Located in a red brick building on Jackson Street, the city of East Liverpool’s latest addition couldn’t be more urgently needed. The clinic, housed inside the Family Recovery Center, will soon dispense medication that can help people recover from opioid addiction, saving them a 45 minute drive to the next-nearest clinic.

This kind of resource is critical in East Liverpool, which drew nationwide attention when the police department decided to share on social media a picture of a couple overdosed and passed out in a car with a young boy in the backseat. Publishing the photo, say local law enforcement, was the city’s cry for help.

Overdoses from heroin and opiate abuse are common in this Ohio city of 11,000, as they are in other cities like it throughout the state. In 2014, Ohio earned the dubious distinction of leading the country in opioid overdose deaths; its more than 2100 deaths account for over 7% of the national total that year. The bulk of those deaths were traced to opiates or heroin, and law enforcement and emergency room doctors are frustrated with the growing problem. “When I started here in 2011, I don’t recall having any heroin or opiate overdoses at that time,” says Dr. Charles Payne, medical director of the emergency room at East Liverpool City Hospital. “There was a case here and there. Then it was once a week, then all of a sudden today I literally don’t work a shift without having at least one overdose.”

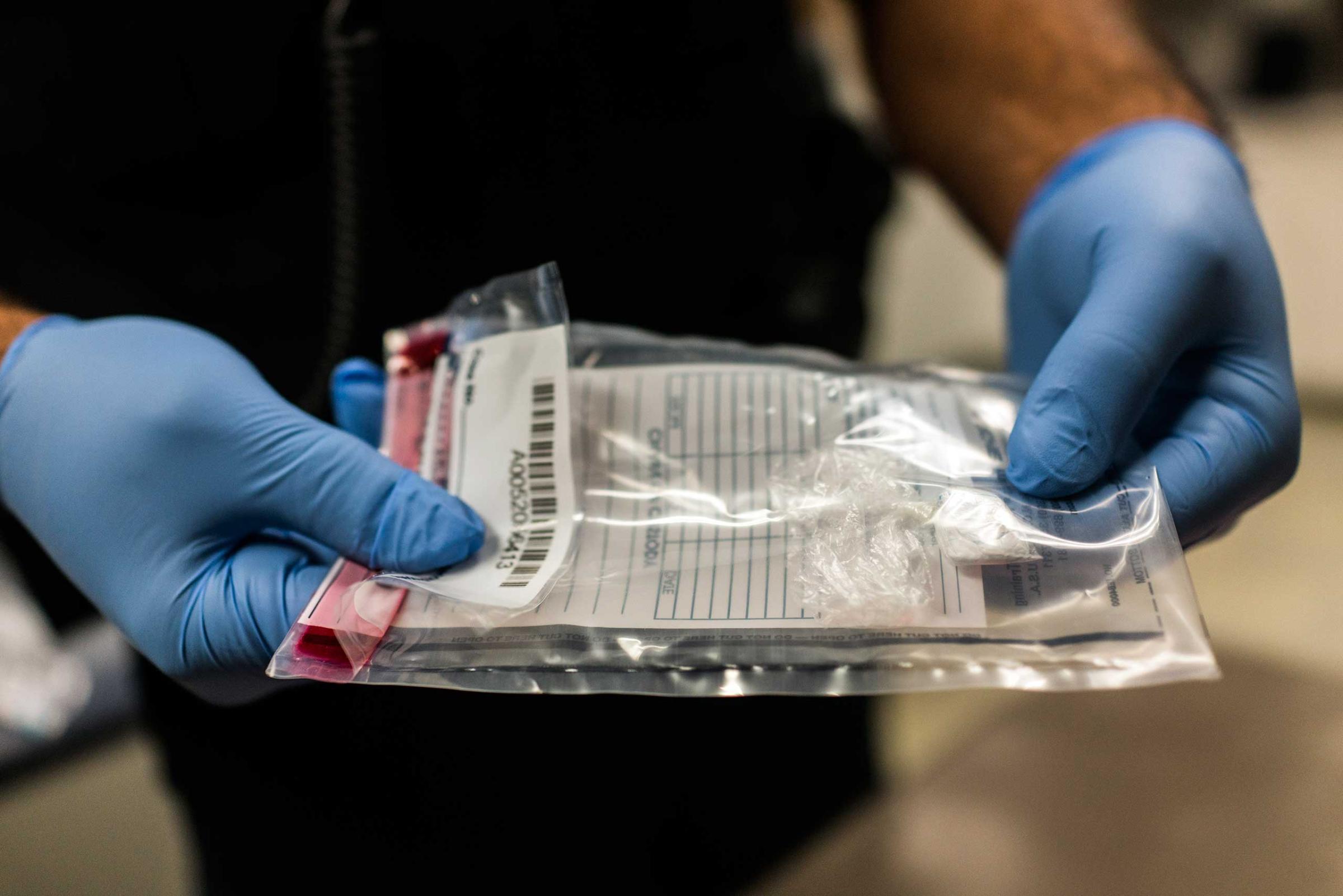

Many people who OD don’t even know what they took. Fentanyl, a synthetic analgesic that is up to 100 times more powerful than morphine, its more dangerous cousin carfentanil, which is up to 10,000 time more potent than morphine, as well as heroin and prescription painkillers like opiates are all common causes of overdose. The emergency room staff here is so accustomed to having people leave passed out addicts in their parking lot that they have a special alarm set up to alert doctors and nurses of a new case, and a dedicated gurney by the door for bringing the overdosed people in.

And it’s not just East Liverpool that is seeing this alarming rise in heroin and opioid abuse. More people died of drug overdoses in the U.S. in 2014 than in any other year, and 60% of them were because of painkillers. Over the last seven years, rates of opioid overdose deaths have quadrupled. Fueling the problem are a number of medical and cultural trends that make both legal (prescription painkillers like oxycodone and hydrocodone) and illegal opiates (such as heroin) more common. Prescriptions for opiate analgesics surged from 76 million at the beginning of the 1990s to over 200 million in 2013, as doctors attempted to better manage their patients’ pain. At the same time, man-made versions of opioids joined heroin in the illegal market, giving people more — and more dangerous — opiate drugs from which to choose.

The Controversial Way Forward

The photo of the boy has sparked debate over what created the problem in the first place, and what’s making it worse. Some public health experts argue that apart from the influx of drugs into economically struggling cities like East Liverpool, current policies for treating drug addiction have fueled the epidemic. Medications like suboxone mimic the narcotic effects of heroin and painkilling opiates without the addictive high. The medication can lower addicts’ risk of overdose death by more than 50% and their risk of relapse by more than 50% as well. After four years on the medication, a third were not abusing opioids and no longer needed suboxone to maintain their sobriety.

But its opponents, including those from national drug-rehabilitation programs, maintain that suboxone and its predecessor, methadone, are also habit-forming and therefor not appropriate for treating addiction. There are strict regulations requiring prescribing doctors to get certified to dispense the drugs, and rules limiting how many people they can treat at any one time.

The Small Town Police Force Behind the Viral Photo of an Overdose

![TIMEPOL RNC An addict living on the streets complained about the lack of rehab centers in the town and little opportunity for East Liverpool youth on Oct. 7, 2016. "I don't even know my son anymore," she said. "He's an addict [too]."](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/20161007_time_overdose_0992_14.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Still, July 2016 the Obama Administration unveiled a $1.1 billion proposal that would encourage the use of medicine like suboxone to treat people with addictions and allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants, as well as doctors, to receive the proper training to prescribe the drug.

The proposal helped bring the drug-treatment clinic to East Liverpool; it’s the only one in the county that can dispense medications to treat opiate addiction. “We’re opening the new clinic in East Liverpool due to the need in the community to give the treatment that the community and the clients need,” says Jessica O’Dea, clinical director of the Family Recovery Center.

To some, treating drug addiction with more drugs may be counterintuitive, but there is growing data to support it. Both in Switzerland and in England, health authorities actually dispense small amounts of heroin to addicts as a way to wean them off if they haven’t been successful using methadone or suboxone. “We tend to look at addiction treatment in a black-and-white way,” says Dr. Joji Suzuki, director of addiction psychiatry at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “These drug-based treatments are effective, but overall the medical culture has not embraced them.”

The key is to think of these measures more as necessary medical treatments, similar to the way people take statins to lower cholesterol or insulin to keep their blood sugar in check. People with addiction may be dependent on the drugs to keep them clean, experts say, but they are not addicted to them, since addiction, as defined in the psychiatric manual, involves severe disruption of daily activities as the craving for the next high takes precedence over all else. Study after study supports the effectiveness of drug-based therapies for opiate addiction. People who take methadone and suboxone are better able to keep a job, avoid relapses and gradually reduce their need to continue using heroin or opioids.

What’s Next

With the new clinic, O’Dea is hoping that more people are educated about the dangers of prescription painkillers, and, just as importantly, about the best ways to treat addiction. But she is concerned that more publicity of overdoses may be a double-edge sword, especially if they depict people in compromising situations. There’s a difficult balance between raising awareness about a problem like addiction and turning that attention into something counter productive. “As a clinician, I feel that it’s my job to advocate for people struggling with addiction,” she says. “I think that posting photos of addicts does probably have them feel pretty shameful and embarrassed. These pictures might keep somebody from reaching out for help.”

Still, with an epidemic as powerful as opioid addiction, it’s important for recovery experts, law enforcement and the community to coordinate their efforts to educate and support people with addiction. And O’Dea admits that the photo of the boy did make the clinic possible. “That picture started getting agencies and policy makers, and law enforcement talking about the epidemic going on,” she says. “It drew attention to more resources, and access for people needing treatment.”

Alice Park is a writer at TIME. Follow her on Twitter.

Paul Moakley, who produced this video, is TIME’s deputy director of photography and visual enterprise.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com