1. Pinocchio

For his follow-up to Snow White, Walt Disney developed a plotline that would anchor many animated features (Kung Fu Panda, Tangled, Happy Feet, The Little Mermaid, just to name four on this list): the coming-of-age film. Based on an 1883 story by Carlo Collodi and under the superb supervision of Hamilton Luske and Ben Sharpsteen, Pinocchio taught the lesson that a child is not human until he can feel loss and act with spontaneous generosity.

Whereas Snow White stuck to recognizably human forms — the script could almost have been shot as a live-action film — Pinocchio liberated the Disney animators. The movie boasts all manner of creatures: human (the woodcarver Gepetto), ethereal (the Blue Fairy), vulpine (J. Worthington Foxfellow), feline (Gideon) and bizarre hybrids. With freedom came challenges: finding a visual coherence for a landscape that included creatures as small as Jiminy Cricket and as large as Monstro the Whale (who was about the size of a three-story building).

A significant advance in narrative power and multiplane-camera technique over Snow White, the movie also taught moral lessons in the most useful way: by scaring the poop out of the little ones. If you tell a lie, your nose will grow; Pinocchio’s proboscis swells to Cyrano dimensions. If you run away from home, you could die; as the seductive kidnapper Stromboli tells the wooden boy, “When you grow too old, you will make good firewood.” Lured to Pleasure Island on the promise of making mischief away from adults’ censorious eyes, Pinocchio and his pals indulge in shooting pool, chugging alcohol and puffing on cigars. (Greatest antismoking PSA ever.) In fact, Pleasure Island is a concentration camp where bad boys are transformed into donkeys. In one of the scariest scenes in film history, Pinocchio’s pal Lampwick laughs at his friend, and a donkey’s hee-haw comes out. (Bizarrely, in the 1980s, Disney named a nighttime theme park in Florida after this awful prison.) Far from coddling his youngest customers, Walt Disney here portrayed childhood as an unrelenting series of nightmares.

The boldest of Disney’s horror homilies is also the most powerful demonstration of the ability of a medium supposedly aimed at kids to evoke persuasive motion and deep human emotion. The story of a puppet who wants to be a real live boy also serves as an allegory for the work of the Disney geniuses — and all the great animators whose works are included here — who start with pencil and ink, or pixels, or silhouettes, or plasticine figurines, and create vivid characters that live forever inside the small, enthralled child that is every moviegoer.

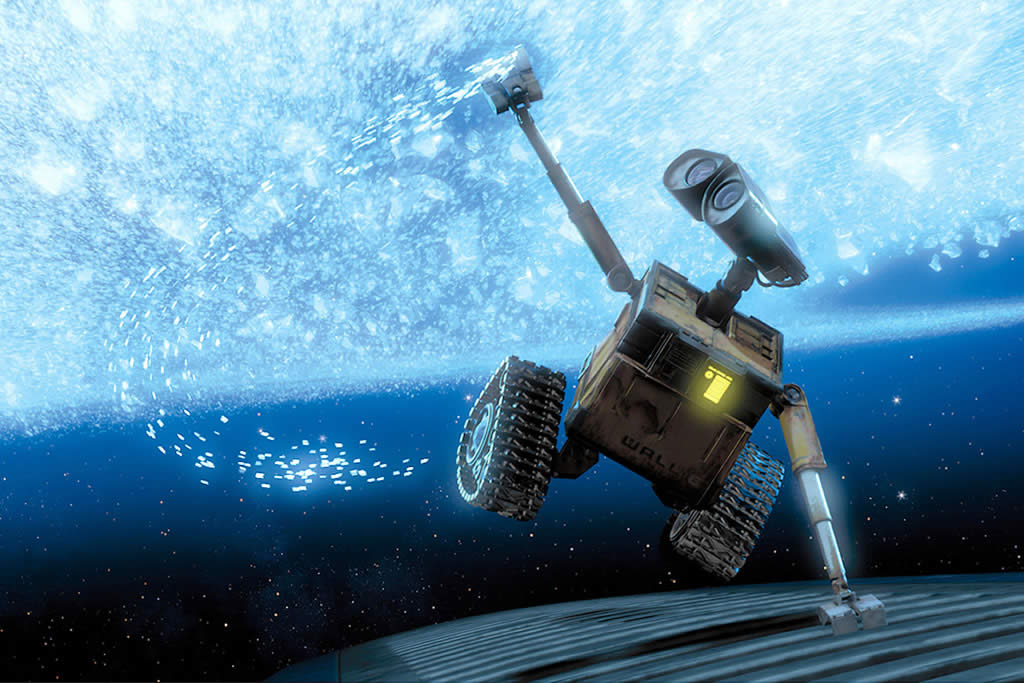

2. WALL•E

Hundreds of years into the future, planet Earth has become a dump heap so huge that humans have fled into the stratosphere to be coddled by machines on a giant spaceship. The only signs of life back home are that unkillable bugger, the cockroach, and a trash cube with binocular eyes, forklift plates for arms and Caterpillar tracks to navigate the rough terrain. The thing is called a Waste Allocation Load Lifter, Earth-Class — WALL•E — and its job is to clean up the mess of consumerism run amok. It can speak only in electronic grunts and sighs; when it is visited by a more advanced robot named EVE (for Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator), they communicate in one-word bursts.

The first half-hour of Andrew Stanton’s enthralling environmental parable is virtually wordless but has an almost symphonic aural richness, thanks to Ben Burtt’s intricate sound design. (He was also the voice of WALL•E.) In a movie that shows but doesn’t tell and whose leading characters are essentially mimes, Stanton clarifies for even the youngest viewer that machines have heart and soul. Less a trash collector than a trash connoisseur, WALL•E is programmed to be dedicated to his job. Yet he’s a lonely guy; he putters around the late, great planet Earth like a solitary child on an abandoned playground, or an oldster among his souvenirs. WALL•E’s special ache is his nostalgia for a life he never lived, for the intimate connection only humans enjoy. And when he finds EVE, he shows that machines can be, in the phrase from Blade Runner, more human than human.

All the major Pixar features, from Toy Story right through to Toy Story 3, have the means of astonishment. The company doesn’t make cute movies for kids; it tells universal stories through a graphic language so persuasive that children and adults respond with the same pleasure and awe. And WALL•E is the perfect culmination of John Lasseter’s first two-minute short, Luxo Jr., brought to its logical and thrilling romantic extension: toy meets girl.

3. The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie

All right, this is cheating: including in this countdown a collection of shorts that (unlike Fantasia) were not made as part of an animated feature. Yet this feature-length medley of Chuck Jones cartoons from his postwar peak period at Warner Bros. has too much wit, melodrama and sheer delight not to be placed high on any list of animation achievements. Taken together, the 10 shorts compiled here — Hare-Way to the Stars, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, Robin Hood Daffy, Duck Amuck, Bully for Bugs, Ali Baba Bunny, Rabbit Fire, For Scent-imental Reasons, Long-Haired Hare, What’s Opera, Doc? and Operation Rabbit — could serve as a child’s finest introduction to the raucous rapture of the animated film.

Warner Bros. shorts always shamed Disney’s in the creation of memorable anthropomorphs. Jones and writer Michael Maltese turned Porky Pig, once just a cute piglet, into a harassed middle-management type. Elmer Fudd was the chronic, choleric dupe, Sylvester J. Pussycat a feline of sputtering theatrical bombast. Bugs became the cartoon Cagney — urban, crafty, pugnacious — and then the unflappable underhare who wins every battle without ever mussing his aplomb. And Daffy … ah, Daffy! Here was modern man (well, modern mallard) in all his epic scheming and human frustration. He would debate with Bugs on the time of year (“Rabbit season!” “Duck season!”) before a shooting accident would require reconstructive surgery, as his quacking bill was suddenly on the back on his head. Pleading or wheedling or just staring ahead with a mutely eloquent resignation, Daffy embraced multitudes — multitudes of losers, us on our worst day. Multitudes of Chuck too: Jones later said that Bugs was the person he wished he could be and that Daffy was the person he probably was.

A staple of 35 years of Saturday matinees, the Jones cartoons — and those of his cartoon compadres Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, Friz Freleng and Robert McKimson — rarely got official notice, even in the Academy Award category for Animated Short. (Only “For Scent-imental Reasons” copped an Oscar for Jones.) Yet these films were more than amusing, more than an excuse to escape reality. They were reality, transformed into art: brutally true, honorably honest, like Samuel Beckett with the fun up front. Jones was a genius of comic movement and dialogue and a genuine animator — he breathed soul into his creatures. Maybe children were his raptest audience, but his films were not merely kids’ stuff. As Jones often said, “We weren’t making them for kids, or for adults. We were making them for ourselves.” And, a grateful viewer has to say, for the best part of our selves.

What’s art, Doc? This is.

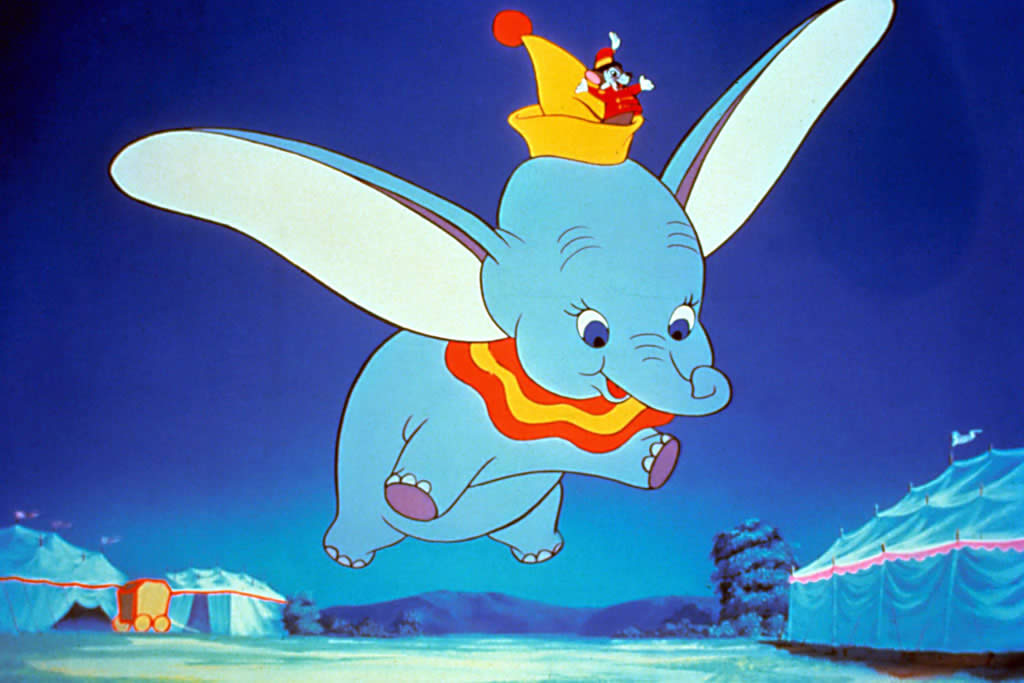

4. Dumbo

In his first years as a producer of animated features, Walt Disney was the most ambitious man in Hollywood; Orson Welles’ dreams were pallid by comparison. Disney topped the breakthrough Snow White with the pinnacle of Pinocchio, then set about wedding classical music to sophisticated, sometimes abstract cartooning in the two-hour Fantasia. (“Gee,” Walt said about the movie’s “Rite of Spring” segment, “this’ll make Stravinsky!”) But between Fantasia and the 1942 Bambi — the last fully animated single-narrative feature the studio would make until the 1950 Cinderella — the team tossed out one “little” film that nobody was planning as a classic. Just 64 min. long and made quickly for under $1 million, Dumbo was filler. Also prime and primal Disney.

In director Ben Sharpsteen’s telling of a story by Helen Aberson and Harold Pearl, a circus elephant named Jumbo Jr., is cruelly renamed Dumbo because of his big ears. Adhering to the by-now-standard Disney torture test for young viewers, Dumbo’s frantic mother is taken away to a “mad house” after causing a stampede. Alone in the world, the child pachyderm must take his friends where he finds them: in a sprightly mouse named Timothy and some wisecracking crows. In the tradition of children’s literature, Dumbo’s deformity proves an asset: he can fly!

Today’s moviegoers may take offense at the black stereotyping of the crow quartet, though their saucy humor is indistinguishable (in a G-rated way) from the antic characters in Barbershop or Friday. Dumbo, who never speaks, is a poignant silent clown in the tradition of Buster Keaton (the “Great Stone Face”) or Harry Langdon (the big baby), except that this big baby — and the simple, lovely fable he stars in — kept moviegoers from infant to senior smiling and sobbing for 70 years straight.

5. Spirited Away

On a detour during a family drive, 10-year-old Chihiro and her parents discover what Dad calls “an abandoned theme park.” It’s really a sort of ghost spa — a Bathhouse on Haunted Hill — where she is a prisoner and her parents have been turned into swine. (They were bewitched because “they ate like pigs”; at this theme park, you are how you eat.) The frightened Chihiro realizes she must tap unused reserves of courage and ingenuity to escape.

Hayao Miyazaki is the world’s most revered master of animation (My Neighbor Totoro, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, Ponyo), and this is his masterpiece. In Chihiro he has created a bold child who, like Lewis Carroll’s Alice or L. Frank Baum’s Dorothy, is both amazed and troubled by the kingdom in which she is a captive. The bathhouse, which welcomes tired ghosts from the far reaches of the spirit world, is run by Yubaba, a wicked queen with a huge head; her enforcers are three severed heads that follow her like bowling balls with a grudge. Hundreds of critters, each with a distinct personality, populate the descending circles of this teeming dictatorship. In the boiler room, Kamagi, a six-armed troll, keeps stern watch over dozens of soot-ball slaves — cute vermin, thrilled when Chihiro shows up to lighten their workload. The child’s best hope for fleeing Yubaba on the undersea railroad is young Haku, a boy who can assume the shape of a dragon. When Chihiro and this beautiful beast take to the sky, they express the most elevated forms of teamwork and puppy love.

The animation doesn’t boast the meticulously rendered character expressions of the early Disney features. Nor does it aim for the slam-bang effects of DreamWorks’ computerized cartoons. Instead, Miyazaki goes for, and gets, the big picture, the grand emotion, one spectacular set piece stacked on another in brilliant colors and design. There’s not a more impressive sequence in recent movies than the arrival at the bathhouse of a huge, amorphous river god, encased in centuries’ worth of stink and sludge, whom Chihiro has the daunting task of giving a sturdy wash and scrub. Spirited Away is handcrafted art, as personal as an Utamaro painting, yet its breadth and depth gave it a worldwide appeal.

6. South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut

Some people would be advised to skip the feature-length cartoon based on the Comedy Central series. A short list would include celebrities teased in the movie: the Baldwin brothers, Conan O’Brien, Winona Ryder, Bill Gates, Liza Minnelli, Barbra Streisand and God. Also anyone who lacks a bottomless tolerance for inspired comic rudeness. To the rest of you: enjoy the flat-out funniest movie on this list — though with an R rating, it’s obviously not for children.

The kids from Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s TV series, by 2011 in its 15th year, are all here. But this time Stan, Kyle, Kenny and Cartman — the quartet of cut-out third graders in the “quiet little redneck podunk white-trash mountain town” of South Park, Colo. — are out to save the world, along with their favorite Canadian gross-out comics, Terrance and Phillip. While three of the boys join a kids’ resistance, Kenny (the dead one) goes to hell, where Satan is playing footsie — and other body parts — with Saddam Hussein.

Parker’s not-so-secret sin is that — virtually alone among heterosexuals under 50 — he loves the grand ambitions and soaring chords of old Broadway songs. Abetted by super-arranger Marc Shaiman (who later did the shows Hairspray and Catch Me If You Can), he turned the South Park movie into a wall-to-wall musical: 14 tunes, each evoking a familiar Broadway style. Cartman’s perky “Kyle’s Mom’s a Bitch” echoes Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, with choruses in fake Chinese, Dutch and French. Saddam could be an Arabic fiddler on the roof as he struts his seedy charm in “I Can Change.” Satan has a hilariously solemn ballad in the Disney-cartoon mode; like the Little Mermaid, he wants to be “Up There.” And though a song whose refrain is, more or less, “Shut your flicking face, Uncle Flicka” would seem to have little room for musical wit, Shaiman turns it into an Oklahoma hoedown, with kids chirping like obscene Chipmunks. Come for the dirty jokes; stay for the finest, sassiest full-movie musical score since the disbanding of the Freed unit at MGM.

7. Up

One sequence, toward the beginning of Pete Docter’s old-man-and-a-kid romance, made everyone fall for Up. In the 1930s, Carl, a preteen adventurer (if only in his mind), hopes one day to visit Paradise Falls in remote South America; then he meets a girl named Ellie, whose daring matches his dreams, and it’s love at first sight. A tender montage synopsizes a half-century of their life together: the wedding, the fixing up of their home, the quiet walks, their respective jobs at the local zoo (her tending the animals, he selling balloons), their eager preparations for a child they later learn they can’t have, their need to defer the big trip to Paradise Falls to pay for home improvements, then her slowing pace and death. This series of vignettes is played without dialogue and underscored by Michael Giacchino’s wistful waltz. It’s the sweetest, saddest 4½ min. you’ll ever see in a movie.

With the love of his life gone, widower Carl (voiced by Ed Asner) might as well be dead. His home is really a mausoleum, and he is both caretaker and corpse. We never heard the mature Carl say a word to Ellie while she was alive, but now he talks nonstop to his absent darling. She’d understand his bitterness; she might even forgive it. And she’d surely approve of his decision to fly to Paradise Falls — in his own house, to which he has attached 20,000 helium-filled balloons. What he doesn’t expect is that he will have company: a Wilderness Ranger named Russell, who’s about the same age Carl was when he met Ellie.

Up revels in a minimum of dialogue, deft comic underplaying and a style the Pixar people call “simplexity” — a character design that stresses circles and cubes. Carl looks like a trash-compacted Spencer Tracy in his later years; Ellie is curvy; and the round Russell might be another balloon. The visual scheme also goes for contrasts: Carl’s home has a muted, almost funereal palette, while the South American flora and fauna form a ravishing fiesta of color. From the fairly radical notion of a family feature about a mean old man who literally and figuratively learns to let go, Docter and co-director and co-writer Bob Peterson sent Carl and the audience on a journey in two new directions: penetratingly inward and exaltedly up.

8. The Triplets of Belleville

The string of Pixar hits and the mammoth worldwide gross for DreamWorks’ Shrek gave movie studios the signal to dump hand-drawn 2-D animation for the shinier, more popular CGI. Apparently Sylvain Chomet didn’t get the news. The French comic-strip artist spent five years making The Triplets of Belleville (also known as Belleville Rendez-vous), about an old woman who raises her grandson to be a Tour de France champion. There’s a dog, some bike-napping mafiosi and three old chanteuses whose diet consists entirely of frogs they catch by tossing hand grenades into a nearby stream. Vous guessed it by now: Triplets is terrific.

Chomet, who seven years later made the Jacques Tati–inspired The Illusionist — and who, for Triplets, did use computer animation for the film’s cars, boats and trains — has a canny design eye to match his narrative wit. The old woman is stocky and clubfooted, a compact metaphor for stubborn dedication; her grandson is so spindly, he could ride Giacometti’s chariot; Bruno the dog has more personality than 101 dalmatians. The movie isn’t aimed at kids, but they will find plenty to beguile them. And don’t worry that the film is French; it has hardly any dialogue. Doesn’t need it. There’s eloquence enough in the movie’s gnarly imagery and Chomet’s understanding of the human impulse not just to survive but also to save others.

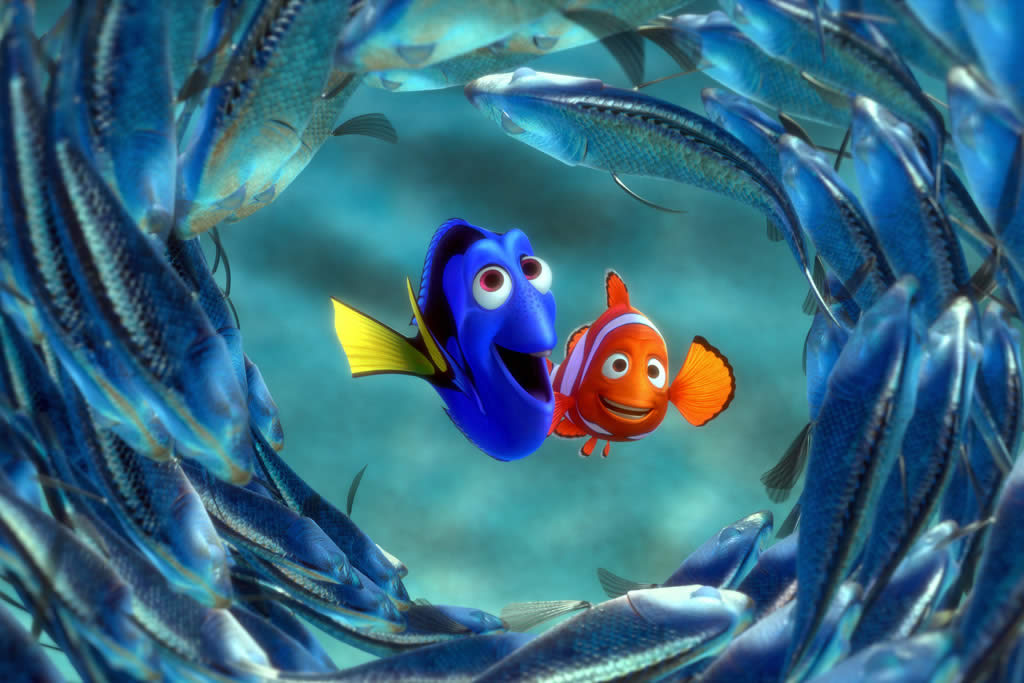

9. Finding Nemo

Marlin the clown fish (voiced by Albert Brooks) is a fussy little anxiety machine. When he learns he’s to be a father of 400 babies, he fidgets: “What if they don’t like me?” But he’s right to be concerned for his brood in the fish-eat-fish world of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. A shark devours Marlin’s wife and 399 of her eggs. That leaves little Nemo (Alexander Gould) — the one survivor, handicapped by an underdeveloped fin — and Marlin, burdened with an overdeveloped sense of dread. When Nemo is old enough to go to school (of fish), Dad’s pessimism is again validated: the lad defiantly swims into open water and is kidnapped. Marlin must conquer his own fear of the great wet world, that “swirling vortex of terror.” But he has a companion in his search: Dory (Ellen DeGeneres), a blue tang with a sunny disposition and a short-term-memory problem.

The Pixar pixies always fashion funny, poignant stories to match their gorgeous computer images, and this time they hit the jackpot, in a lost-child saga told from the searching father’s point of view. With its ravishing underwater fantasia, Nemo trumps the design glamour of earlier Pixar films. The dramatic set pieces — Marlin and Dory eluding jellyfish stings, Nemo’s claustrophobic panic in a plastic bag — are realized with assured energy and balanced by the voice artists’ deft comic performances. Writer-director Andrew Stanton provides artistic and political resonances galore: he alludes to favorite movies, from Pinocchio to Psycho, and fearlessly takes on the powerful pet-shop and aquarium lobbies. There is also the secret insignia of any Pixar feature: a G-rated fart joke. Nemo was the highest-grossing CGI feature of its time and is one of two animated features on the All-TIME 100 movie list. It was, and remains, a serene marine enchantment.

10. The Little Mermaid

When Disney animation boss Jeffrey Katzenberg teamed writer-directors Ron Clements and John Musker (who later did Aladdin, Hercules and The Princess and the Frog) with songwriters Alan Menken and Howard Ashman (Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin), he birthed the studio’s first renaissance feature. Here was everything that mostly had been missing in the two decades since Walt’s death: an assured lightness in the narrative, a blending of classic and contemporary design and a sheaf of catchy songs that could command the top of the pops while lodging in older fans’ internal jukeboxes. For the next five years, until Katzenberg left the company and formed DreamWorks, Disney animated features were among the smartest films around and proved that the Hollywood cartoon had become the last, best refuge of the Broadway musical.

From the first moments, when the mermaid Ariel (voiced and sung by Jodi Benson) dreams of being part of the world above, to an ending that comes with flourishes, a rainbow and a perfect kiss with full heartstring accompaniment, this fish-out-of-water fable is a model of buoyancy and poignancy. Updating the Hans Christian Andersen tale about the prince and the sea creature — basically, boy meets gill — Musker and Clements inserted a modest political message (similar to those of Finding Nemo and Happy Feet) that pegs humans as, in the words of Ariel’s father, “spineless, savage, harpooning fish eaters.” But those are so many bubbles in this effervescent delight. The film’s vocal, musical and painterly talents mesh ecstatically in the big water-ballet production number “Under the Sea.” As Sebastian the crab (Samuel E. Wright) limns the aquatic virtues, a Noah’s aquarium of sea creatures animates a joyous Busby Berkeley palette. And that’s just one of many highlights in 82 min. of canny magic.

11. Toy Story 3

Of Pixar’s first 11 features, nine were gleaming originals. The two sequels: Toy Story 2, in 1999, and this splendid apex of the trilogy, directed by Lee Unkrich and scripted by Michael Arndt. The boy Andy is now ready for college, and his toys, which he hasn’t played with for years, are mistakenly thrown out. They find refuge in Sunnyside Day Care, which has kids galore — no toy left behind — and new friends, including Lotso (Ned Beatty), a folksy stuffed bear with a strawberry scent. If only the 2-year-olds to whom Buzz and the rest are assigned as playthings weren’t such violent little beasts. If only Lotso didn’t have a hidden agenda. If only the toys from the first two films didn’t have to attempt a great escape that leads to a horrifying holocaust. Unkrich called it “taking toys to their endgame.”

The scariest, life-threateningest Pixar movie is also a powerful fable about needy wage slaves being wedded to their servitude because it creates a sense of community more liberating than freedom. Toy Story 3 teaches morals of holding and sharing, and personal responsibility to the greater social good. But the movie’s most important lesson is for Hollywood: Watch this and see how it’s done.

12. Toy Story

The revolution began here. In the mid-1980s, John Lasseter, a Disney alumnus, joined the Marin County, California, computer lab Pixar and, to demonstrate the narrative and plastic potential of computer-generated animation, made three terrific shorts (Luxo Jr., Red’s Dream and Tin Toy) that invested metal objects such as lamps, unicycles and drummer-boy toys with life and heart. They showed that things have wills and wits of their own and exist in intimate relation to their human masters — and are funnier too. Whence sprang Toy Story, the first full-length film created wholly on computers and one of the most inventive comedies of its decade. For when a genius like Lasseter sits at his computer, the machine becomes more than just a supple paintbrush. Like the creatures he dreamed up, it’s alive!

In Andy’s bedroom, the toys are alive. They and their leader, the cloth cowboy Woody (voiced by Tom Hanks), are working stiffs with the fear, every time a birthday approaches, that they will be replaced by more sophisticated gewgaws. One arrives in the form of an action figure called Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen). Buzz’s power is that he seduces the old toys, and presumably Andy, with his space-age gadgetry. His problem is that he thinks he’s human. So here, recognizably and delightfully, are two weird dudes: a political boss stripped of his moral authority and taking it with a lack of good grace, and a hero who is deeply delusional.

Like a Bosch painting or a Mad comic book, Toy Story created a world bustling with strange creatures and furtive, furry humor. What even Lasseter couldn’t predict was that audiences would instantly fall in love with the shiny surfaces and supple movements of the CGI technique — or that within a few years, it would consign the hand-drawn format, which had prevailed for nearly a century, to history’s dump truck. The traditional Disney style was suddenly like old-cloth Woody, and Pixar became the Buzz Lightyear of 21st-century animation.

13. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

The classic Disney style is sometimes dismissed as cutesy-poo. That wasn’t the reaction when Walt Disney released this, his first feature, following a decade of cartoon shorts that pioneered the imaginative use and sound and color. As they watched Snow White succumb to the poison apple proffered by the witch who was also her stepmother, children literally wet the seats of movie palaces, such was the primal anguish that stabbed their young years. Disney features were often the first films kids saw — and the first that forced them to confront the loss of home, parent, life. (Bambi’s mother is what?) These were horror movies with songs, Greek tragedies with a hummable chorus. They offered shock therapy to 4-year-olds, and that psychic jolt could last a lifetime.

Making an animated feature might have been the next logical step after the studio’s Oscar-winning shorts Flowers and Trees, The Three Little Pigs and The Tortoise and the Hare. But in 1934, when the project took real shape, Snow White was called “Walt’s folly”: a gamble of $1.5 million, one of the highest production budgets of the ’30s. The movie took three years to make, with David Hand as supervising director and Perce Pearce, Larry Morey, William Cottrell, Wilfred Jackson and Ben Sharpsteen in charge of individual sequences. When Walt’s wife Lillian Disney saw it, she told him, “No one’s ever gonna pay a dime to see a dwarf picture.” She underestimated the universal yearning for a fairy tale that was both grim and grand, not to mention the appeal of the Frank Churchill–Leigh Harline songs (“Some Day My Prince Will Come,” “Heigh-Ho,” “Whistle While You Work”) that would crawl into 100 million memories and stay there as the best of friends.

The movie was a smash: the top-grossing film of 1938 and, in real dollars, the 10th biggest money earner of all time. Much of that loot was earned in reissues, every seven years for the next half-century, with zillions more in home-video revenue. Parents don’t buy Snow White as a relic of antique animation; they want their kids to experience the wonder and terror they once felt — the elemental emotions that all movies should aspire to evoke.

14. The Adventures of Prince Achmed

The earliest surviving animated feature is also an example of prodigious artistry in a minimal form. Based on tales of the Arabian Nights, Lotte Reiniger’s film uses silhouette figures photographed in stop-motion against voluptuous backgrounds. A gifted designer as well as a spellbinding storyteller, Reiniger creates a cohesive visual universe through which Prince Achmed rides on his magical horse, wooing a fair princess and battling a host of demons. This silent film (Wolfgang Zeller composed the original accompanying score) may seem like an art film, but it has a zest to entrance any children or adults with open eyes and minds.

Inspired from childhood by the Chinese tradition of silhouette puppetry, Reiniger entered the teeming German film industry and devised silhouette sequences for Paul Wegener’s The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1918) and Fritz Lang’s 1922 Wagner film Siegfried’s Death. The following year, she was commissioned to make Prince Achmed, which she completed when she was just 26. Her next feature, the 1928 Dr. Dolittle and His Animals, had a score by Paul Hindemith, Kurt Weill and Paul Dessau. With Carl Koch (her husband, producer and cinematographer for 40 years), she made several animated shorts in the early years of the Third Reich before leaving for England in 1937. That was the year of Snow White, which immediately established the fuller, softer, more realistic form of animation as the norm. Reiniger died in Dettenhausen, Germany, in 1981 at the age of 82, but the glory of Prince Achmed is immortal.

15. Wallace & Gromit in the Curse of the Were-Rabbit

Wallace (voiced by Peter Sallis) is a cheerfully vague bachelor whose obsession for dreaming up elaborate contraptions almost equals his fondness for cheese. (His bookshelf contains such volumes as East of Edam, Brie Encounter and Fromage to Eternity.) Gromit, his master’s fretful servant and savior, mutely conveys his always justified anxiety via minuscule twitches of the most eloquent movie eyebrows since Groucho’s. In three short films — A Grand Day Out, the all-time fabulous The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave — Aardman Films’ Nick Park created sublime comedy through the insanely intricate form of animation known as stop-motion, in which plasticine creatures and tiny props must be posed for a single frame, then moved infinitesimally for the next. The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, the series’ expansion to feature length that Park co-directed with Steve Box, contains 122,400 shots (based on 24,000 storyboards), which explains why this mini-masterpiece took five years to make.

To protect the vegetable crops in his village and win the approval of dear Lady Tottington (Helena Bonham Carter), Wallace has invented the Bun-Vac 6000, which scoops up rabbits, painlessly, by the hundreds. (“It blows and sucks.”) But his machine is no match for the mysterious, vegemaniacal Were-Rabbit ravaging the town. The movie has some vigorous action scenes: Gromit’s World War I–style aerial combat with another canine (a real dogfight) and Lady Tottington’s housetop confrontation with the dread Were-Rabbit. The priceless exchanges, though, are between man and dog — both in the empyrean of comic artists, as are their creators.

15. Happy Feet

The last non-Pixar film to win the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, Happy Feet seduced audiences with its perky title and the story of Mumble the penguin, born to a tribe of great singers but whose only gift was for dancing (choreography provided by tap master Savion Glover). That sounds like your basic ugly-duckling fable, meant to cheer special-ed kids and their parents — a story similar to Babe, the heroic-pig saga produced by Happy Feet director George Miller. But Miller, the Australian physician and lecturer whose Mad Max trilogy imagined a postnuclear wasteland populated by feral biker gangs, and whose Babe: Pig in the City dropped its porcine star into urban depths, had darker dreams to relate.

As Mumble is separated from his tribe and wanders Antarctica with his own ragtag gang, he is buffeted by blizzards and threatened by rampaging “aliens” (the enemy is us) whose crimes against the climate are shrinking his world. (Happy Feet is film noir emotionally, film blanc visually.) Another penguin, Lovelace, is strangled by the six-pack ring carrier he wears as a “sacred talisman.” These political points made the film a favorite scourge of right-wing commentators. But moviegoers didn’t care. They took to an animated version of the basic Miller theme — the outsider who enters a community and becomes, in the director’s phrase, “an angel of change” — and danced out of any theater playing Happy Feet. A sequel is due in November.

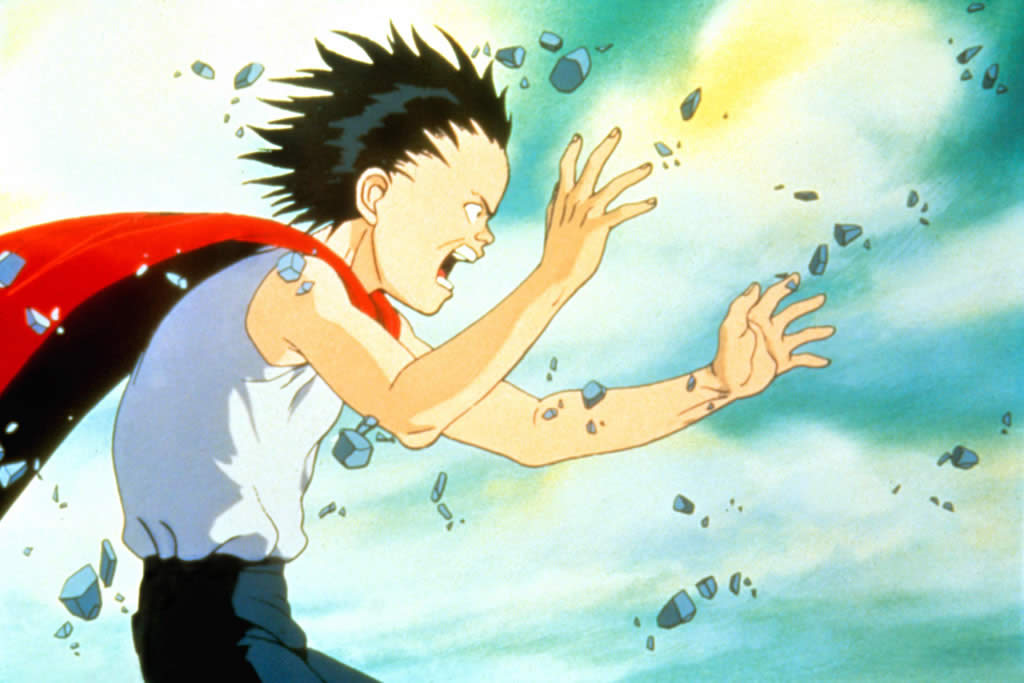

17. Akira

In 1951, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon declared to the world that Japan’s was a complex and vital national cinema. In 1988, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira introduced to many Westerners the head-swiveling richness of anime. At the time it was the country’s most expensive animated film — and the year’s biggest hit. Adventurous Americans discovered the movie in the cult section of something called video stores, a curious artifact of the late 20th century. Akira finally got a big-screen U.S. release in 2001.

Boiling his 2,182-page manga multinovel into a 2-hr. epic, Otomo retained the books’ sprawling, darn near confounding narrative while bringing a kinetic kick to its sex and violence (and violent sex). Set in Tokyo in 2019 (the same year in which Blade Runner, one of many of Otomo’s influences, was set), the film traces the convergence of teen rebel Tetsuo and his gang with a government project known only as Akira. You watch it less for the nuances of facial detail, which aren’t much more sophisticated than those in Astroboy, than for its dark glamour and noir-ish camera angles. Call it Mad Max Space Odyssey, or a cyberpunk Godzilla, or a Peckinpah bloodying-up of The Matrix (Neo-Tokyo was the postapocalyptic name of Japan’s largest city), but Akira is its own grand and startling vision.

18. The Lion King

Disney animated features had two great periods: the “classic” films in the decade that began with the 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and the “renaissance” movies in the decade that began with 1989’s The Little Mermaid. Supervised by Jeffrey Katzenberg before he left to form DreamWorks, these latter films revived Walt’s formula of comedy, heart and hummable songs. The blockbuster of the renaissance phase was this majestic epic, which added the element of high melodrama. Not since Bambi had so much been at stake in a Disney tale. There are kingdoms to be sundered, deaths to be atoned for. The father of a prince is killed, his conniving uncle seizes the throne, and the father’s ghost instructs him to seek honorable revenge. Put it another way: a boy leaves home, escapes responsibility with some genially irresponsible friends, then returns to face society’s obligations. On the grasslands of Africa, Hamlet met Huckleberry Finn.

With Jeremy Irons, James Earl Jones, Whoopi Goldberg, Matthew Broderick, Nathan Lane and Cheech Marin lending their vocal talents to the enterprise, and with a sheaf of hit tunes (“Circle of Life,” “I Just Can’t Wait to Be King,” “Hakuna Matata” and the Oscar-winning “Can You Feel the Love Tonight”) by Elton John and Tim Rice, The Lion King proved to be one of the seismic smashes of the past 20 years; in real dollars, only Avatar, Titanic and The Phantom Menace have topped it. Yet the film was also the beginning of the end of traditional, hand-drawn animation. Subsequent Disney features like Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dame were more ambitious but less successful at the box office. And a year after The Lion King, along came Pixar’s Toy Story. The first full-length film made on computers showed audiences a new look, technology and attitude. Within a decade, 3-D animation had almost totally replaced 2-D, and The Lion King would find its most lasting popular appeal as a Broadway puppet show.

19. Tangled

Disney’s first CGI feature based on a fairy tale returned the studio to its hallowed beginnings as a spinner of fables about put-upon princesses. From Snow White and Cinderella to Ariel, Beauty, Pocahontas and Mulan, girls were the focal characters who could be expected to come of age, triumph over adversity and, in general, woman up. When Pixar’s John Lasseter took control of Disney’s languishing animation unit, he green-lighted two femme-centric features: 2009’s The Princess and the Frog (a hand-drawn film of spectacular élan and artistry) and this adorable update of the Grimm Brothers’ story of Rapunzel, imprisoned in a high tower by a witch, with the girl’s long hair the witch’s only means of access and egress.

In the new version, directed by Nathan Greno and Byron Howard, the witch Gothel (voiced and sung by Broadway’s Donna Murphy) discovers that the hair of Rapunzel (Mandy Moore) somehow brings eternal youth, or at least chic middle age, to an old witch. She can swan around as long as her victim stays locked up. Gothel could be many modern American parents who think that confining their teens in enforced preadolescence helps them feel younger too. The character design of Disney veteran Glen Keane frees Rapunzel from visual stereotype and gives her poise and spunk. Oh, there’s a Prince Charming (Zachary Levi), but Tangled, like The Princess and the Frog, is a rallying cry for girl power — and an indication that the studio that created the princess-musical animated feature can still give the format vibrant life.

20. Paprika

Anime, the Japanese form of cartooning, has yielded far more animated features in its 40-some-year existence than the rest of the world put together. From this teeming, often dark and astonishingly sophisticated output, Satoshi Kon’s last completed film is one of the most forbidding and beguiling. It’s an R-rated psychological detective story about a machine, the DC Mini, that offers the key to unlock the meaning of dreams — even as animation is, in a way, the key to unlock the feeling of dreams. A police detective hopes to solve a murder by telling his dreams to the sexy Paprika, who is also a staid researcher named Atsuko. They are aided or threatened by the usual sci-fi-noir suspects, but the plot is so complicated, it’s best not to worry about parsing it and just go with the seductively somnambulist flow, which is where the movie finds its true life. Paprika alternates dream with reality, or abruptly fuses the two, until the detective, and the viewer, can’t tell them apart.

Kon, whose earlier films included the sado-thriller Perfect Blue and the movie-crazy Millennium Actress and who died in 2010 at 46 of pancreatic cancer, saw modern media as not linear but oneiric. “Don’t you think that dreams and the Internet are similar?” asks Paprika. “They’re both places where the repressed conscious mind vents.” But the place where the detective will unlock his mystery is a movie palace, the dark cathedral where the communicants’ separate obsessions become one dream on a giant screen. And the most fluid form of movies is animation. Paprika is both an argument for and a demonstration of animation’s power to put us into a state of alert hypnosis. Watch the images that float by, the impulses that pass from the characters to you. You are getting … very … dreamy.

21. Kung Fu Panda

Po (voiced by Jack Black) dreams of martial-arts glory: defeating the legendary Furious Five kung fu masters in mortal combat. When he wakes, though, he’s just a doughy panda who works in the village noodle shop run by his father — who happens to be a goose, but never mind that for now. Po unaccountably is declared the region’s savior and put under the tutelage of the sage Shifu (Dustin Hoffman) — not to battle the Furious Five but to team with them to defeat a Voldemorty beast who’ll be breaking out of prison any day now. Taking as their source the same Hong Kong martial-arts films that inspired both Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and the oaf-becomes-a-hero plot of Stephen Chow’s 2004 Kung Fu Hustle, directors John Stevenson and Mark Osborne devised a master course in cunning visual art and satisfying entertainment: the best and ultimate DreamWorks feature.

If Pixar is the ring bearer of the classic Disney style and uplifting temperament, Jeffrey Katzenberg’s DreamWorks Animation studio is an update of the zany Warner Bros. gestalt: zany, parodic, brimming with pop-culture references. Pixar films might aspire to (and achieve) universal art; DreamWorks reminds the movie industry that “animated feature” is just a fusty phrase for “cartoon.” There’s no question which studio is more influential. DreamWorks’ vaudeville vibe, first paraded in the Shrek series, directly infiltrated animated films from Ice Age to Despicable Me and plenty more. Panda seasons the Katzenberg recipe with a splendid kinetic elegance in the fight scenes — kung-furious panda-monium — and trumps it with the contemplative message that strength and discipline can’t be taught but instead must be discovered within. A wise heart matches the movie’s art.

22. Dr. Seuss’ Horton Hears a Who!

In the Jungle of Nool, something foreign — the nearly infinitesimal planet of Who-ville — lands on a piece of clover, and Horton the elephant (voiced by Jim Carrey) detects cries from the clover speck. He can’t see the little Whos, but he deduces, believes, knows they’re in there; and his caring instinct tells him that they must be protected, against the collective protestations of other jungle creatures. Who-ville’s microscopic mayor (Steve Carell) has the same problem convincing his constituents that some giant unseen creature wants to help them. Ted Geisel’s 1954 book is about belief in what you can’t see, fidelity to a cause that others think is ridiculous and community service to reach an improbable goal. We’re all in this together, Seuss says; everyone’s important. Or, as Horton puts it: “A person’s a person, no matter how small.”

This children’s classic — a plangent plea for kids’ rights — was the source material for a 1970 TV cartoon by the great Warner Bros. animation director Chuck Jones. In the feature version from Blue Sky Studios, directors Jimmy Hayward (a veteran Pixar animator) and Steve Martino elaborated on the TV show’s designs to develop a dense, gorgeously goofy Who-ville — a town whose bright colors and sweetly tilting towers might have been dreamed up on a peyote-munching jag by Antonio Gaudi and Red Grooms. (Who-ville’s daft architectural logic makes a comely contrast to the jungle lushness of Nool.) As the faithful elephant and the cheerfully addled, increasingly desperate mayor, Carrey and Carell do inspired voice work. Though there are enough clever gags to entertain the most demanding media-savvy toddler, Horton remains faithful to the Seuss spirit, 100%. Blue Sky produced the Ice Age franchise, whose first three films have earned nearly $2 billion in movie houses worldwide, and this year’s color-and-comedy riot Rio, but Horton is still the studio’s peak achievement.

23. Yellow Submarine

Intended to take the songs of the Beatles into the medium of animation — and to cash in on the 1960s’ greatest and most profitable pop phenomenon — Yellow Submarine somehow found a sense of humor and sophistication worthy of the Fab Four. To translate the group’s groovy, borderline-psychedelic spirit to pictures, Canadian animator George Dunning assembled a writing team that included Erich Segal, soon to be famous as the author of Love Story, and Roger McGough, Britain’s foremost punster poet. They came up with a free-form, mostly underwater narrative that sent the lads (voiced by soundalikes) swimming backward and forward through the Sea of Time, getting lost in the Sea of Nothing and fighting a vacuum-cleaner beast in the Sea of Monsters, all while fighting off the evil Blue Meanies on their trip to Pepperland.

Some sequences were their own short films (Charles Jenkins created the poignant “Eleanor Rigby” segment), but the thing held together thanks to the hallucinatory opulence of Heinz Edelmann’s design. A G-rated head trip, the movie appealed to kids, their stoned older siblings and their hip parents. As A Hard Day’s Night and Help! had invigorated live-action film a few years before, so Yellow Submarine proved that the Disney style wasn’t the only way for animated features, and the film’s financial success made possible rougher fantasias such as Fantastic Planet (1973) and Heavy Metal (1981). Could the movie, so indelibly a part of its era, speak to ours? Robert Zemeckis thought so: he planned a 3-D version for release in 2012. But after the box-office failure of his animated Mars Needs Moms, his sponsoring studio — Disney — killed the project.

24. Fantastic Mr. Fox

Stop-motion animation is exacting, exhausting work: building puppets, placing them on a miniature stage and moving them one frame at a time — tens of thousands of times. Harder still is bringing insouciant life to this arduous process. That’s what director Wes Anderson and animation director Mark Gustafson managed in this delightful version of the Roald Dahl children’s classic about a dapper, larcenous fox (voiced by George Clooney) who aims to pull off one last, impossible heist. The vibe of Fox and his wife (Meryl Streep) and rebellious son (Jason Schwartzman) is as comically tense as it is in families from earlier films by Anderson (The Royal Tenenbaums) and co-writer Noah Baumbach (The Squid and the Whale). But the brood soon bonds, revealing its humor and humanity, its intrinsic and intoxicating foxiness.

25. Lady and the Tramp

It’s said that when he first watched a rough cut of his studio’s next feature cartoon, Walt Disney absolutely disapproved of one scene: when the Cocker Spaniel Lady and the roguish mutt Tramp dig into a plate of spaghetti on a romantic night and catch ends of the same strand, their faces coming closer to a kiss as they nibble. This, of course, is the moment — played to the strains of Peggy Lee and Sonny Burke’s Neapolitan ballad “Bella Notte” — that immediately entered the DNA of millions of moviegoers and is still cherished more than a half-century later.

Disney’s 15th animated feature, and its first released in CinemaScope, was one of its more modest productions in a decade when the studio had mixed results with its ambitious adaptations of such famous tales as Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan and Sleeping Beauty. Returning to the core Disney values of humor and heart, veteran directors Clyde Geronimo, Hamilton Luske and Wilfred Jackson gave Lady and the Tramp the pedigree of a winner that delights every new generation of children.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com