Gene Cernan never knew about the plan NASA approved to cut him loose in space — or at least he didn’t know about it at the time. When Cernan, who died today at age 82, did learn about it, long after any danger had passed, he could only laugh. It didn’t matter what NASA’s secret plans were, he’d have flown anyway.

It was in June 1966, as he and Tom Stafford were heading to the launch pad to take off aboard Gemini 9, that Stafford — but not Cernan — learned of the plan. Stafford was the commander of the mission — the man who would sit in the left-hand seat of the spacecraft. Cernan was the second in command of the two-man crew, but his subordinate position carried one important perk: the man in the right-hand seat was the one who would perform any spacewalks, while the commander stayed inside and tended to the ship.

Spacewalks, however — then and forever — were dangerous things. There was no certainty that an astronaut who ventured outside a Gemini spacecraft would be able to climb back inside again — all manner of problems from a breakdown in life-support systems to a snaring of the long umbilical cord connecting him to the ship potentially making it impossible. So, shortly before the two men rode the gantry elevator to the top of the rocket on launch day, Deke Slayton, the chief astronaut, pulled Stafford aside and told him that in an emergency like that, he was to do everything he could to save his crew mate, but if it all failed, he was to cut him loose, seal the hatch and fly home alone. In the cold mortal math of space travel, it was better to lose one man than two.

Cernan would survive that mission, his first, but danger seemed to shadow his space career. He came to describe his time outside the Gemini IX spacecraft as “the spacewalk from hell” as his visor fogged up, his suit overheated, and he and NASA learned together how difficult it is for a free-floating astronaut to maneuver in the screwy physics of zero-g. Three years later, he and Stafford, flying together again on Apollo 10, would nearly meet their ends as their lunar module spun out of control less than nine miles above the surface of the moon during a mission that was the final dress rehearsal for the Apollo 11 lunar landing.

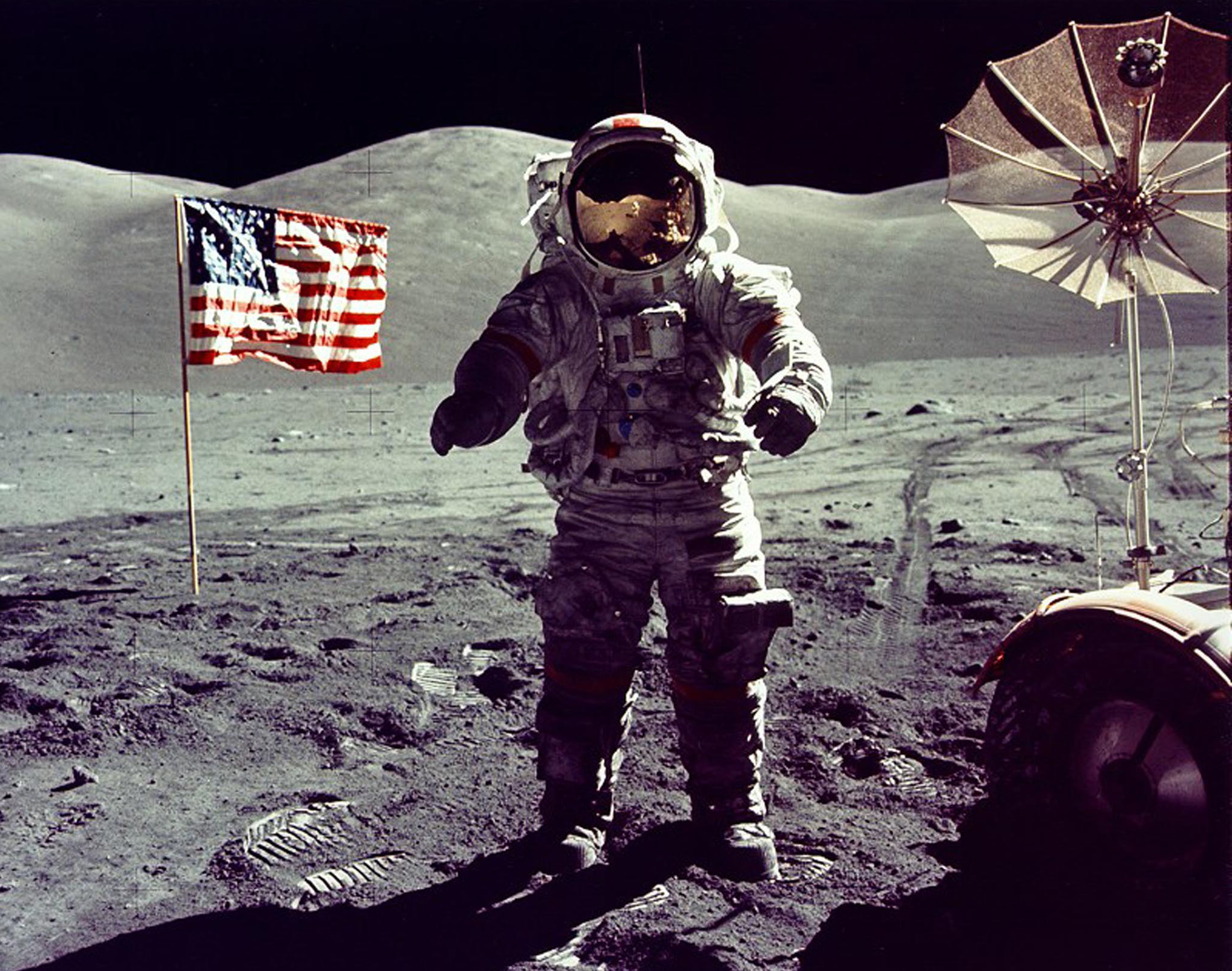

It was only as commander of Apollo 17 in 1972, the very last lunar landing, that Cernan would enjoy the perfect mission, spending three days exploring the surface of the moon with crew mate Jack Schmitt. As the ranking officer of that final crew, Cernan had the prerogative of sending Schmitt up the ladder of the lunar lander first when they ended the third of their three long moonwalks, at just before 5:54 p.m. E.T. on Dec. 14, 1972. Cernan, left alone on the surface, spoke for himself, his crew and, he hoped — perhaps naively, perhaps not — humanity as a whole.

“As I take man’s last step from the surface … I’d like to just say what I believe history will record: That America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return: with peace and hope for all mankind.”

The final footprints he left in the lunar soil before stepping onto the ladder turned 44 years old a few weeks ago. It is a mark of America’s loss of cosmic daring that they remain the freshest of all of the many prints NASA astronauts made during the course of six landings. Still, while Cernan often spoke disappointedly of America’s abandonment of the lunar frontier, he remained an optimistic, even ebullient man.

He confessed to only a few regrets in his 80-plus years of life: a U.S. Naval aviator, he struggled to come to grips with the fact that so many of the men he trained with went off to fight the Vietnam War while he got the glory duty of flying to the moon.

Other astronauts accepted NASA’s argument — a fair one — that the space program was a very real part of the Cold War and the astronauts were the foot soldiers. Not Cernan. “That was my war,” he said of Vietnam, in the 2007 documentary In the Shadow of the Moon. He never quite squared it with himself that he didn’t fight it.

He regretted too — a little — not appreciating his moments on the moon when he had them. In 2010, I was watching some of the moonwalk footage with him — particularly the clip of him and Schmitt singing and joking as they bounded along the surface — and he recalled the countless hours he and his crew mates spent training in simulators before missions.

“I wish I could have pushed a pause button during those moonwalks the way we could in sims,” he said. “They just went by too fast.”

It was with children that Cernan seemed to take his greatest joy in the decades of life he got after returning from the moon. I first met him 20 years ago when I introduced him before he gave a talk to a group of kids, and while any good public hero in a situation like that can convey the sense that there is no place else he’d rather be, Cernan’s enthusiasm seemed impossible to fake. Over the years, off stage, with no audience to please, he would repeat his belief that waking children up to the promise and sublime strangeness of space was indeed what he saw as his post-lunar purpose.

I last saw Cernan just last year, at the premiere of the film based on his autobiography, The Last Man on the Moon. I caught his eye in the scrum of well-wishers surrounding him and at first he gave me the practiced how-are-ya nod that celebrities always give people they don’t know. Then he recognized me, broke away and grabbed me in an enthusiastic hug. It was a moment that I’d have swooned to imagine during the Apollo era, when, as a young boy, I imprinted on space travel the way a gosling imprints on a mama goose.

It was during that gathering too that he mentioned to me, sotto voce, that he had just come out of the hospital — somethin’-somethin’-lymphoma, he said dismissively. Then he went about the happier business of the evening.

During the question-and-answer that followed the screening, he stressed again the importance he placed on carrying the space message to children, and he repeated a favorite phrase he would include in all of the talks he gave to school groups: “Always shoot for the moon,” he’d tell the kids. “Even if you miss, you wind up among the stars.”

Cernan himself, nearly half a century removed from his moonwalk, is now among the stars. But his footprints in the lunar soil remain. Even more enduringly, so does his legacy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com