Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time . com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

Though such a move might seem unusual today, American parents of the past did sometimes give their children names like John Quincy Adams Miller and Woodrow Wilson Smith. What’s the history behind that White-House-worthy naming tradition, and what happened to it?

When this question first came in from a reader, the first person to spring to mind was perhaps the most famous example of a presidential namesake: George Washington Carver. Maybe his story could help illuminate the history of these types of names. But, as it happens, Carver’s parents weren’t the ones to make the presidential connection. Carver chose his own middle name, having selected a middle initial to avoid confusion with another George Carver.

As Carver’s story shows, there are plenty of reasons for choosing a particular name for an infant, from honoring a relative to merely liking a sound. In early American history, Puritans often named children after virtues like Patience or Hope, or with the surnames of family members or godparents.

This tradition—using the last name of the beloved person as the first name of the child—eventually expanded to include people who did not have a personal relationship with the parents. “After the Revolution this became a way to honour famous men,” wrote Cleveland K. Evans in the Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. “Presidents like Washington and Madison; statesmen like Franklin” and others “provided popular male names.”

In the U.S., presidents have long been seen as exemplars of national values, which made their names particularly meaningful, as they were both familiar and carried positive associations. Frank Nuessel, author of The Study of Names: A Guide to the Principles and Topics, says that sometimes a famous person will have “caught the consciousness of the public, and a lot of people name their children after a famous person hoping that by giving them this name they’ll have some of the characteristics of the person.” In a sense, says Nuessel, it’s sort of like “name magic, by using the name of a famous person, that will rub off on their child.”

The idea that a name could provide a link between a newborn and a great man continued at least until the mid-20th century. The John F. Kennedy Library has a small section of correspondence about babies named after him. Many letters speak of the honor it is for Kennedy and kindness of the parents to do so. One father wrote a handwritten letter to tell Kennedy of his newborn, “Yes we named it after you, and surely hope it brings you the very best of luck.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

While matching names aren’t necessarily a sign that a baby is specifically named after a president, a number of researchers have analyzed the popularity of presidents’ given names over time, finding the name’s popularity increases when they’re elected and dissipates over the course of their term in office.

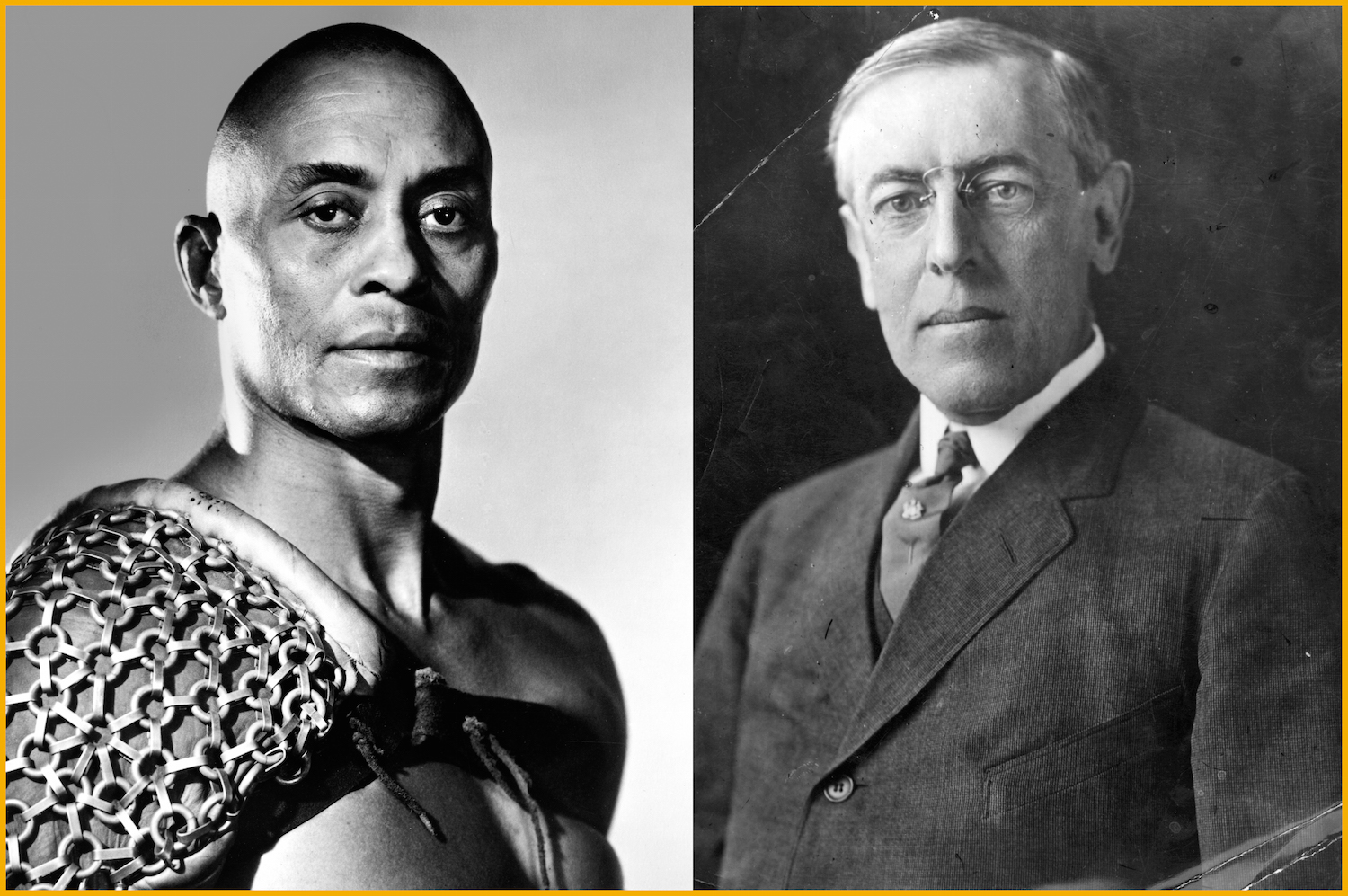

One researcher, examining data from the Social Security Administration, found that in the past century only Bill Clinton and Richard Nixon saw the popularity of their names decrease after they took office, and that there have been (relatively minor) bumps in the popularity of other recent presidential names. For example, not a few babies were named after Barack Obama, whose name was only given to five children in 2007; the following year, when he was elected, there were 52 babies with the name Barack. In his first year in office there were 69, at which point the number began to decline. That’s a pretty big increase, but not quite like Woodrow Wilson’s: there were 121 baby boys named Woodrow in 1911, and a whopping 1,843 boys and 11 girls with the name in 1912, the year he was elected. (Two years later in 1914, Woodrow Wilson Woolwine “Woody” Strode, a football player and actor, was born and joined the ranks of those named for the 28th president.)

While it’s easy to determine the influence of unusually named presidents, who might be the only public figure with that name, it’s less clear how to gauge the lingering sway of past presidential greats like George Washington or Abraham Lincoln, when their first names could just as easily honor some other George or Abraham. Even so, there is some evidence that the presidential association makes a difference.

“The magnitude can vary greatly depending on which president,” says Peter Rogerson, a professor of geography and biostatistics. “Of course it’s a little easier to pick out these things for more unique names like Calvin and Dwight and Herbert and a little more difficult when you’ve got a popular name.” To find out more about some of those common names he explored the connection between the names given to babies and their birth dates as recorded in the Social Security Death Index. The idea is that on a date of particular significance to a president, such as the president’s birthday or July Fourth, more people may think of them and their names would more likely come to mind for new parents. It turns out that the name George was 355% more popular on George Washington’s Feb. 22 birthday than would be expected given the name’s general popularity (with more than 13,000 additional newborns named George on that day, over the years, than would expected on some other day). In the centuries since his death, Washington’s name continued to inspire children named in his honor. The same was true of other past presidents’ first names, though generally the increases were less dramatic. Exceptions include Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Lincoln, both of whom had large birthday bumps. (Furthermore, another analysis in Slate found that babies were more frequently named Franklin at significant moments during FDR’s time in office, with peaks when he first won the election, the month of the inauguration and his subsequent re-elections.)

So, while we might think of presidential baby names as a thing of the past, that’s not entirely true — but there was a turning point when the tradition began to fade, and the turning point’s name was “Richard.”

Statistician Howard Steven Friedman used U.S. census data ranking the popularity of baby names to look at the relative popularity of presidents’ names. He found that almost all of the early-20th century presidents saw their names rise in the rankings after they took office—until after about 50 years ago, when Richard Nixon was president. Friedman has argued that the change wasn’t simply the result of a trend of parents preferring unusual names, since that wouldn’t specifically change the ranking popularity of the names in question. His guess? The decline in the number of babies sharing their names with a president is tied to a post-Nixon decline in the prestige associated with the office, and increasingly polarized political parties.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com