Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME, to see how it all comes together. Catch up on last week’s installment here.

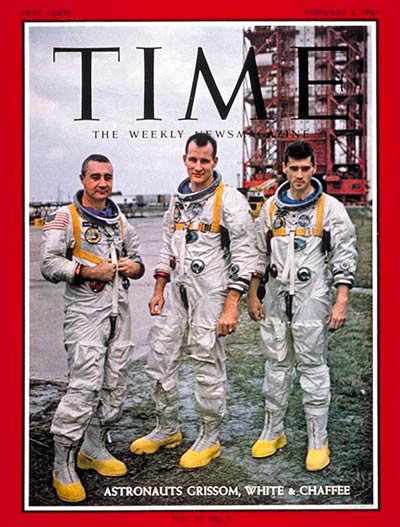

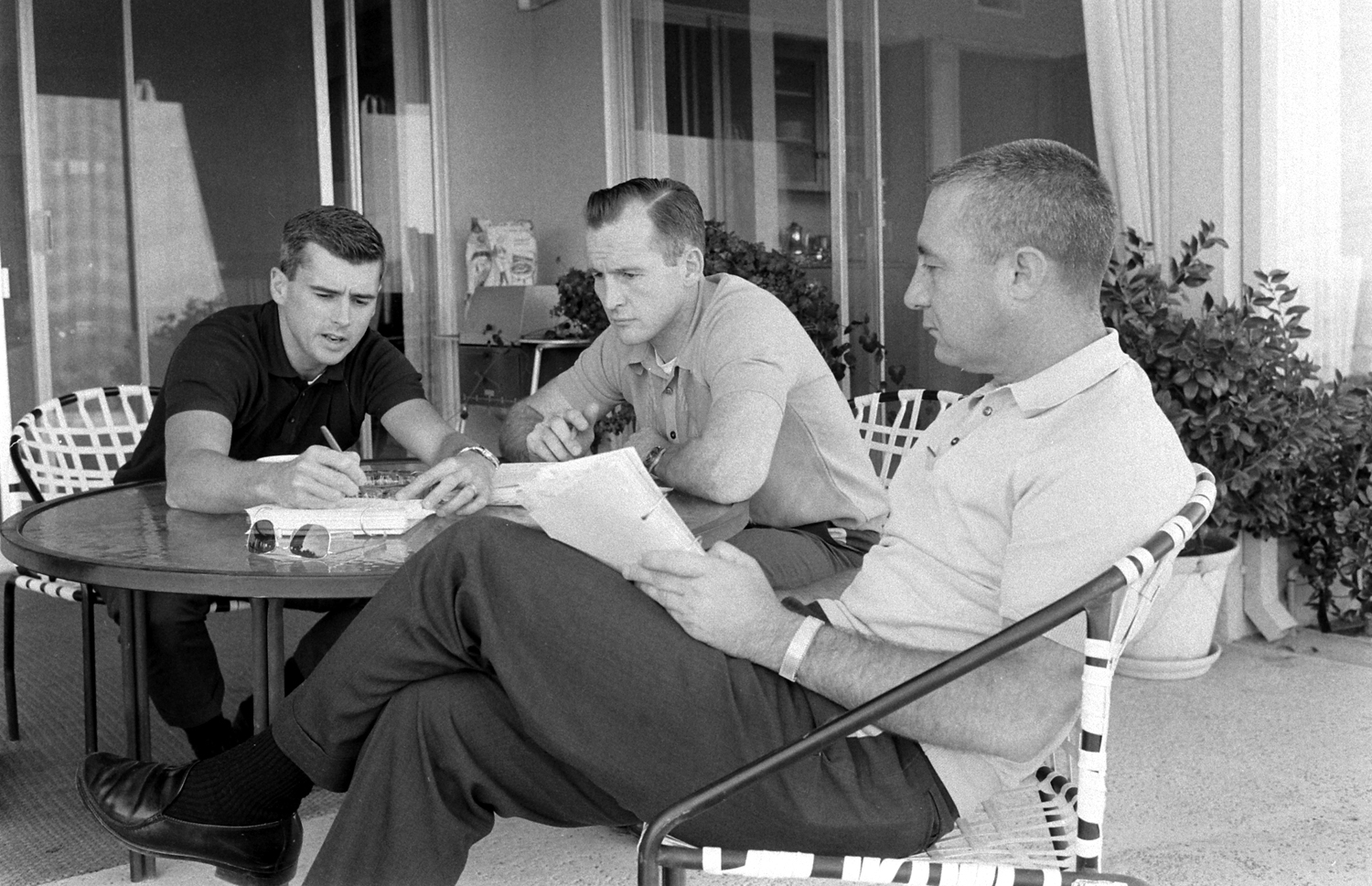

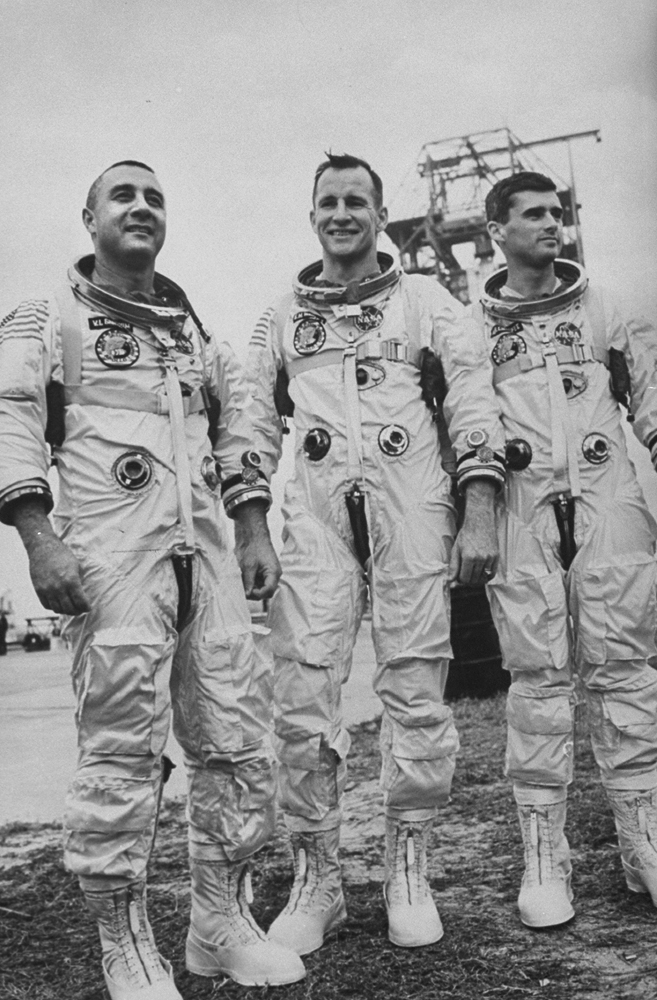

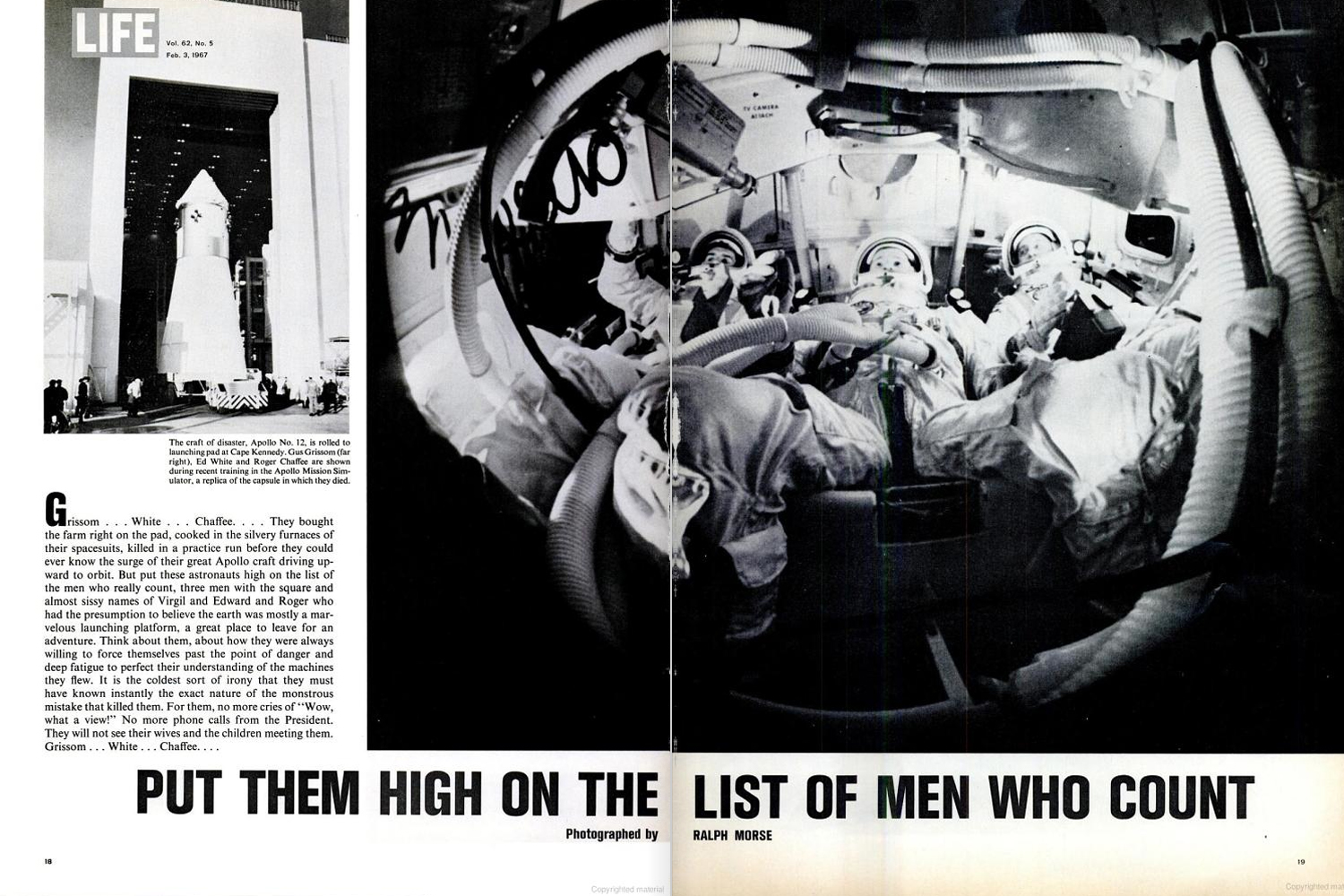

The cover on this issue betrays little about what the lead story relates: three astronauts stand calmly, partially in uniform, looking like they might be on their way to the moon but they also might be on their way to fix a car.

The story, however, is anything but calm. The three astronauts had been killed, on Jan. 27, in a routine test. The mission was later designated Apollo 1. But, as TIME explained, the everyday image of the men at work was appropriate for the tragic irony of the accident:

Death could have come in any number of bizarre ways. In the explosion of an errant rocket in the view of millions on TV; in the instant incineration of a capsule out of control during the treacherous reentry into the earth’s heavy atmosphere; in the coffin of a malfunctioning craft unable to descend that orbits, orbits, orbits in the spatial void while power ebbs and life leaks away in slow suffocation.

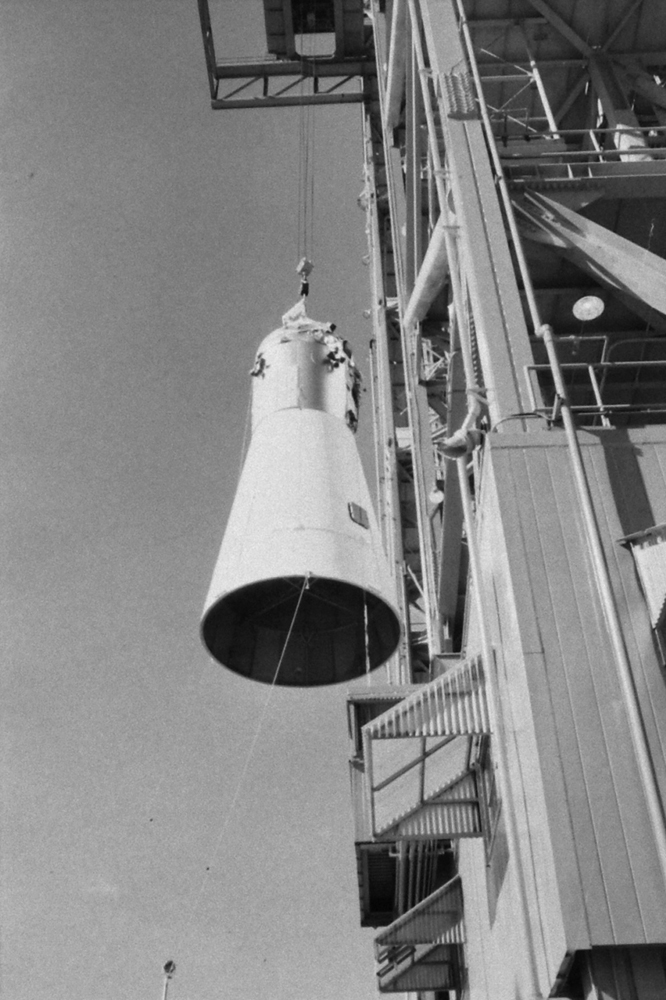

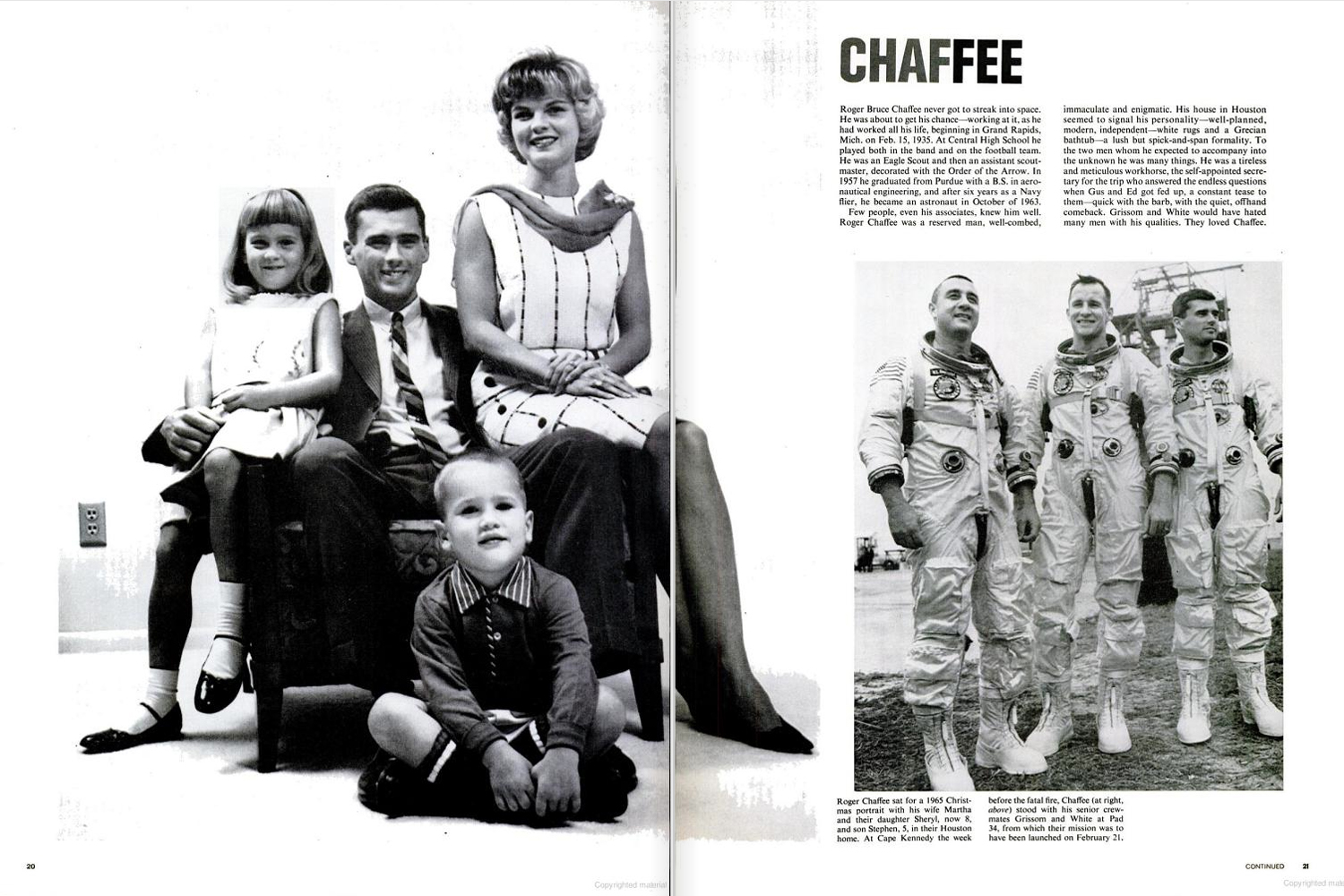

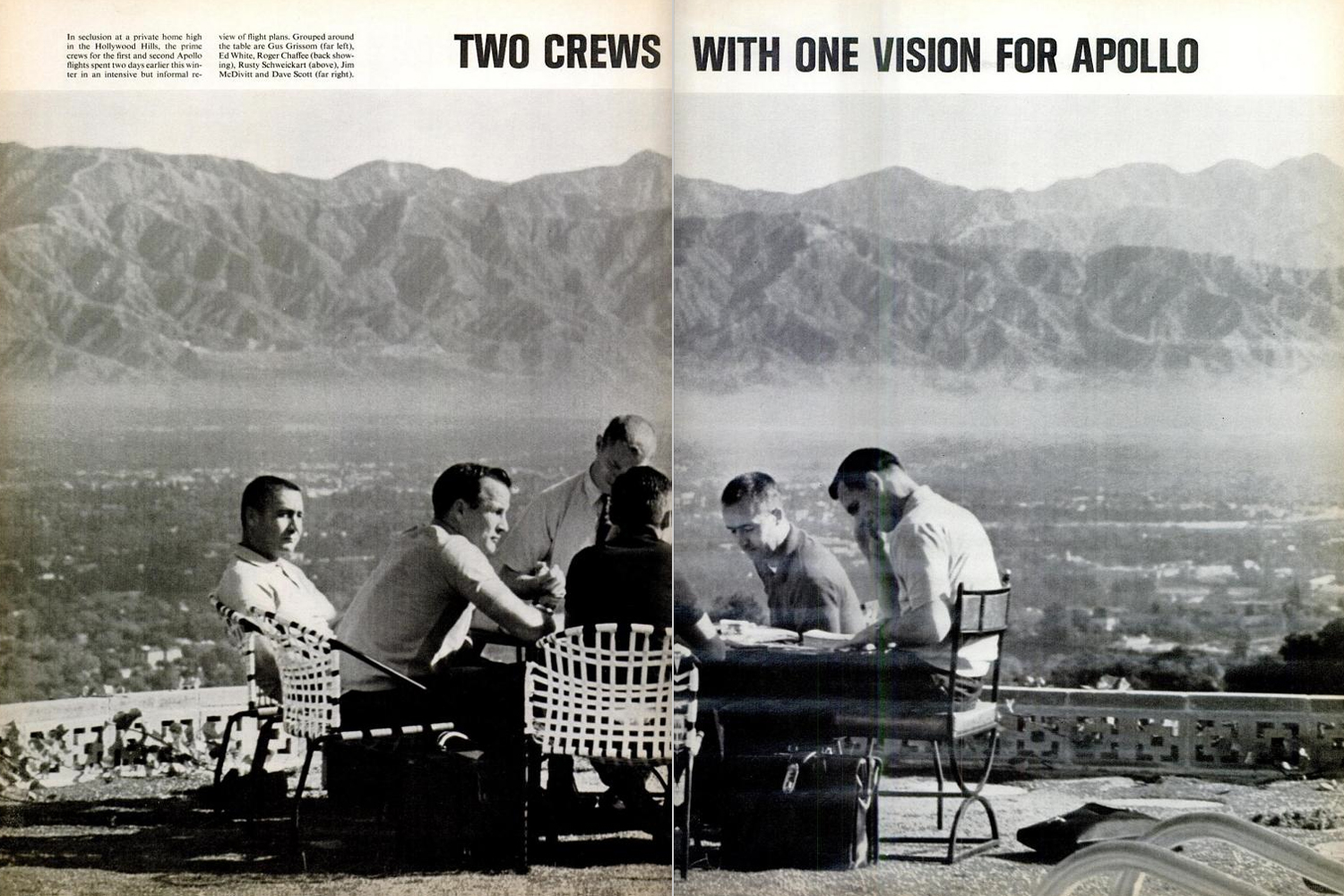

But the first three U.S. astronauts to die on duty were motionless and earth-bound when they were killed last week. With helmet faceplates closed and suits pressurized, they reclined in a row on padded couches in their cylindrical Apollo capsule, running through the countdown of a simulated launch, a routine but rigorous rehearsal for the real thing. They had been there 5 hrs. 31 min. when fire exploded in the cabin. Within seconds, Lieut. Colonel Virgil Grissom, 40, Lieut. Colonel Edward White, 36, and Lieut. Commander Roger Chaffee, 31, lay dead in the charred cockpit of a vehicle that was built to hit the moon 239,000 miles away, but never got closer than the tip of a Saturn rocket, 218 ft. above Launching Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy.

The magazine portrayed the deaths as a reminder that, even after more than a dozen successful space missions—including landmark missions by Grissom and White—what was going on at NASA was both highly dangerous and highly technical. As the National Air and Space Museum explains, a number of things had gone wrong that morning, and when the electrical fire began the men were unable to execute their escape procedure before they were overcome by the smoke and fire. (You can read more about what happened here.)

The deaths would raise the perpetual question when it came to space exploration: was the risk worth the rewards? One answer to that question, TIME noted, had been supplied by Gus Grissom himself, who had spoken on the topic before his untimely death.

“If we die, we want people to accept it,” he had said. “We are in a risky business, and we hope that if anything happens to us it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life.””

The Apollo 1 Launchpad Fire: Remembering Grissom, White and Chaffee

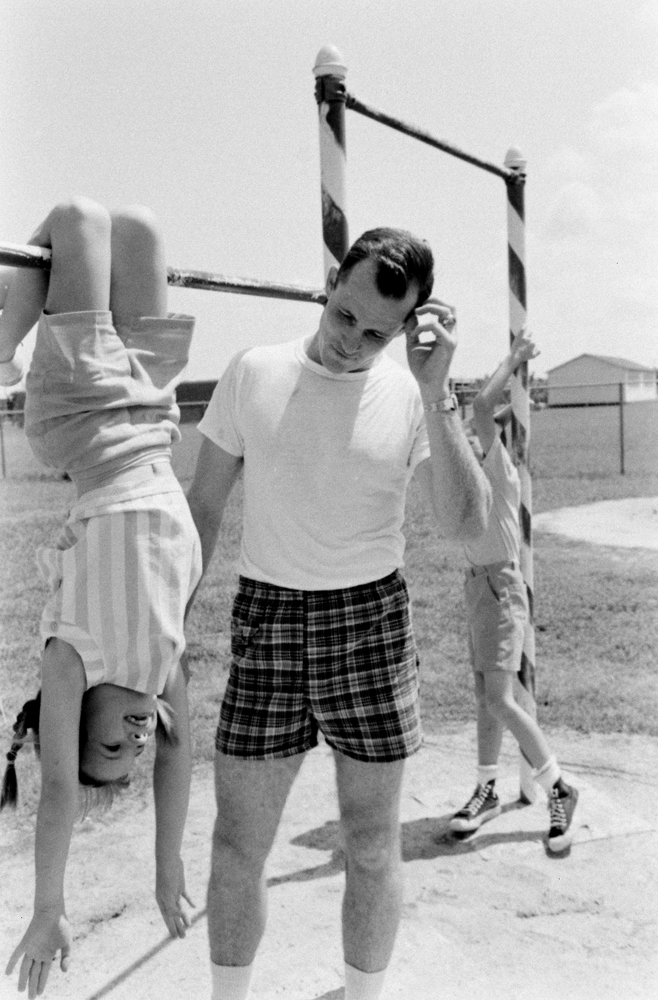

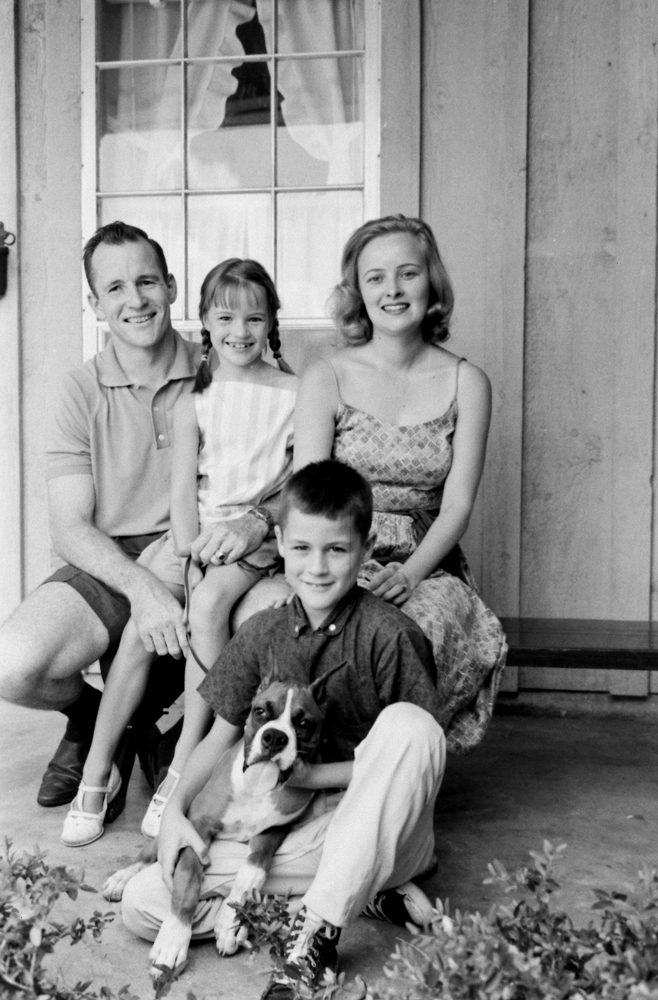

![114618284.jpg Home a hero after his successful 1965 mission in Gemini 3, [Gus Grissom] greeted his parents who came from Mitchell, Ind. for the flight.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/140123-apollo-1-grissom-white-chaffee-17.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Prescient reaction: The letters page contained a message from an engineer living in Binghamton, N.Y., who had read the previous week’s cover story about air pollution and proposed an idea that might help—something that may sound familiar to drivers of today’s hybrid cars. “One answer would be a vehicle combining a conventional internal combustion engine and an electric engine with batteries,” the engineer wrote.

A first: The death of James H. Bedford, a California psychology professor, was an unusual milestone for science. Bedford, who died of cancer, was the first person to have his body preserved by the Cryonics Society of California in case revival was later possible after a cure for cancer was discovered.

Some things do change: A story in the world news section relayed word that British Prime Minister Harold Wilson had met with Charles de Gaulle to try to convince the French President to allow Britain to enter the European Common Market, which France had previously vetoed. With the British pound in a delicate state, citizens were eager to join the other six nations of the Common Market, an event that finally took place about six years later. The Common Market would later become an element of the European Union—which Britons voted in 2016 to leave.

Strange vintage ad: This one isn’t notable for any particular old-timey sentiment or design, but the wording still stands out, assuring business owners that “now your employees don’t have to die” to benefit from insurance.

Coming up next week: A cover story about Japan

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com