We are approaching a time of great threat, but also a time of great potential.

As academics devoting our lives to the pursuit of increased knowledge and access to education in service of society, we stand watch. This political season has legitimized racist, misogynist, homophobic, transphobic, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, xenophobic and ableist attitudes. This is no small thing. The threat is clear, and as a diverse group of women, we understand the threat is to our bodies, our minds, our communities and our planet.

We see what is at stake in the halls of education. On our campuses, we have seen the rise of hate speech and hate crimes. We watch warily the threats of policing of scholarship, so reminiscent of McCarthy-era scare tactics (see the “Professor Watchlist”). We witness first hand the fear — of registries, of deportation, of violence — of so many of our students and colleagues.

We also see the clear threat to the achievements of anti-oppression protesters, activists and movements that strive to build a more perfect union. As students and teachers of history, political science, anthropology, humanities, sociology, social work, science and economics, we call attention to the disturbing historical patterns that threaten the foundations of our democracy. We watch as the social contract that has bound us together as a nation of immigrants begins to fray. We are concerned with the rise in inequality and the inevitable social instability that accompanies it. We grieve the terrifying refusal to acknowledge facts as truth.

In light of these threats, we will not stand silent. We stand in support of the upcoming Women’s March — in Washington, in all 50 states, and in more than 50 countries around the world. We stand for the march as a form of resistance, and as a form of movement making.

Said Coretta Scott King: “Women, if the soul of the nation is to be saved, I believe that you must become its soul.” With King we believe that women — broadly conceived — are positioned to fight not only for ourselves, but also for every individual in the nation who suffers under systemic oppression. The legacy of women’s rights has proven that women have not just the voice, but also the power, to dismantle systems of injustice.

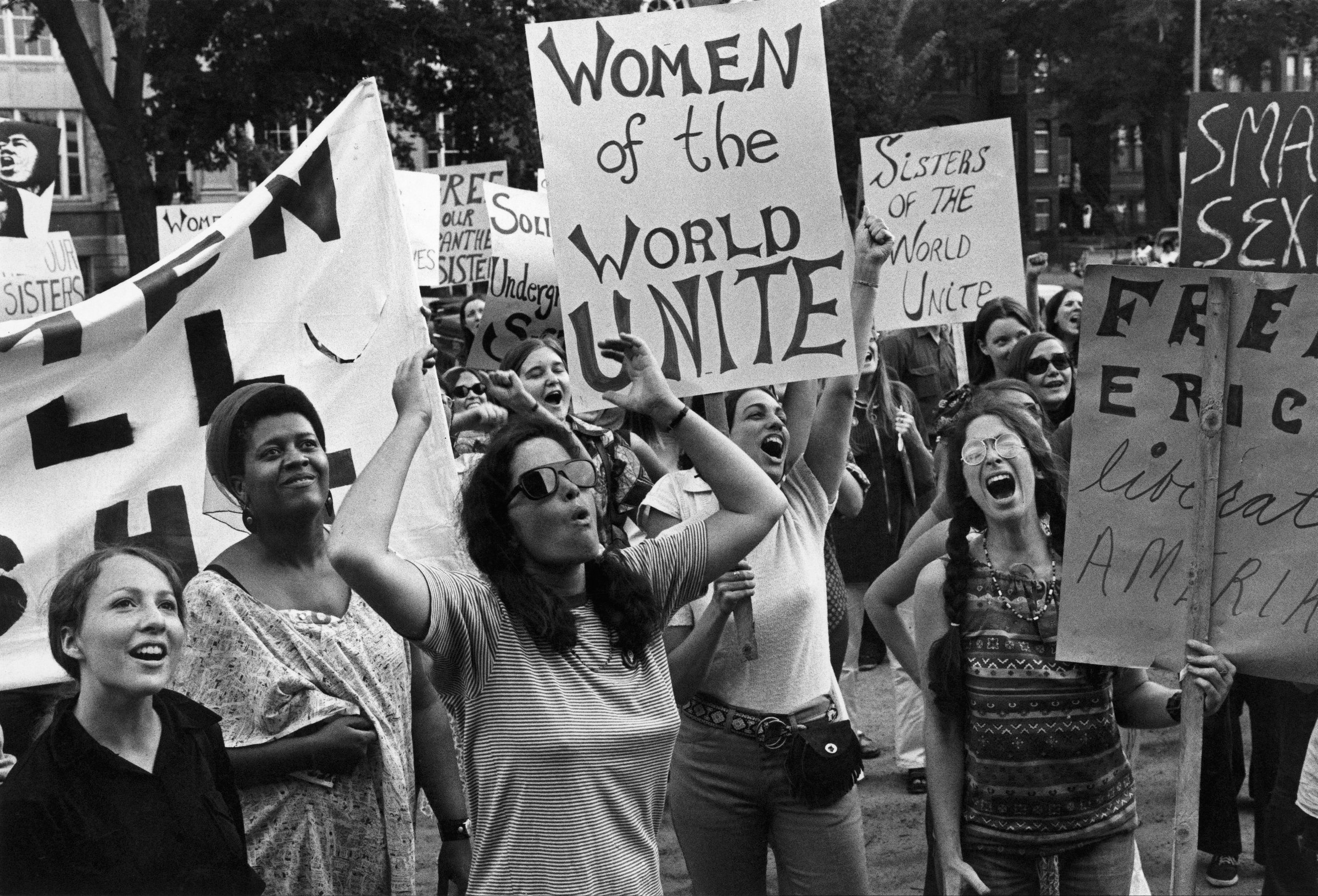

But now more than ever we must recall how unjust exclusions in our movements, symbolized in the history of previous Women’s Marches, persist to this day. In the early 1900s, Women’s Marches demanding voting rights, such as the Woman Suffrage Procession in 1913, segregated black marchers, relegating them to the back of the file. A 1970 Women’s March, known as the women’s “Strike” for equality drew 50,000 women in New York and more than 100,000 women in other cities. Looking back on that moment, many have argued that white feminists’ efforts to be liberated from the home failed to consider fully how the unrecognized domestic labor of working women and minority women allowed their own liberation.

The 2017 Women’s Marches and resulting movements must commit to intersectional feminist organizing, activism and resistance with frameworks meant to empower women of all races, cultures, religions, abilities and sexual identities. An “intersectional” approach means that we must center our new movement on the working class women and women of color, on the women who face low pay, wage gaps, lack of parental leave and affordable childcare, as well as embarrassingly poor access to healthcare, housing and family planning services.

American women have never been wholly white, nor has the working class ever been simply a broad swath of white male breadwinners working in manufacturing or industry. Just last year, there were 820,000 home health aides, most women of color, and only 64,000 steelworkers in the United States. And we would do well to remember that not every woman can “lean in.” Both the “lean in” discourse and those narrow definitions of the working class make so much of women’s work invisible, scrubbing it of social and political value. Working class, minority and marginalized women are central to the advancement of feminism. Questions of women’s rights are a matter of justice — and survival — not just for these groups, but also for the country as a whole.

This is the moment to rise up and to finally rise to the challenge of remedying past exclusions and blind spots, no matter how uncomfortable and painful. We need good jobs. We need equal pay. We need affordable healthcare. We need excellent schools. We need egalitarian households. We need our family members safe and at home.

We know that intersectionality makes us stronger — take the Fight for $15, or the diverse group that led to the defeat of State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez in Chicago. We are on the brink, but we are well poised.

As educators and activists, we have an obligation to use this moment as a teachable one. Remembering the many and momentous times women have come together to articulate a better vision for the United States, and hoping to rectify the exclusions of the past, we stand with the Women’s March. The soul of the nation depends on it.

Adom Getachew is Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago and Dawn Langan Teele is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania. They’ve signed this op-ed along with 950 other academics and counting.

MOTTO hosts provocative voices and influencers from various spheres. We welcome outside contributions. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of our editors.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com