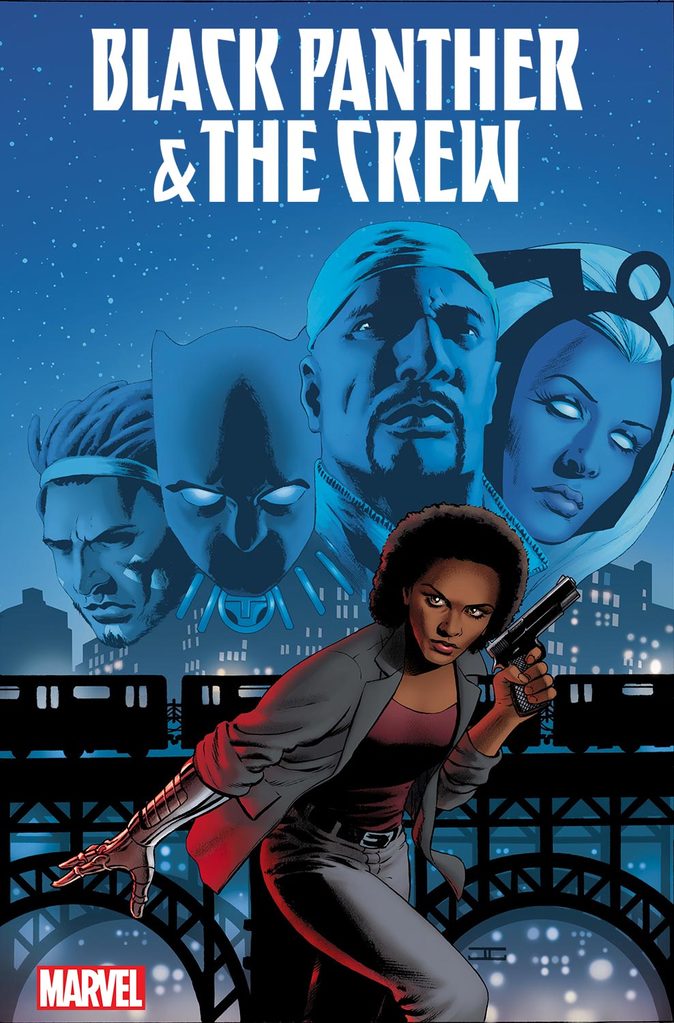

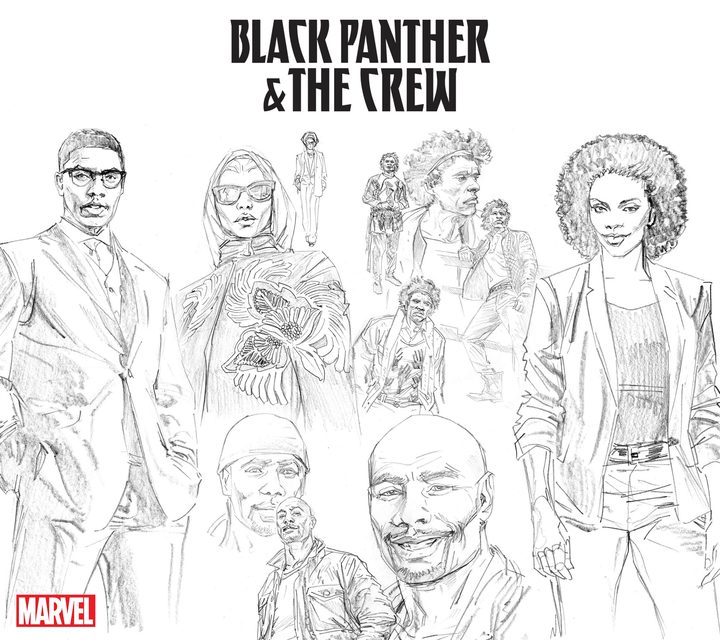

Black Panther’s world keeps getting bigger thanks to writer Ta-Nehisi Coates. After taking on the Black Panther series in 2016 and collaborating with writer Roxane Gay and poet Yona Harvey on a spinoff, World of Wakanda, Coates is adding another comic book series: Black Panther & The Crew. It’s a revival of an earlier series by Marvel’s first black editor Christopher Priest but with a new set of characters. Coates will team again with Harvey to tell the story of a team of heroes—Black Panther, Storm, Luke Cage, Misty Knight and Manifold—set in Harlem.

Coates, a National Book Award and MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grant winner, became the most famous comic book writer in the non-comic-book-reading world last year when he took on the Marvel character. The storied publisher recruited him to revive Black Panther, the first black superhero in mainstream comic books. Black Panther, whose given name is T’Challa, is the ruler of the technologically advanced African nation of Wakanda, a scientist and an Avenger. Coates’ 2016 version begins with a rebellion against Wakanda’s monarchy. The first issue sold more than 300,000 copies.

Marvel has tried to widen its perspective from that of the white male creator in recent years with changes to its characters and, more slowly, its writers and artists. Priest’s version of The Crew has been called by critics “the blackest superhero story that Marvel Comics ever published” and dealt with issues like gentrification, poverty, religion and crime. Coates and Harvey’s version endeavors to be similarly ambitious.

TIME spoke Coates and Harvey about the new series; a lightly edited transcript follows:

Why did you decide to do a spin-off about The Crew?

Coates: Christopher Priest wrote what turned out to be a mini-series that I just adored called The Crew. Black Panther wasn’t in the original Crew, but he was weirdly sort of related because an ancillary character of his series was in the Crew. It was a unique book because the majority of the characters were black. So when I came back to write Black Panther, I read a bunch of Christopher Priest’s stuff, and I wanted to bring it back.

I was going to try to do it with the same members that he had. But it became clear that certain characters would not be available for various reasons. So I decided to think about it in a different way and think about something new.

What else is new about it besides the characters compared to the old version?

Coates: The old version was a great crime story. And you’ll see elements of that in this, but there’s a Cold War aspect too. I’m new to this so I’m trying to not blow the story, but at the same time try to let people know what it is.

I feel your pain.

Coates: You see the events of today. There are also flashbacks to events of the Cold War. It all connects. The basic idea is each of these people for various reasons has a conflicted relationship with the neighborhood, Harlem.

There’s this concept in comic books of street characters—characters who mostly deal with street-level stories—those are your Daredevils, your Luke Cages, things that are considered lower-tier. And then you have your more cosmic level heroes, like The X-Men, the Fantastic Four, Avengers, that sort of thing. What we have in this book is a group of characters that operate on both levels. What does it mean to protect the street and protect the world? How are those things connected? What happens when T’Challa is walking down the street without his [Black Panther] uniform and people don’t recognize him, he’s just a black person? Same with Storm.

I don’t want to lean on that too hard and make you think there’s too much page space thinking about this, but it’s baked into the book.

The inciting incident of this story is an activist dies in police custody, and there’s an investigation. Why did you decide to use that as the jumping off point?

Coates: This is in the air. It’s not like I looked at a Black Lives Matter protest and was like, “Hey, I want to write a comic about that.” But you’re confronted with it every day. So when I sat down to think about what is this story with four black protagonists about, and you start scribbling, that rises up. The events of the day are with me. It seemed like an opportunity to do something. It becomes clear in the first issue that the activist is not just an activist. There’s something more going on there.

How much do you think the events of the day being on your mind are because you are also a writer, a journalist, who is writing about social justice issues and race or interviewing President Obama?

Coates: Those things don’t influence each other as much as you would think. These issues are all over comic books and particularly throughout the history of Marvel. What weighs on me is reading X-Men as a child. Those books influenced me so much. They were charged, they dealt with discrimination, they dealt with being an outsider. They dealt with the things that I was feeling.

The comics I’ve always read, have always had a philosophical thread. So when it came time for me to write comics, I just felt like that had to be. It’s definitely in the Black Panther books now. It’s not just a story about a king that’s trying to rule. I’m trying to answer other questions, philosophical questions, social questions.

Black Panther dealt very directly with questions of sexism, female empowerment and queerness, especially when it came to Black Panther’s all-female guard.

Coates: [In some of the earlier versions, the guards] are like 16 years old. It’s weird. I want to say that was a different time, but it was only 15 years ago. I think now, you have an all-female guard, you can’t just look at them strictly from the perspective of the teenage, male comic book reader. Like, when depicting a same-sex relationship, I was really careful. You don’t want it to be a performance [for the reader.] You want the characters to own it. I don’t know that we would have been having these conversations 15 years ago. It’s good they’re happening now.

To that point, you’ve said before that those plots were in part a response to a conversation online about the ways in which comic books failed to represent complex, powerful women. Now that you’ve written a whole series, do you continue to pay attention to the online debate about representation and feminism?

Coates: I hope so. Yes, I am. You know, there were no women in the original Crew. And it just felt like you could not have a book like this without women. The moment it became clear I couldn’t do the original Crew, and I had to come up with my own, it just felt wrong to put together five dudes. These days, that’s not going to fly. So in its very conception, yes.

I have to admit I’m not familiar with the original run of The Crew, was that set in Harlem as well?

Coates: No. It was set in a fictional neighborhood called Little Mogadishu in Brooklyn.

So why Harlem?

Coates: Because I lived in Harlem for like seven years, and I love the neighborhood. There’s some history there for Marvel, too. I think Storm’s dad was from Harlem or lived in Harlem. Misty Knight and Luke Cage have connections there.

What’s the difference in writing about a place you’ve actually lived in and writing about a country that doesn’t exist?

Coates: I could actually see the blocks. There’s an opening scene that happens on 125th and Lenox Avenue, and I could see it all right in front of me. There are jokes I could make about changes in the neighborhood that I just knew from being there.

How much did you think about the history of sexism in comic books before you started writing?

Harvey: Are the things that trouble women the things we see depicted in culture? Do we walk out the door terrified of mugged or attacked? I was thinking about these strong female characters, and how can I bring more subtlety or nuance to that idea. I think maybe for men when they write about women they’re imagining this anxiety about the worst thing that can happen to as part of [the character.] But I don’t think we step out of the house thinking we’re in trouble or need to be rescued.

What are the challenges of dealing with racial issues in this format?

Harvey: I think it’s a good challenge because it gives people a touchstone for the current moment, but there’s still this imaginative space where the story can unfold. There’s a nice tension between those two things, the real and the fantastical.

How has your poetry affected your work in comic books?

Harvey: For the first project I kept resisting. I thought being a poet was a negative somehow. But then I had to embrace what poets do, examine tiny details and draw out a larger story. And it helps with the language and the voice of the characters. I have this little trick where I imagine the poetic voice of the character, whether it’s very terse or romantic or sensitive.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com