Though many Australians will celebrate their national holiday on Thursday with fun events like barbecue and fireworks, the history behind the Jan. 26 festival is not entirely festive.

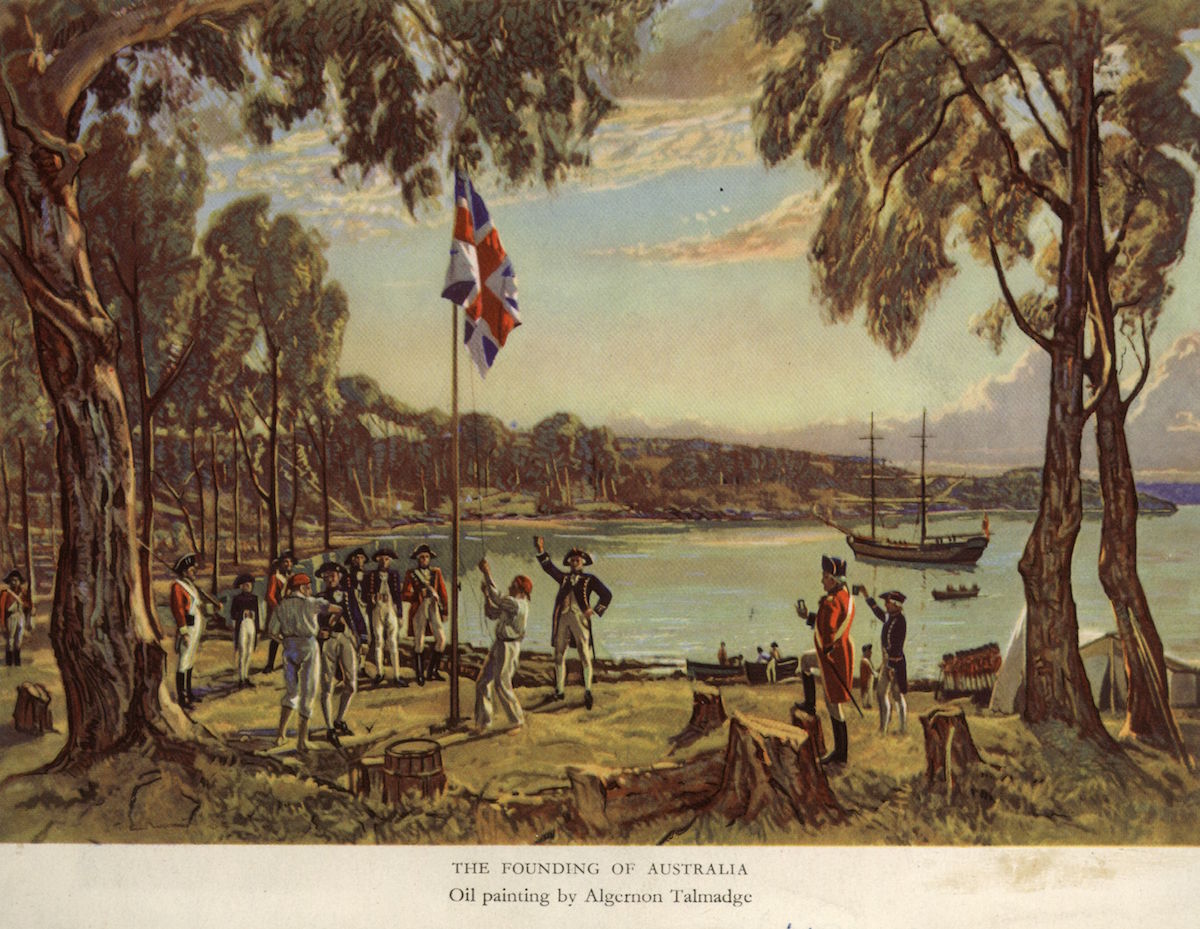

The most basic reason why the national holiday falls when it does, as explained by the National Australia Day Council, is that it marks the day in 1788 when the so-called “Father of Australia,” Captain Arthur Phillip, and his “First Fleet” of 11 ships arrived at Sydney Cove and raised the Union Jack. They thus staked out Britain’s claim to the eastern half of the continent that had been claimed by Captain James Cook about two decades earlier, and Phillip became the first governor of the New South Wales territory.

Those ships, however, were carrying convicts, who turned Australia into essentially the world’s largest prison. Experts say that, in some ways, that’s America’s fault.

In the late 1700s, Britain was in the early stages of an industrial and agricultural revolution. As consumer culture grew, so did the wealth gap and the rate of property crime (e.g. theft). When British jails filled up, a handy solution was to send prisoners to the colonies in North America. Convicts were seen as a potential labor pool.

“The government effectively passed control of convicts to contractors responsible for shipping them over to North America, and once the shipping companies took them to North America, they effectively sold them off to private employers, who could use them for the [duration of their] sentence—a kind of indentured labor,” says Francis Bongiorno, a historian at Australian National University.

Then the American Revolution happened, and the old destination would no longer work. Looking for another place to house those convicts, they turned to Australia. That solution that would be used for many decades, until the last convicts transported went to Western Australia in 1867. Bongiorno says convicts, owned by the government, worked for the government in Australia building roads or were passed onto private employers who would manage their meals, housing and discipline. Many convicts ended up working on sheep farms.

And, though states and territories began marking Australia Day in 1935, it wasn’t until 1994 that Australians began to celebrate Australia Day consistently as a public holiday on Jan. 26. After all, not all Australians have been proud of the country’s past as a penal colony.

“Until the 1970s Australians who had a convict ancestor kept quiet about it,” says Douglas Craig, another historian at the Australian National University, who says that such family trees were said to bear “the convict stain.”

And that period in history is controversial for another reason, too.

Phillip is generally seen to have taken a progressive stance toward relations with the aboriginal people—despite a famous incident during which he was stabbed during a dispute—during his four years as Governor, a time during which the colony was constantly running short of supplies. But the coming of large numbers of British convicts nevertheless heralded a long period of much suffering for the people they displaced. For example, the arrival of those convicts preceded a smallpox outbreak that experts say had a disastrous effect on the indigenous population.

Bongiorno says academic discussions about Australia Day are similar to those often held about Columbus Day in the U.S.: “It’s not a terribly important event in a way, and a double-edged kind of national day. It’s something that people enjoy celebrating, it’s in the summer, the period before children go back to school. Yet it’s obviously commemorating an act of dispossession and British settlement, the taking of land, a history of tragedy. Australia sees itself as multicultural, but [the holiday] commemorates an old Australia.”

Such tensions between British Australia and the more modern, multicultural Australian society persist around the holiday. For example, a billboard depicting two girls in hijabs waving the country’s flag on Australia Day 2016 at Docklands in Melbourne was taken down by a vandal. Australians launched a $200,000 crowd-funding campaign to raise money for a new one.

As for the nation’s history as a place for convicts, however, the modern Australia is showing signs of shedding its embarrassment, says Craig. Old ideas that an ancestor’s criminality could be inherited had faded away, while nationalism increased as Australians’ identities became less intertwined with that of the British Empire. In the last four or five decades, people have begun to realize that this particular slice of Australia’s past—the part commemorated by Australia Day—could be the basis for a “powerful national myth.”

“A nation founded by criminals—literally the refuse of Britain—became one of richest and most law-abiding nations on Earth,” he says. “They should have been proud.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com