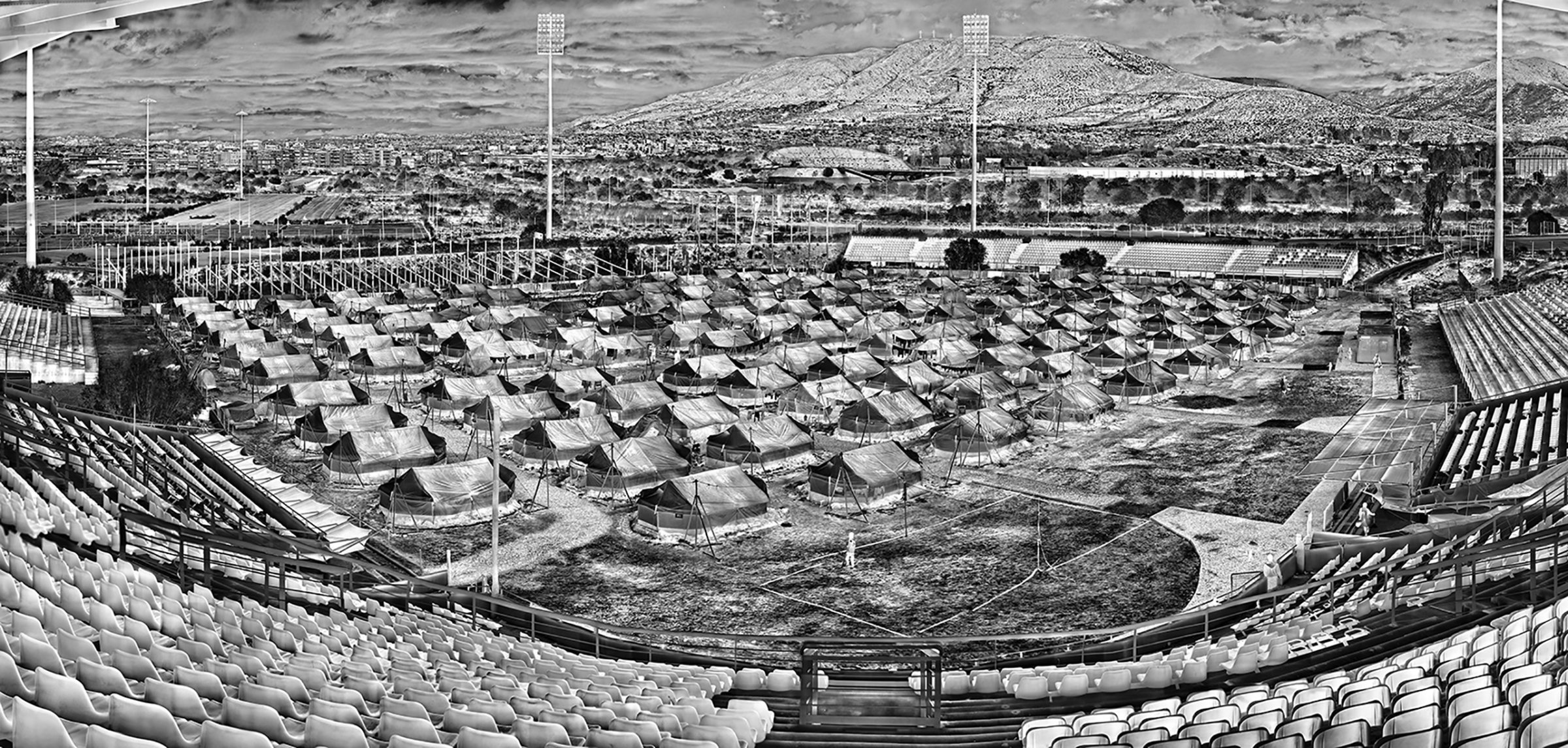

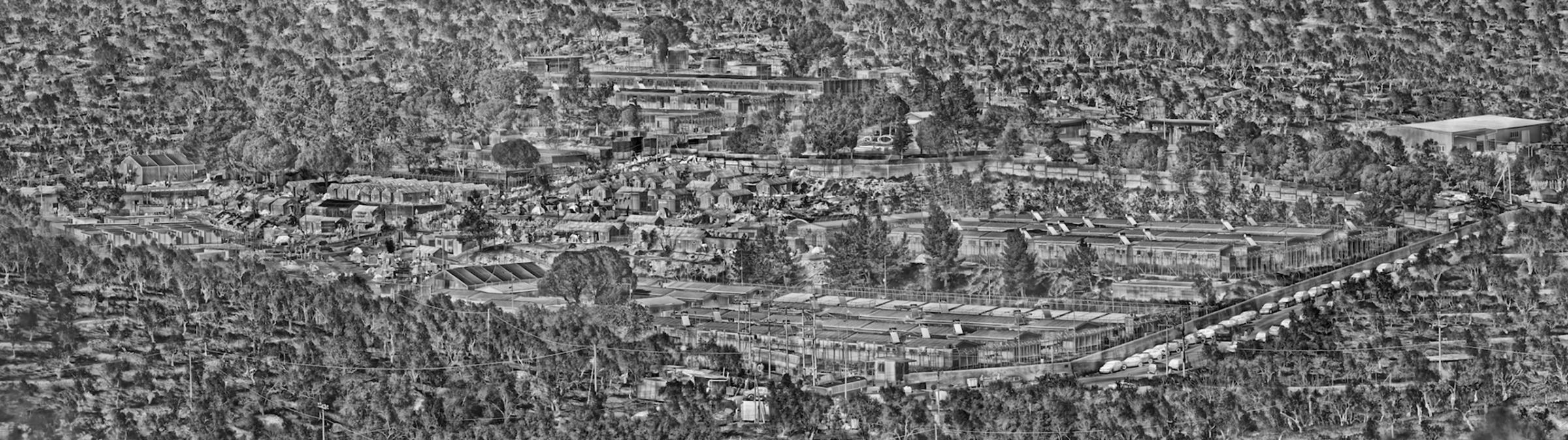

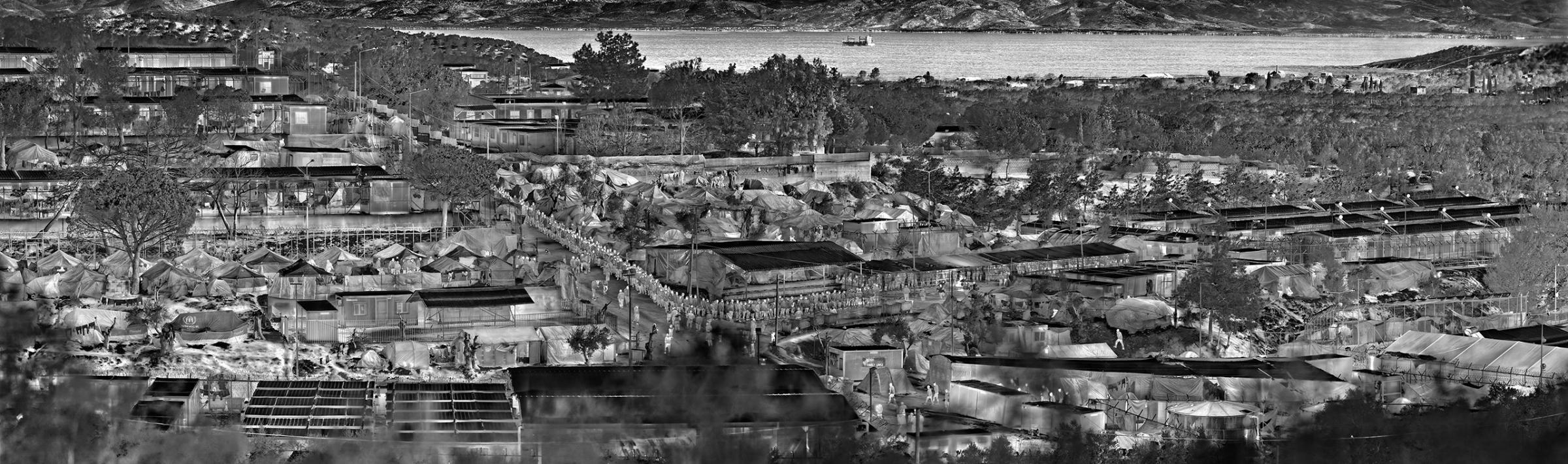

Photographer Richard Mosse’s latest project, Heat Maps, offers an unconventional take on a much-dissected subject. The work charts the refugee crisis unfolding across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East using a powerful military grade telephoto camera attached to a robotic arm which detects thermal radiation by scanning landscapes and interiors. The result is unsettling; human flesh is turned a translucent grey, eye sockets are blackened, bodies appear like avatars existing in a virtual dystopia.

The paradox is, life in these refugee camps can be just as hellish and dehumanizing as the photographs imply. “It’s a camera that strips people of their identity. It turns them into a creature or a biological trace,” Mosse tells TIME. “I hope that the camera will reveal the way we in the West and our governments represent and therefore regard the refugee.” Deliberately disconcerting, Mosse wants the viewer to feel an uneasy sense of their own complicity. “The horrific conditions in those camps are created by our governments. And we vote those people in,” he adds.

Heat Maps isn’t easily classified, perching as it does between factual surveillance, aesthetic ambiguity and the fantasy-world of a Ray Bradbury novel. But it’s supposed to be polyvalent, ambivalent, open-ended. “It’s meant to force the viewer into a place where they have to decide what it is,” says Mosse. “Because with the refugee crisis, everyone has already made up their mind.” Though the photos are revealing of the refugees’ situation, the individual characters technically remain indistinguishable. While Ai Weiwei was refused access photographing the interior of Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport – now Germany’s largest refugee camp – Mosse was admitted, because he could show how the camera left the subjects identities in tact. But taken at long range – as far away as 50 kilometers – there is still a degree of violation. “You’re not quite committing an invasion of privacy, yet you are,” he says.

The photographs are impressive online but humbling in person; the large-scale panoramas take up most of a gallery wall. They evoke the detail of a Bruegel painting but the flatness of a Medieval tapestry; an array of miniature scenes impossibly arranged into one prevailing landscape. The large-scale pieces are technically ‘photo-illustration’ and are constructed from a grid of almost a thousand smaller frames – each with their own vanishing point – painstakingly sewn together.

The work is a surveillance of the grim squalor of the camps but cannot be read as an exact reality. Amid the complex scenes, an occasional figure will stand dismembered – the result of a glitch in the camera’s heat scanning that Mosse decided to leave in. “Being a refugee strips you of the inalienable rights of man, which are subsumed into the idea of a citizen,” Mosse says. “Once you’ve left your nation state due to persecution, conflict, climate change, you lose your human rights.”

The violent aesthetic of the images is not without context. Primarily designed for surveillance, the camera can also be connected to a weapons system to target the enemy. The misuse of its intended purpose is another deliberate attempt to subvert the common perception of the refugee. “I’m trying to use these sinister technologies against their original intended purpose,” he says. This is ironic considering the call made by German far-right leader Frauke Petry to use firearms on illegal refugees “if necessary.” Quoting the work of Allan Sekula, Mosse believes his role as an artist is to try to “brush photography against the grain”. It’s a method he’s adopted before with his Infra series; a psychedelic vision of the Democratic Republic of Congo conflict taken with a discontinued surveillance film originally used by the military. Both projects employ the Brechtian ‘Verfremdungseffekt’ – or distancing effect – which serves to make the familiar strange. “I put the viewer in a space where they have no cues, they don’t understand the grammar of the language,” he says. “So they have to actually engage with this on an unfamiliar level and as a result, it’s fresh.”

Unlike the hyper-local Infra, Mosse worked across many, dislocated landscapes. “These people are dispossessed, they’re displaced,” he says. “You can’t really predict where the story will flash up next. You have to keep your ears to the ground. ” Complex logistics plagued the three-year project. Mosse built up a network of volunteers and fixers but access was often difficult, particularly in the Calais Jungle, which they eventually infiltrated right before it was dismantled. Outside Europe, attempting to cross borders was mired in deadlock. When Mosse and his team were trying to reach Timbuktu through Mali, they spent a month – without success – trying to permeate a Swedish battalion, hoping to make use of their convoys. But these stumbling blocks were part of the process and the constant challenges forced Mosse into a space of hyperawareness.

Navigating sticky border control ran parallel to navigating tricky equipment. Attached to the already complex telephoto camera was a tangle of wires and cables that connected to an X-Box controller, media recorder and several laptops. “You really need to earn your chops with [the camera],” he says. “And you constantly feel slightly compromised by what you’re doing. But I think that’s always a good space to be in as an artist: feeling uncomfortable.” Mosse witnessed some horrific scenes, impossible to express through the prism of art. But, he says, once you’re looking through the ground glass of the camera you become a machine with a job to do. “I cling to the idea that although ‘art is useless’, it can be iconic,” he says. “It can be culturally resonant without being politically committed.”

Richard Mosse is an Irish conceptual documentary photographer. More of his work can be viewed here. Heat Maps is on display at the Jack Shainman Gallery on West 20th Street, NYC until March 11.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com