Campbell is a U.S.-based attorney who represents Uzbek activists in negotiations between the U.S. Dept. of Justice and Uzbek government.

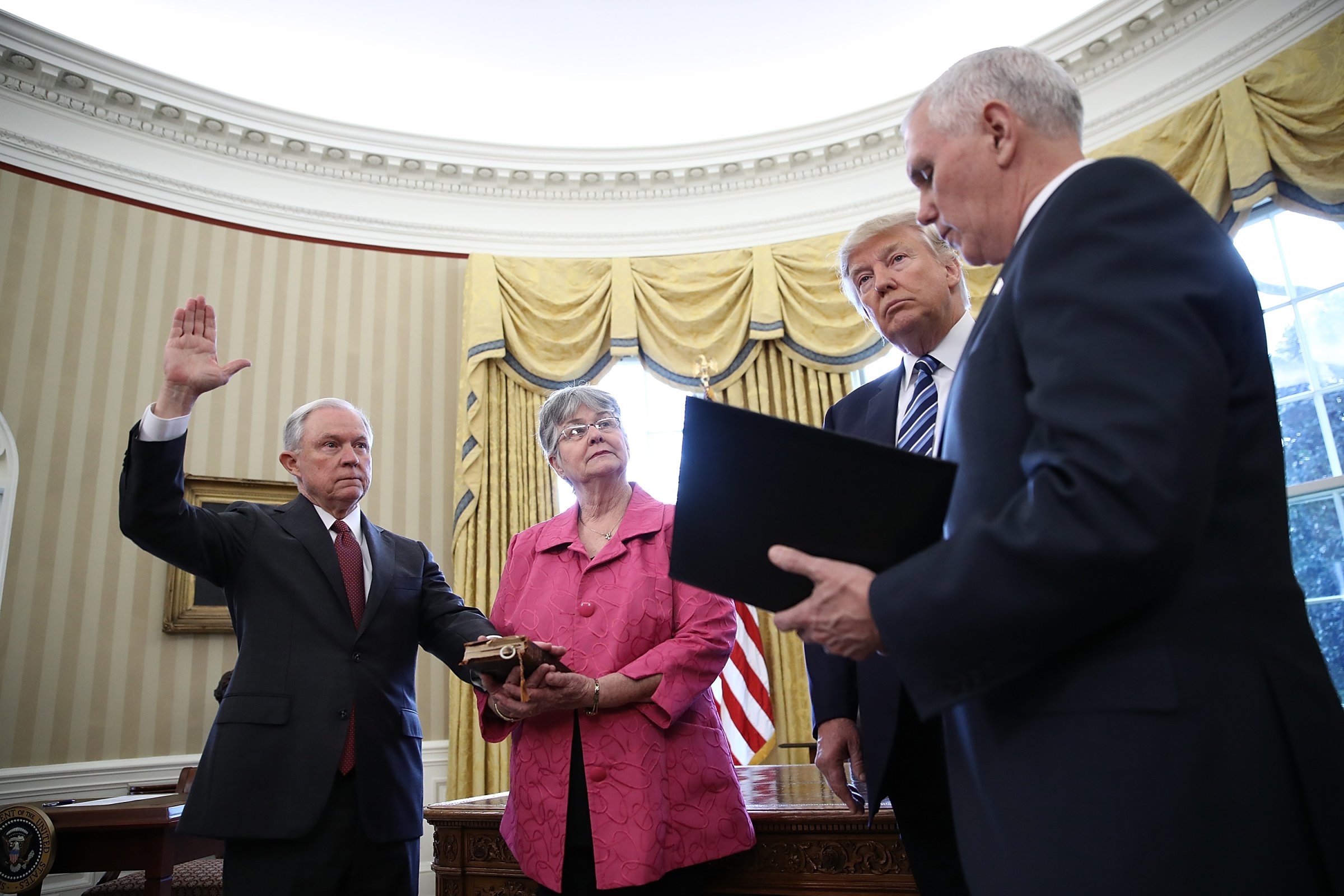

During Senator Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearings for Attorney General, three words came up again and again: “rule of law.” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell took to the Senate floor to praise Sessions as “someone who believes strongly in the rule of law.” Proponents of Sessions’ nomination have consistently cited his belief in the rule of law. It is his ostensible conviction that government, its officials and agents, as well as individuals and private entities, are accountable under the law.

As Sessions takes the helm the Department of Justice, among the first challenges the DOJ will face in honoring — and implementing — the rule of law will be its pursuit of $850 million stemming from corrupt telecom deals in Uzbekistan.

The Justice Department’s Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative, which works to “forfeit the proceeds of foreign official corruption and, where appropriate, use those recovered assets to benefit the people harmed by corruption and abuse of office,” has asked a federal court to freeze the $850 million. It is a portion of the proceeds from a complex bribery scheme involving high-level Uzbek government officials, who sold access to the country’s telecommunications market to foreign companies. In 2016, the Kleptocracy Unit successfully secured a conviction of one of the companies involved, VimpelCom-owned Unitel, which was charged with a conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

The government of Uzbekistan, however, has intervened in the case. It seeks to recover the $850 million by arguing, without providing any evidence, that it has brought the perpetrators to justice in a trial that ostensibly took place in July 2015. Meanwhile, the Uzbek government’s letter to the court failed to say anything about its efforts to pursue justice against key officials involved in the case, including Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of Uzbekistan’s late president. As is common in the U.S. justice system, the court has requested that the Justice Department and Uzbekistan seek a negotiated settlement for the return of the frozen assets rather than proceed through what could be long, expensive litigation. Trump’s Administration, with Sessions’ supervision, will inherit these negotiations at the end of the month.

Settlement with the government of Uzbekistan could prove very difficult for a Justice Department seeking to adhere to Sessions’ stated goals. It is hard to find a more corrupt government than Uzbekistan’s. “Rule of law” is a concept its officials have been evading for decades: Transparency International ranks Uzbekistan 156 out of 176 countries in its Corruption Perception Index.

This corruption isn’t limited to a few top government officials. It is systemic and systematic, running through every level of government. Uzbek citizens suffer from human rights abuses, torture, forced labor and unfair arrests at the hands of the government.

The decision to freeze the $850 million was a critical blow to Uzbekistan and corrupt regimes worldwide. It was a first step. U.S. officials have indicated that they want to return the money to Uzbekistan. But there are deep concerns about who will receive the money, how it will be disbursed and what sort of oversight there will be.

What the Trump Administration — and Sessions — decide to do with the money will shed light both on how seriously the Administration intends to enforce the rule of law as well as its commitment to holding corrupt regimes accountable — in Uzbekistan, but also in Ukraine, Malaysia and across the world.

If Sessions truly believes in the rule of law, and truly intends to preserve global security and enforce the FCPA, the way forward is clear: The money cannot be returned to the government of Uzbekistan. Doing so would line the pockets of the same corrupt officials who stole the money in the first place.

Returning the money to the Uzbek government would also carry serious geopolitical ramifications. The country’s systemic corruption fuels disenfranchisement among its population. This is especially true for citizens who are the most impoverished and alienated — and therefore most vulnerable to radicalization. Returning the frozen assets to the Uzbek government would also breed further disillusionment among the Uzbek people and open the door to radicalization, militancy and destabilization in Central Asia and beyond.

Moreover, corrupt and unaccountable assets easily find their way into organized crime networks, and may thereby fuel militant groups that pose a threat to the United States. There is evidence that the Uzbek government not only has ties to bosses of organized crime, but has used these connections to hire criminals to hunt opponents of the regime.

Instead, the money should be returned to the people of Uzbekistan, the true victims of decades of corruption and human rights violations. This could set a new international standard, provide a clear means to challenge impunity and bring justice to victims of corruption both in Uzbekistan and around the world.

There is precedent for this kind of successful asset repatriation: It could be achieved through setting up a charitable fund, similar to the BOTA Fund in Kazakhstan, which would direct the assets to victims of torture and other social services in the country.

Unfortunately, the utter lack of civil society and democratic institutions in Uzbekistan makes executing and monitoring such a fund impossible. Until real reforms happen within Uzbekistan, the Justice Department should place the money in a transparent trust that is accountable to the people of Uzbekistan, and which could increase in value over time. It is the only feasible option given the current climate.

This is a chance for the Trump Administration to deter corruption, hold offenders accountable and to send a clear message to the international community: No one is above the law.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com