A new film, The Founder, starring Michael Keaton as McDonald’s founding chairman Ray Kroc, is about to serve up a dollop of American nostalgia. It’s a notable moment, given McDonald’s notorious resistance to outside scrutiny. The only existing written history of the company was composed under the watchful eye of its executives, way back in 1986.

The story of how Kroc morphed a simple idea sprouted in the California desert into an international empire that changed the way the world ate is studied in business schools around the world even today, though it’s most typically told through the lens of unchallenged mythology. How Ray wrested control from the brothers who masterminded assembly-line food production is certainly an interesting drama—especially since he got rich and all the credit. Meanwhile, Dick and Mac McDonald recessed into the background with the $2.7 million they requested to walk away.

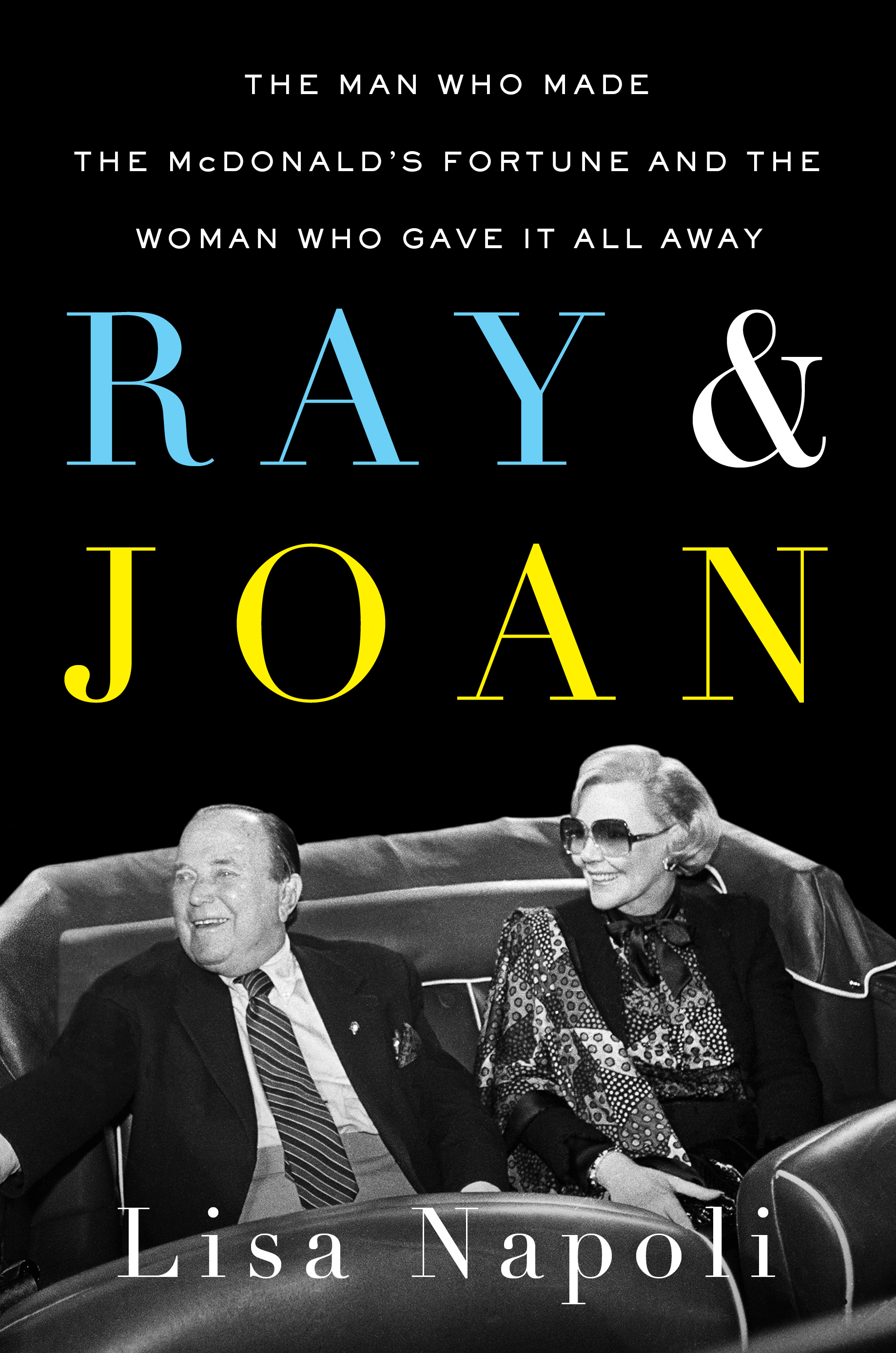

The early roots of McDonald’s certainly makes for an amusing movie, but a far juicier tale that only makes a brief appearance in the film is that of Ray’s formidable and largely unsung third wife. Joan Kroc parlayed his fortune to become one of the greatest philanthropists of the 20th century, inventively supporting liberal causes that would have made the conservative businessman recoil in horror. Some called her “St. Joan of the Golden Arches,” but what made Joan so compelling is that she was hardly angelic, but, rather, an iron-willed Tinkerbell with a streak of capricious.

Her relationship with Ray was straight out of Peyton Place. She was 28 and married to a man named Rollie Smith when she collided with Kroc, 52, in 1957 in St. Paul, Minnesota. A former paper cup and milkshake machine salesman, Kroc, also married, was by then peddling franchises around the mid-west on behalf of the McDonald brothers. Their hamburger stand in San Bernardino, one of countless such operations on the emerging byways of post-War America, had emerged as a runaway success because of their spare menu and well-choreographed “Speedee” system of service they’d artfully charted out on a tennis court.

The beautiful, blonde Joan serenaded diners at an upscale restaurant on a Hammond organ, one of three jobs she held to help her family make ends meet. Ray, himself a pianist, was smitten by her musical proficiency, not to mention her striking good looks. Soon, Joan’s employer, Jim Zien, was buying in to the fast-food game and, not coincidentally, hiring Joan’s husband to manage his McDonald’s outpost in St. Louis Park—store number 93.

With a bonus Rollie earned for his hard work, he, Joan and their daughter decamped to Rapid City in 1959 for the chance to open the first outpost of the fast-food chain in South Dakota. Relocation for the earliest franchisees was not uncommon—the better to fan out McDonald’s across the land. Wives were the only women allowed then to work at the hamburger stands. (Unpaid, of course—and out of sight.) From the back office, she dutifully placed orders to local suppliers for potatoes and such, helping to launch her husband as a successful franchisee with store number 223. Food was locally sourced back then, and a carefully constructed guidebook offered paint-by-numbers instructions.

Twelve years and numerous dramatic detours later—including a divorce and second marriage for Ray—Joan finally accepted his proposal.

Money did little to help Joan cope with her new husband’s “violent, ungovernable temper,” as it was described in divorce papers she filed in 1971, addled by his affinity for Early Times whiskey. Joan decided to stay in the marriage and, with only a high school education, dedicated herself to launching an innovative alcoholism addiction charity called Operation Cork (Kroc spelled backwards, she explained.) She produced made-for-TV dramas about the impact of drinking on the family, like Soft is the Heart of a Child, and when Dear Abby mentioned a free booklet Joan commissioned called Alcoholism: A Family Affair, her offices were deluged with requests from around the world. She convened conferences of social workers and doctors performing groundbreaking work to address the problem—including getting the medical school curriculum updated to include more than the passing glance it gave toward addiction. All this before First Lady Betty Ford came forth with her own struggles; Joan later funded her efforts.

After his death in 1984, she inherited his controlling stake in the company, and almost immediately began giving it away. In the aftermath of a mass murder at a McDonald’s in San Diego, she launched a victim’s fund with a generous personal donation, even before the corporation had responded. For the rest of her life, she practiced such radical, ecstatic giving, sometimes calculated, other times in response to a news story that irked her, or a person she met on a plane. She was an early proponent and funder of hospice and AIDS research; a funder of Norman Cousins’ pioneering work at UCLA in the study of the mind’s effect on health and disease resistance; the first individual to give a million dollar gift to the Democrats; and a passionate, active supporter of the no-nukes movement.

This is not to suggest she lived the life of a do-gooding ascetic. She deployed her Gulfstream jet like a taxi, ferrying friends to Vegas for gambling marathon sessions, smoking like a fiend all the way. An animal-lover, she thought nothing of sending her plane to fetch a breeder of her favorite Cavalier King Charles spaniel to deliver her a new pet. Other times, the jet transported the body of her dear, departed friend Father Henri Nouwen to his final resting place.

Diagnosed with terminal brain cancer in 2003, she craftily held a Clue-like birthday party for herself to which she invited guests who had no idea of her illness—or that they were about to become beneficiaries of her vast estate. Her posthumous $235 million gift to NPR is credited with putting the network on sound financial footing, and her $2 billion gift to the Salvation Army created several dozen world-class recreation facilities in poor neighborhoods around the country. She never forgot the roots of her fortune, though. Around the fancy neighborhood of Rancho Santa Fe, where she made her last home, she was known to drive through the McDonald’s to pick up a snack, sometimes forgetting her purse, other times offering $100 tips. She’d count the days each year till Halloween, when she’d dress up and dispense treats to neighborhood kids.

The story of McDonald’s is, like it or not, an indelible part of American history. But more compelling than the founder is the woman who, a stylishly dressed Robin Hood with a meticulously hairdo, took his fortune and practiced wide-ranging compassion. When you learn about Joan, you’ll never look at a Big Mac the same way again.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com