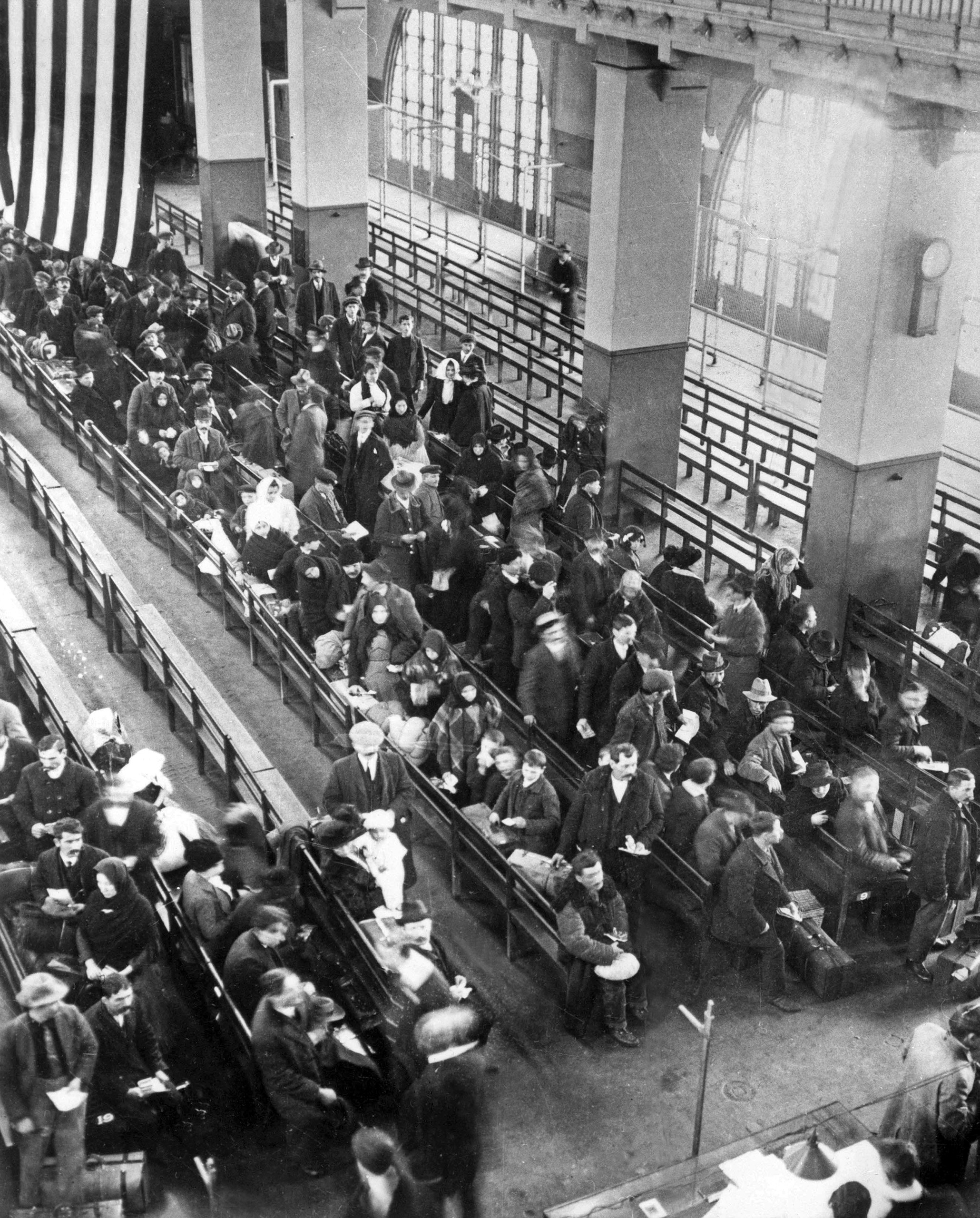

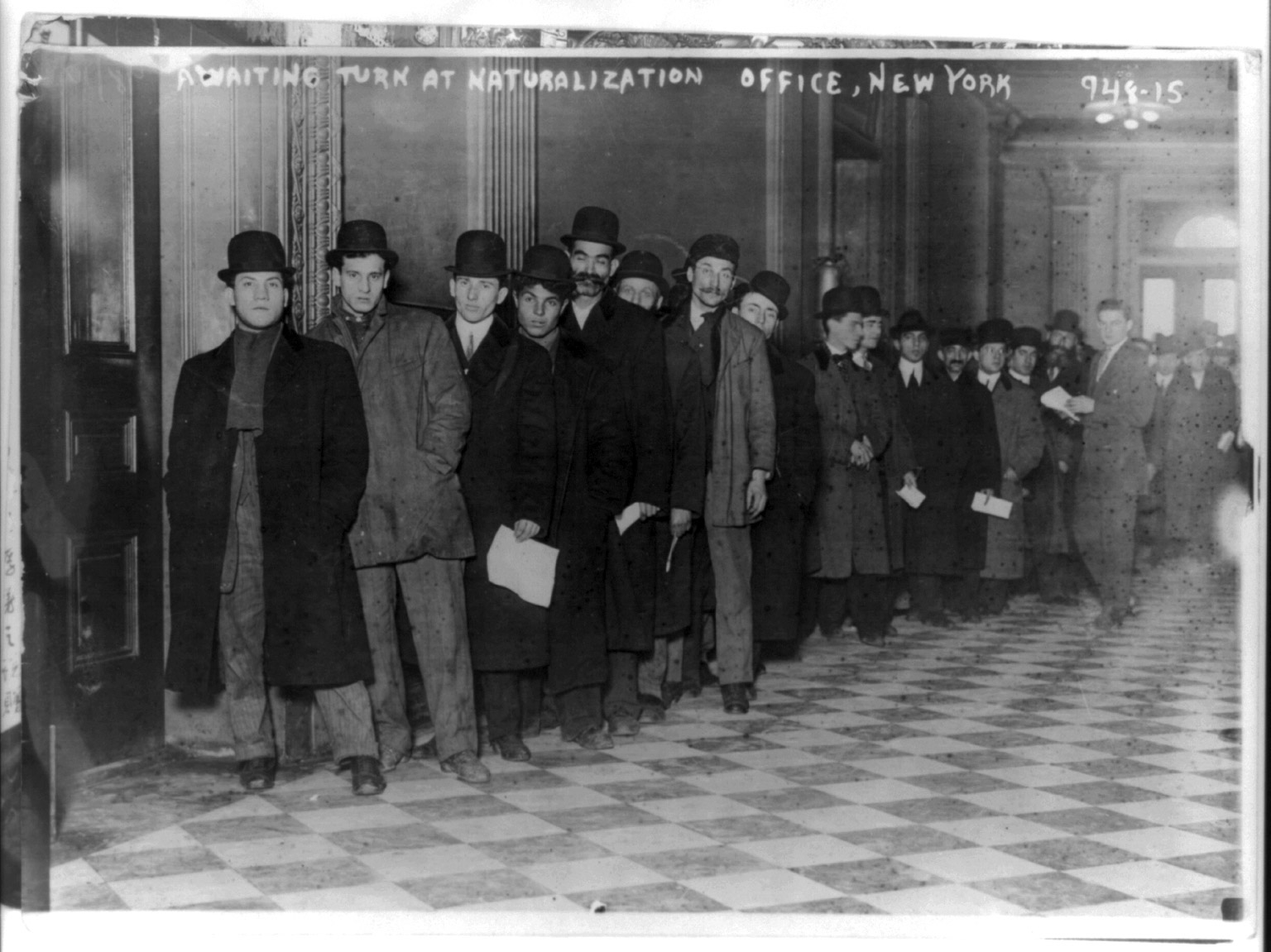

It was 100 years ago this Sunday, on Feb. 5, 1917, that the U.S passed what was at the time the nation’s strictest-ever regulation of immigration. And there’s a reason why the 1917 Immigration Act goes by many names, like the Literacy Act and the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. It changed the state of American immigration in the 1910s, the decade represented in the photos seen here—though the rules would get even more restrictive in the years to come.

The 1917 law, which passed over multiple vetoes by President Woodrow Wilson, raised the tax imposed on most adult immigrants, and also imposed several kinds of restrictions on the people who were allowed to come to the U.S.

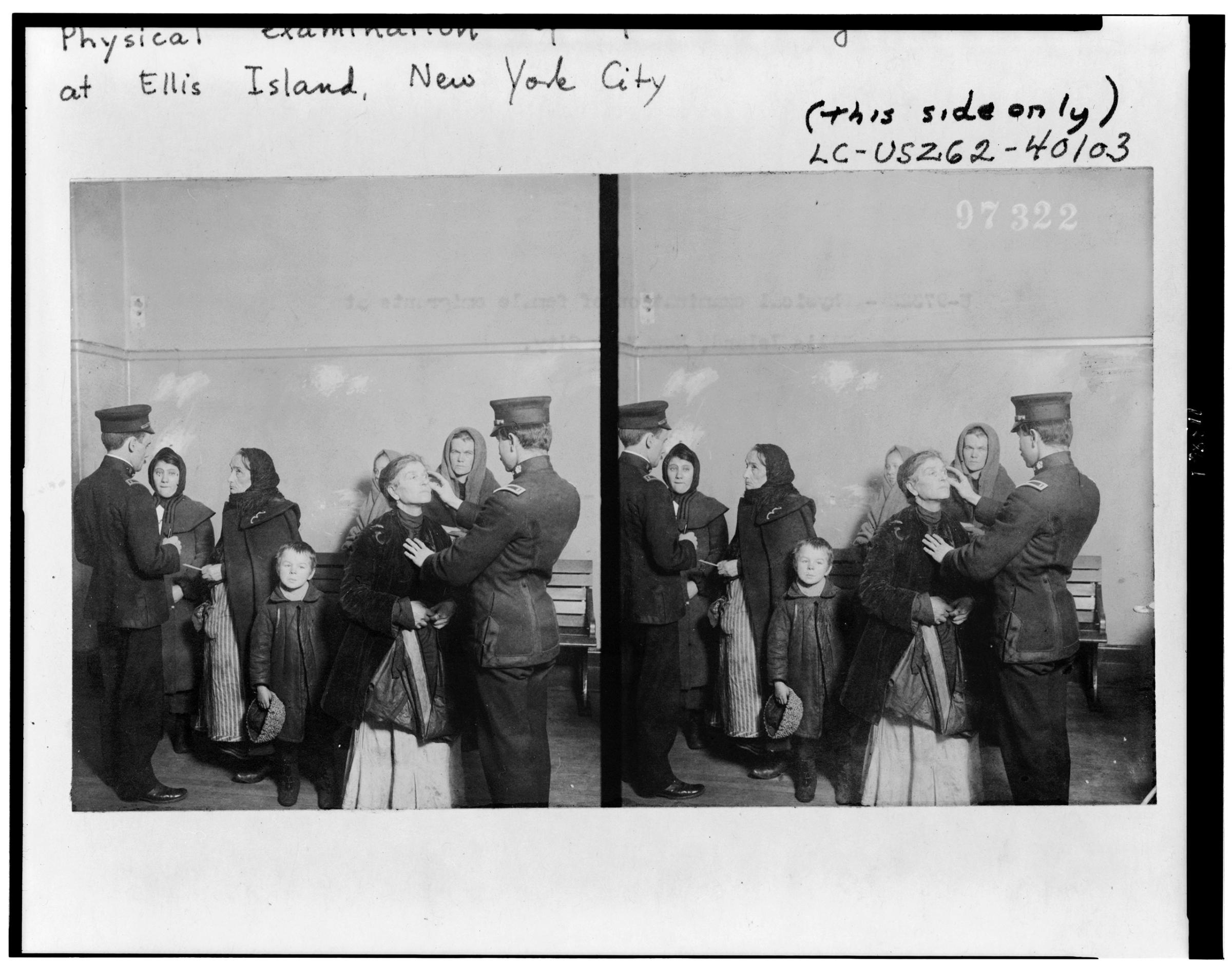

Excluded from entry in 1917 were not only convicted criminals, chronic alcoholics and people with contagious diseases, but also people with epilepsy, anarchists, most people who couldn’t read and almost everyone from Asia, as well as laborers who were “induced, assisted, encouraged, or solicited to migrate to this country by offers or promises of employment, whether such offers or promises are true or false” and “persons likely to become a public charge.”

Some of those restrictions were echoed nearly verbatim this week in as reports that the White House is considering further restricting immigration in order to “deny admission to any alien who is likely to become a public charge” and get rid of the “jobs magnet” attracting immigrants, per the Washington Post‘s coverage of drafts of possible executive orders.

As the State Department Office of the Historian has pointed out, one concern used to push the bill through Congress in 1917 was the question of security during the era of World War I, which the U.S. would formally enter a few months later. In fact, however, the war had already significantly depressed immigration from Europe before the law was passed, with no regulation needed.

And the war does not explain the law’s focus on Asian immigration, only the latest in a long string of racist restrictions on immigration across the Pacific: Chinese immigrants had already been limited in the 1880s by the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prevented Chinese laborers from coming to the U.S. and remained on the books for more than 50 years, and immigration from Japan was kept low due to a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” between the two nations, made a decade before the 1917 law.

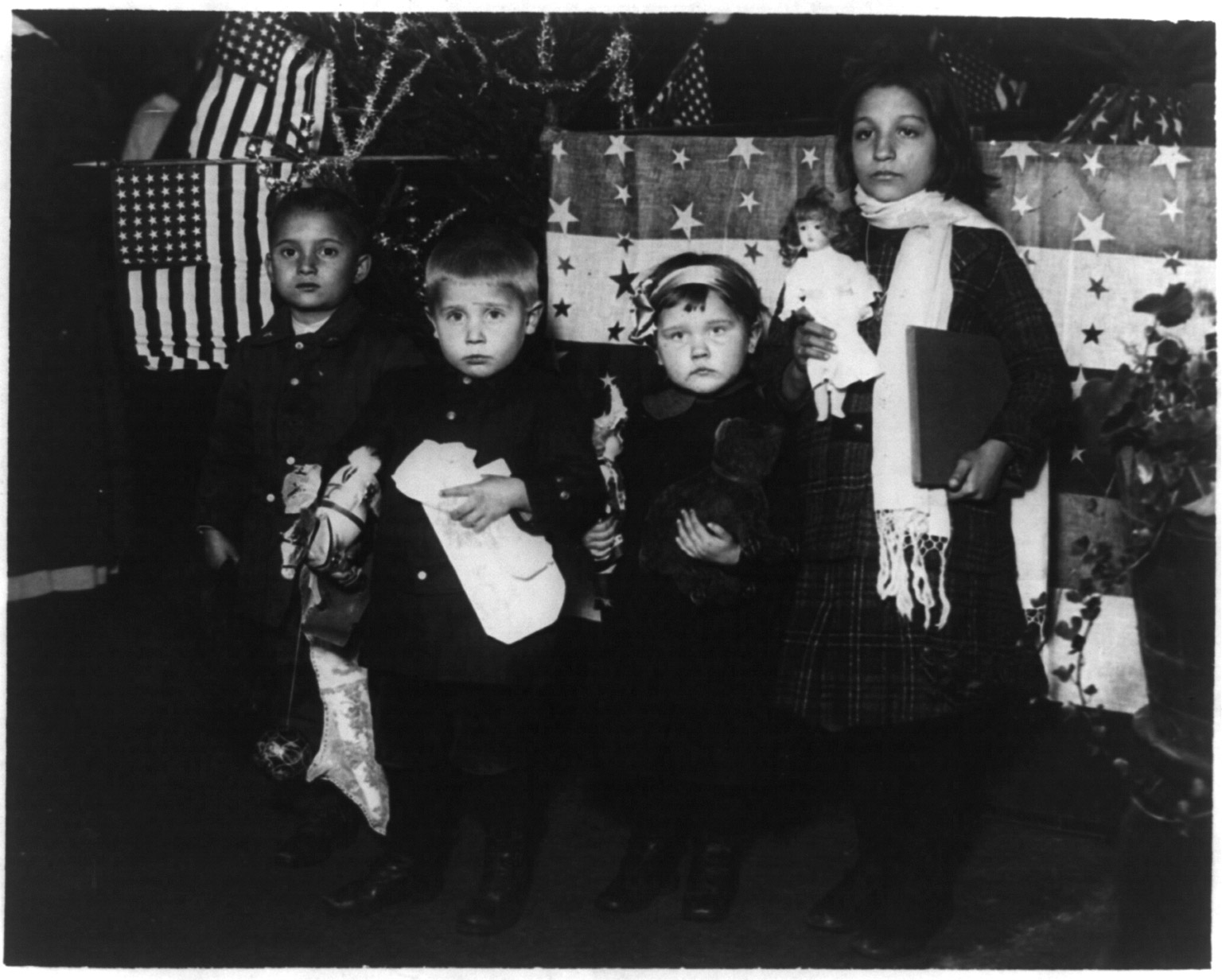

Some at the time focused on the literacy test, something that would “affect so large a proportion of the ordinary immigration stream so as to be really restrictive,” as one writer put it, as the part of the the law that most illuminated its true purpose. The 1917 law was seen by them as a crystallization of a trend that had been a long time coming: the U.S. was turning inward, and many were ready to shut out the world—and to shut out the people, like the ones seen here, who wanted to become American.

Not everyone thought that was a good idea, however.

“Restrictions like these, adopted earlier in our history as a Nation, would very materially have altered the course and cooled the humane ardors of our politics,” wrote Woodrow Wilson upon vetoing a version of the act in 1915. “The right of political asylum has brought to this country many a man of noble character and elevated purpose who was marked as an outlaw in his own less fortunate land, and who has yet become an ornament to our citizenship and to our public councils. The children and the compatriots of these illustrious Americans must stand amazed to see the representatives of their Nation now resolved, in the fullness of our national strength and at the maturity of our great institutions, to risk turning such men back from our shores without test of quality or purpose.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com