The next chapter of Snapchat’s life will begin over the coming months, as parent company Snap, Inc. goes public with an initial offering that could value the firm at approximately $20 billion. Success is far from certain: The Venice Beach, Calif.-based Snap has warned in investor documents that it could lose users to competitors with “greater resources and broader global recognition” — shorthand for the Facebook-owned Instagram. Snapchat’s once-meteoric growth is showing signs of slowing, with only 8 million new users over the last six months.

But whether or not Snapchat survives in a competitive market in the coming years, its contributions — along with those of rivals like Instagram and Apple — to the medium of photography and visual communication are unprecedented. Snap put it this way in its IPO documents: “In the way that the flashing cursor became the starting point for most products on desktop computers, we believe that the camera screen will be the starting point for most products on smartphones.”

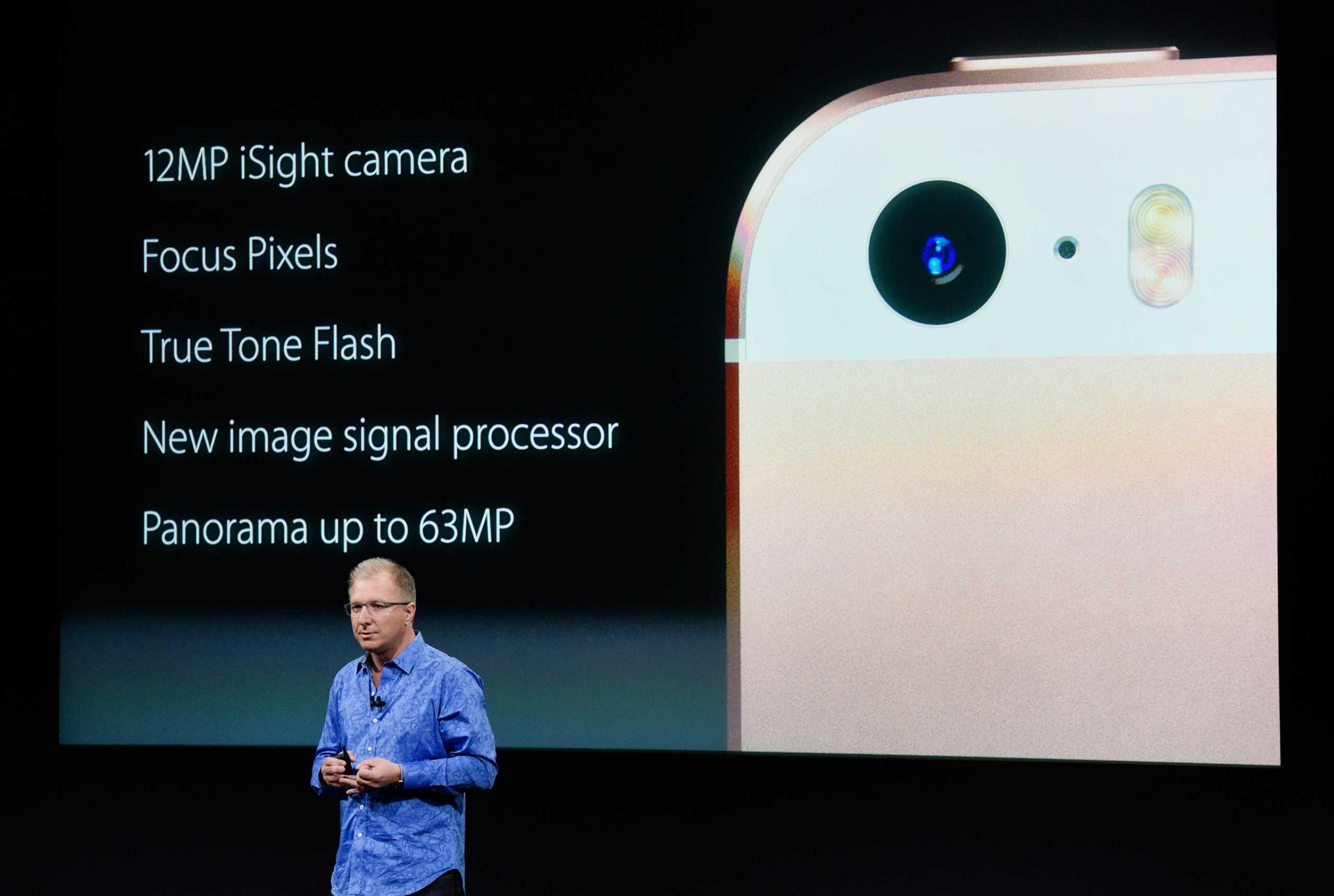

It’s that approach that has changed the way we communicate with imagery. It started with phone manufacturers like Apple, which, in response to traditional camera makers, chose to buck the trend by drastically simplifying the photographic experience. “We want to make it so it’s a single tap and you get the picture you want, even though, in the background, we’re doing literally one hundred billion operations to make that photo look as good as it possibly can look,” says Greg Joswiak, Apple’s vice president of product marketing.

The simplicity of the iPhone camera app was a game changer at a time when being a serious photographer typically meant mastering wonky settings like ISO, aperture and shutter speed, not to mention the dozens of other features available on traditional cameras.

By simplifying the camera experience and embedding it in a device that we all carry with us, companies like Apple and Samsung have helped establish the image as a primary form of communication today. “I grew up with technology,” says Robby Stein, Instagram’s product lead for its Snapchat-like Stories feature. “The first thing that we had was the desktop computer and so we were on Instant Messenger, we were sending emails. The way you were communicating was very much based on a keyboard, based on text.” But today’s generation is growing up with a phone-sized computer in their pockets, he says. “Their first device is a camera and they have it in their pocket all the time to capture and share their lives.”

As a result, that camera-first approach is changing the function of the photograph itself. It’s not just the historical record of a past event, says Stein, but it can also be the starting point of communication. “It might not just be the photo itself that’s interesting, but it’s also the context around it,” he tells TIME. “Whom you’re with. What the weather is. How you’re feeling.”

For Snapchat, the camera is the launch point for interactive experiences, as CEO Evan Spiegel explained in a video for prospective investors released ahead of its IPO. Providing that context is at the center of Snapchat’s experience. Snapchat was the first mainstream app to popularize this new format for the photograph. Users can add location tags, mood stickers and filters, as well as other contextualizing information like temperature, time and speed, to photographs and videos. Rival apps have since aped those features.

Most importantly, Snapchat says it removed the “baggage” from the act of photographing by making images ephemeral. “Everyone thought of cameras as a way to save very important memories,” says Spielgel in the investor video. “So when we created Snapchat where everything is deleted by default . . . we had to explain that Snapchat is used for communicating, it’s used for talking. We find that conversation is more comfortable, more familiar and natural when it deletes by default. Self-expression isn’t a contest. It’s not about how well you can express yourself, it’s about being able to communicate how you feel and doing that in the moment.”

Snapchat was so successful with this new approach to communication – growing to 150 million daily users in just five years – that Instagram copied it, launching a similar feature called Stories last November. “That’s the biggest shift we’ve seen and we’re building products to enable that type of visual communication,” says Instagram’s Stein. But that doesn’t mean that Instagram is erasing its past as a place for photographic memories. “For us, there’s a natural complement between sharing a lot of the highlights of your life and sharing much more of your life in the moment, as it’s happening, which is what Stories has provided,” adds Stein.

What Snapchat and Instagram are getting right is that the best camera isn’t the one you have with you, as the saying goes, but it’s the one that comes with your community of people. “A lot of the time, you take a photo or a video with the explicit purpose of sharing it,” says Stein. “So, the best camera is one that is connected to your friends, allows you to create and express yourself and allows you to do that very easily and quickly. That’s why we’re seeing the importance of all of those structures coming together.”

There’s no sign this “connected camera” trend will stop. As smartphones continue to improve beyond their own hardware limitations and through new software updates and APIs (“We continue to look at not just the improvements that we make to our own camera and photo software, but making sure we’re providing powerful APIs for our third parties,” says Apple’s Joswiak.), companies like Snapchat and Instagram will continue to rewrite the definition of photography.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com