In the wake of President Donald Trump’s executive order on immigration Friday, many critics quickly took up a familiar rallying cry, lifting words from the Statue of Liberty that have for decades represented American immigration: “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

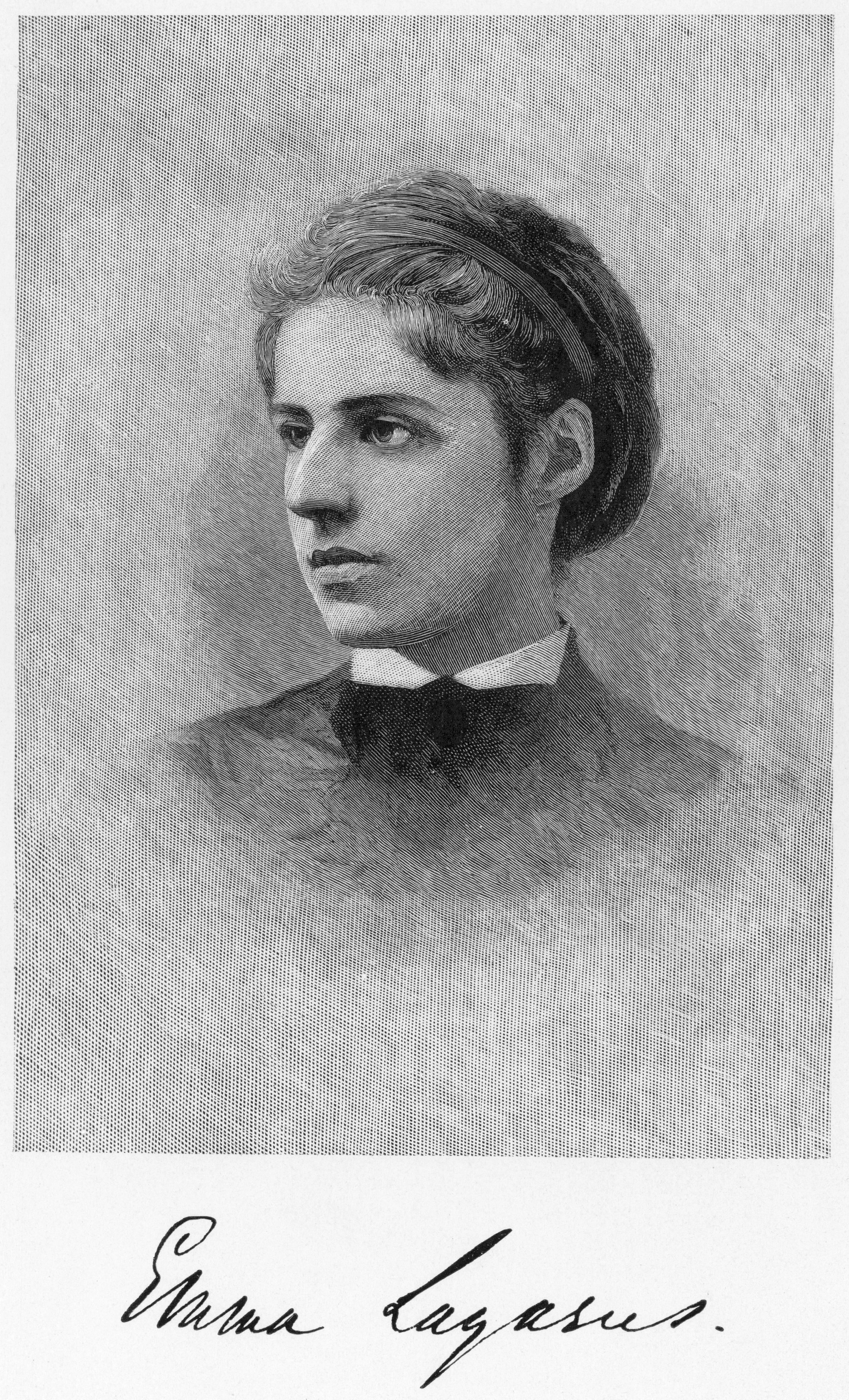

Former independent presidential candidate Evan McMullin, Minnesota Rep. Keith Ellison and former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright all invoked those words — written by American author and poet Emma Lazarus in 1883 — as they condemned Trump’s suspension of the country’s refugee assistance program.

Richard Spencer — the alt-right leader and white nationalist who last week unwittingly launched an internet debate over whether it’s OK to punch a Nazi — responded by criticizing the famous poem.

“It’s offensive that such a beautiful, inspiring statue was ever associated with ugliness, weakness, and deformity,” Spencer said in a tweet Saturday.

But the statue was not initially met with widespread popularity in the U.S. due to its cost, and some have argued that Lazarus’ sonnet, “The New Colossus,” actually imbued it with meaning.

The poet James Russell Lowell said he liked the poem “much better than I like the Statue itself” because it “gives its subject a raison d’être which it wanted before,” according to the New York Times.

“Emma Lazarus was the first American to make any sense of this statue,” Esther Schor, who wrote a biography on Lazarus, told the Times in 2011.

Lazarus, who was born in New York City in 1849 to a wealthy Jewish family, composed “The New Colossus” for a fundraiser benefiting the Statue of Liberty in 1883. (While the statue was a gift from France, the United States was responsible for covering the cost of its base and pedestal.)

Lazarus drew inspiration from her Sephardic Jewish heritage and from her work on Ward’s Island, where she helped Jewish refugees who had been detained by immigration authorities, according to the National Park Service.

“Wherever there is humanity, there is the theme for a great poem,” she once said, according to the Jewish Women’s Archives.

The poem was later published in New York World and the New York Times, just a few years before Lazarus died in 1887.

The Statue of Liberty arrived in New York in 1885 and was officially unveiled in 1886, but Lazarus’ poem did not become famous until years later, when in 1901, it was rediscovered by her friend Georgina Schuyler. In 1903, the last lines of the poem were engraved on a plaque and placed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, where it remains today.

The poem, in its entirety, is below:

The New Colossus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com