In the days since assuming the presidency, Donald Trump has worked quickly to transform his campaign promises on immigration into policy. So far, the most dramatic of these policy roll-outs has been Trump’s recent ban on immigration from seven predominantly-Muslim countries. But, should he continue to make good on his election-season statements, another controversial policy may lie ahead: a long-promised crackdown on sanctuary cities.

What form this crackdown will ultimately assume remains to be seen, but he has already issued an Executive Order promising to withhold federal funds from municipalities that refuse to assist federal immigration law enforcement, and on Sunday he reiterated that threat in an interview with Fox News. During his presidential campaign, moreover, Trump often discussed plans to create a federal “deportation force.” And following his November election, Trump tapped Kris Kobach — author of Arizona’s controversial “Papers Please” law — for his transition team. Meanwhile, a wide range of localities have signaled their support or disapproval of the idea: for example, Bozeman officials are considering becoming Montana’s first sanctuary city, even as Ohio legislators consider banning sanctuary cities in their state.

Before moving forward, however, those who support policies that make it difficult for cities to protect undocumented immigrants might consider the fallout from the infamous Fugitive Slave Act.

Passed in September of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was part of a bundle of laws that legal historian Paul Finkelman calls the “Appeasement of 1850,” designed to placate southerners spooked by northern efforts to ban slavery in land that had been snatched from Mexico during the recent U.S.-Mexico War. The law achieved this goal by lending the full weight of the federal government to recapturing escaped slaves, even after the fugitives had made it to states where slavery was banned.

It did this in several ways. First, the law imposed fines and jailtime on individuals abetting fugitives’ flight. Second, it required local law enforcement officers (and even private citizens) to actively abet slaveholders’ efforts to recapture their so-called human property — despite legislation, known as “Personal Liberty Laws,” that in some states specifically absolved law enforcement of that obligation. And third, the law created a network of specially-appointed magistrates tasked with determining whether those targeted by the law were, in fact, fugitives from bondage. To ensure these courts produced the outcome slaveholders wanted, the Fugitive Slave Act banned African-Americans’ testimony in their own defense and created financial incentives for magistrates who found in slaveholders’ favor.

In the three months after the Fugitive Slave Act’s passage, some 3,000 escapees, living precarious lives as free people in the North, fled to Canada. Meanwhile, other African-Americans as well as their white abolitionist allies complained that the law practically begged unscrupulous characters to kidnap free people of color—the long-standing practice that, a decade earlier, had subjected Solomon Northup to his “Twelve Years a Slave.” And even moderate whites, ordinarily unconcerned with slavery and enslaved people, objected to the Fugitive Slave Act as an affront to due process, states’ rights and liberty of conscience.

The backlash against the law was powerful and immediate, and had little, if any precedent, in American history to date. Massive petitions arrived in Congress, angry missives inundated Senators and Representatives, outrage filled the columns of northern newspapers and protests packed the streets.

This backlash, however, was not limited to the formal realm of protests and petition. In September of 1851, free and escaped African-Americans living in Christiana, Penn., opened fire on a federal posse, killing a Maryland slaveholder who had come north seeking a fugitive. Just under a month later, black and white abolitionists in Syracuse, N.Y., broke down the doors of a jail where accused fugitive William Henry was being held and spirited him to freedom. And by the end of that year, Harriet Beecher Stowe was captivating northern readers with a serialized novel that focused, in part, on a young woman and her child as they fled from merciless agents of the Fugitive Slave Act. That novel, of course, was Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Perhaps the most dramatic backlash against the Fugitive Slave Act took place in 1854. In February of that year, a 19-year-old fugitive named Anthony Burns arrived in Boston after a harrowing, three-week sea journey from Richmond. Hiding in a space no larger than a coffin, Burns had nearly starved and frozen to death during his storm-tossed odyssey to the North.

Upon arriving, Burns worked hard to blend in among the city’s free black community. But, by May, he was in the clutches of a slavecatcher hired by his owner. Boston’s black and white radicals, however, refused to let Burns’ captor re-enslave him without a fight. Hoping to repeat the rescue of William Henry in Syracuse, Bay City abolitions advocated rescuing the fugitive by force. Taking to the streets, these abolitionists — including Emily Dickinson’s confidante Thomas Wentworth Higginson — broke into the city jail but were repulsed by police before they could free Burns.

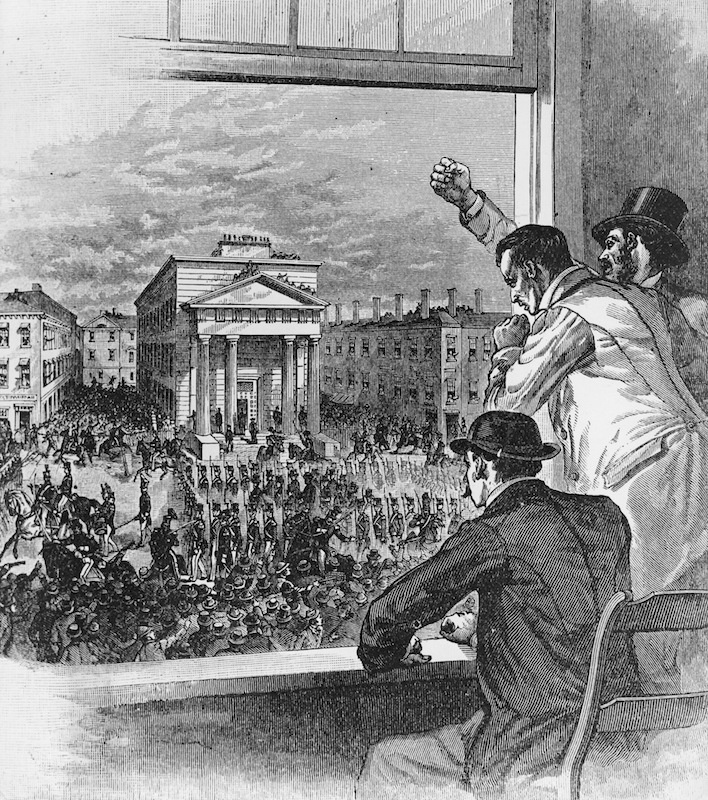

Over the following days, as a federal marshal was deciding Burns’ fate, federal troops — as well as local and state units mobilized under the 1850 legislation — transformed Boston into an occupied city. Outside the Boston courthouse, artillerymen mounted cannon and ran through the motions of firing on civilians. By the end of that month, the marshal had condemned Burns to bondage. But Bostonians continued to resist, protesting en masse as Burns was escorted to a ship headed for Virginia—bound back to the captivity from whence supporters would ultimately buy his freedom.

All told, the scene had marked the largest peacetime military deployment in American history to that date.

In important respects, however, these scenes — a ferocious backlash that has already been compared to the reaction to Trump’s recent immigration order — merely hint at the long-term fallout of the Fugitive Slave Act. In the years following its passage, northerners learned crucial political lessons from the act, lessons that fueled their resistance to slaveholders’ power and led directly to the Civil War.

First, the Fugitive Slave Act disabused northerners of the notion that slavery was a distant institution. For years, northerners had deluded themselves into believing that they bore no direct responsibility for human bondage. The Fugitive Slave Act, by contrast, demonstrated that slavery’s existence required complicity and cooperation from Americans everywhere.

The legislation also reminded white northerners that slavery ultimately rested on a foundation of violence. Many northerners, prior to the 1850s, were willing to believe that enslaved people were, as southern whites insisted, happy with their lot, and that slaveholders rarely required the lash, pistol or noose to maintain their authority. Here, too, the Fugitive Slave Act deprived white northerners of their illusions by confronting them with spectacles of violence in their own backyards.

Lastly, the Fugitive Slave Act showed white northerners that they could build a viable antislavery coalition on non-humanitarian grounds. Many antebellum white northerners were hostile to black liberty and dignity — unmoved by the travails of Eliza and Harry in Uncle Tom’s Cabin or by Anthony Burns’ brutal rendition in Boston — but even they could be affected by the notion that a powerful cabal of southern aristocrats had perverted due process, states’ rights and individual liberty. These racist opponents of the Fugitive Slave Act would never become committed abolitionists; but they would, by decade’s end, join a newly-created Republican Party committed to defeating the so-called “Slave Power.”

Trump’s proposed sanctuary-city crackdown would, it appears, bear many similarities to the Fugitive Slave Act. Like the 1850 law, it would move a controversial area of the law — immigration regulations, and the often violent way in which they can be enforced — away from the abstract realm to the concrete reality of major American cities. It would also, like the 1850 law, create common ground between activists on the issue and those who are merely opponents of federal encroachment.

And so those who would support a sanctuary-city crackdown might recall the long-term consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act for its authors and supporters. After enjoying their brief moment of triumph, proslavery ideologues quickly found themselves confronted by increasingly radical and powerful opponents. Fifteen years later, the ashes of their erstwhile estates littered the southern soil. And the people they had fought to keep in chains bore arms against them — by the hundreds of thousands — in the greatest struggle in their nation’s history.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sean Trainor has a Ph.D. in History & Women’s Studies from Penn State University. He teaches history and humanities at Santa Fe College and blogs at seantrainor.org.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com