The idea started with women on Facebook. On the night of Donald Trump’s surprise victory in November, a grandmother in Hawaii named Teresa Shook went online and called for women to storm the capital on Inauguration weekend.

“At the same time, 5,000 miles away, I was doing the same thing,” explains Bob Bland, a female manufacturing entrepreneur in New York City. “Within an hour we’d found each other, merged our events, and we were off to the races.” By the next morning, thousands of people from across the U.S. had signed up to join what could become the Women’s March on Washington.

Bland quickly realized that in order to transform the march from an angry Facebook group into a progressive coalition, she’d need help. She enlisted veteran organizers Tamika Mallory, Carmen Perez and Linda Sarsour as national co-chairs with the aim of wrangling one of the largest Inauguration demonstrations in -history—and making it one that brought together activists of all stripes.

“In the past, progressive groups have been working sort of in isolation,” says Mallory, a New York City—based civil rights and anti-gun—violence advocate. “People didn’t really have the time and bandwidth to understand other folks’ issues.”

By the week before the Inauguration, more than 600 marches nationwide and around the world had been planned in solidarity. And while the Women’s March drew support from likely allies such as Planned Parenthood, NARAL Pro-Choice America and the Global Fund for Women, hundreds of other organizations have also signed on as partners, like the Natural Resources Defense Council, the NAACP, the environmental advocacy group 350.org, the health-care–worker union 1199SEIU and the Council on American-Islamic Relations, among others.

Leaders of these progressive groups agree that in a Trump-run America, the future of their movements will hinge on the idea that these groups can and will throw their weight behind causes that may not be their own.

“People are expecting us to show up at a march and talk about our bodies and our reproductive rights,” says co-chair Sarsour, executive director of the Arab American Association of New York. Instead, she says, “we’re bringing together all the progressive movements.”

The march is the first major effort by the progressive movement to get back onto its feet after having lost control of any branch of government. For many of its leaders, the road to reclaiming Congress and the White House will be filled with demonstrations far beyond Inaugural weekend. Civic involvement, Barack Obama argued in his final speech in office, is “what our democracy demands.”

But the barriers to success are high. A grassroots upswell on the right energized the Republican Party during the Obama years, and eventually toppled some of the party’s leaders. It’s yet to be seen if progressives will unite the same way.

At the same time, the leaders of the march were quick to insist that it was not conceived only as an anti-Trump protest, even though flooding the capital with protesters on the day after the Inauguration was sure to send that message. Instead, they say, it was meant to be a public declaration of a new coalition, united to protect the rights of women, minorities and anybody else who feels they will be made vulnerable by the policies and politics of a Trump presidency.

As the activist and pundit Van Jones puts it, “Trump is the best organizer of progressives that we’ve ever seen.”

Of course, no one knows what this coalition looks like moving forward. These groups have historically had vastly different agendas, used different tactics and haven’t even always gotten along, and it remains to be seen if they’ll work together after the historic march, and if they do, what that would even look like. Internal conflicts over race and class may plague the new progressive movement just as much as they’ve hobbled the Democratic Party. “Those linked arms are going to have some sharp elbows,” Jones says.

Indeed, the test for the anti-Trump movement will be whether these historically distinct groups of progressives will continue to cooperate over time. “Just because you have a rushing river of energy and interest doesn’t mean you can turn it into a hydro-electric dam to build real power,” says Jones.

For now at least, there’s a consensus among progressives that any response to Trump must present a unified front. “Every single aspect of this is being worked on with a much broader set of allies than we’ve worked with in the past,” says May Boeve, executive director of the environmental group 350.org. “[Trump’s] politics are about division, so our best tool to confront it is unity.”

Some leaders say that’s needed now more than ever—that the progressive coalition that gathered behind Barack Obama was more illusion than real cooperation. “There was an assumption that you had an extraordinary movement when in fact you had an extraordinary candidate,” says NAACP president Cornell William Brooks. “We did not inaugurate the progressive movement.”

The risks to unity are as numerous as the crannies of federal politics. Trump or Hill Republicans might offer one group just enough on a favorite issue to win a measure of judicious silence. Four years is a long time to hang together.

Some solidarity also arrived from outliers on the right. Evan McMullin, the conservative third-party candidate who challenged Trump, was ambivalent about the march but was encouraged by the idea that constitutional conservatives could have more in common with liberals than ever before. “People on the right and the left want to defend the Constitution,” he says.

John Elwood, an evangelical Christian who co-founded the Christian environmental group Climate Care-takers, says he’s devoted to the “sanctity of life” in its fullest interpretations but will march alongside abortion–rights activists anyway to bring attention to other -issues—-especially climate change.

“I’ll focus on the areas that I have in common with the marginalized community,” he says, “not on the distinctions that would separate us.”

Some organizers also plan to co-opt 2010 Tea Party tactics to sway politics on the state and local levels, staging sit-ins and phone blitzes, and causing a ruckus at as many public events as they can. “This is one of the silver linings in a very dark cloud,” says Ezra Levin, a former congressional aide and co-founder of the Indivisible Guide, an instruction manual on how to use Tea Party tactics to disrupt a Republican–controlled Congress. The manual has been viewed more than 4 million times since the election.

“There is this huge amount of energy that is out there to resist Trump,” says Levin. “And it’s being led by these local leaders.”

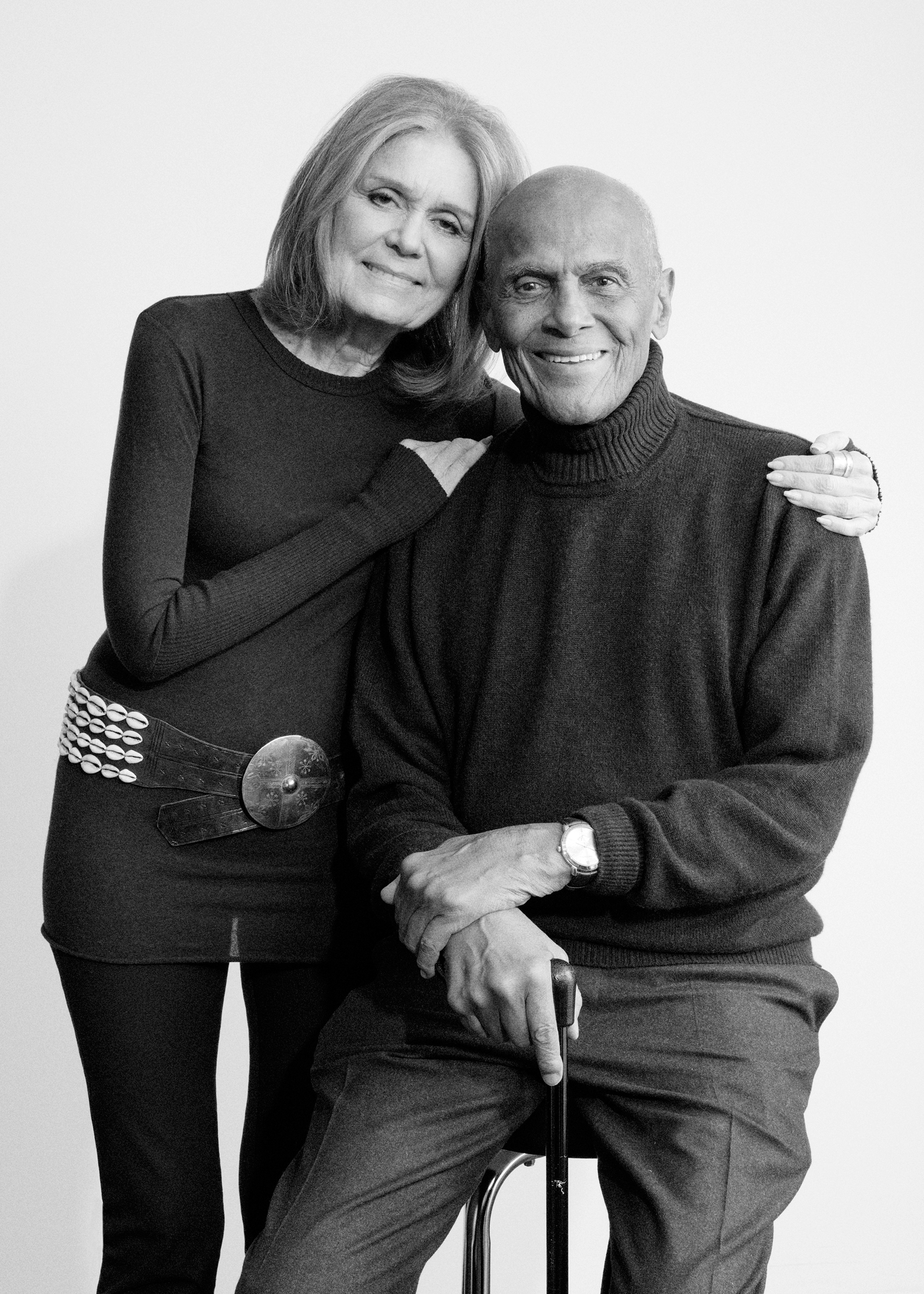

There’s no guarantee—there never is with activism—that the progressive coalition will have a lasting effect on Trump’s plans. But with Republicans in control of the House and Senate, some group leaders are hoping to make an impact, even if they’re not expecting a whole lot more just yet. But veteran activists see hope in a progressive movement that has more people and energy than what they saw in the 1960s or 1970s. “This is unprecedented in my life,” says Gloria Steinem, a leader of the original women’s-lib movement and one of the march’s honorary co-chairs.

And so the masses will take to the streets. Only they know how long they’ll stay.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com