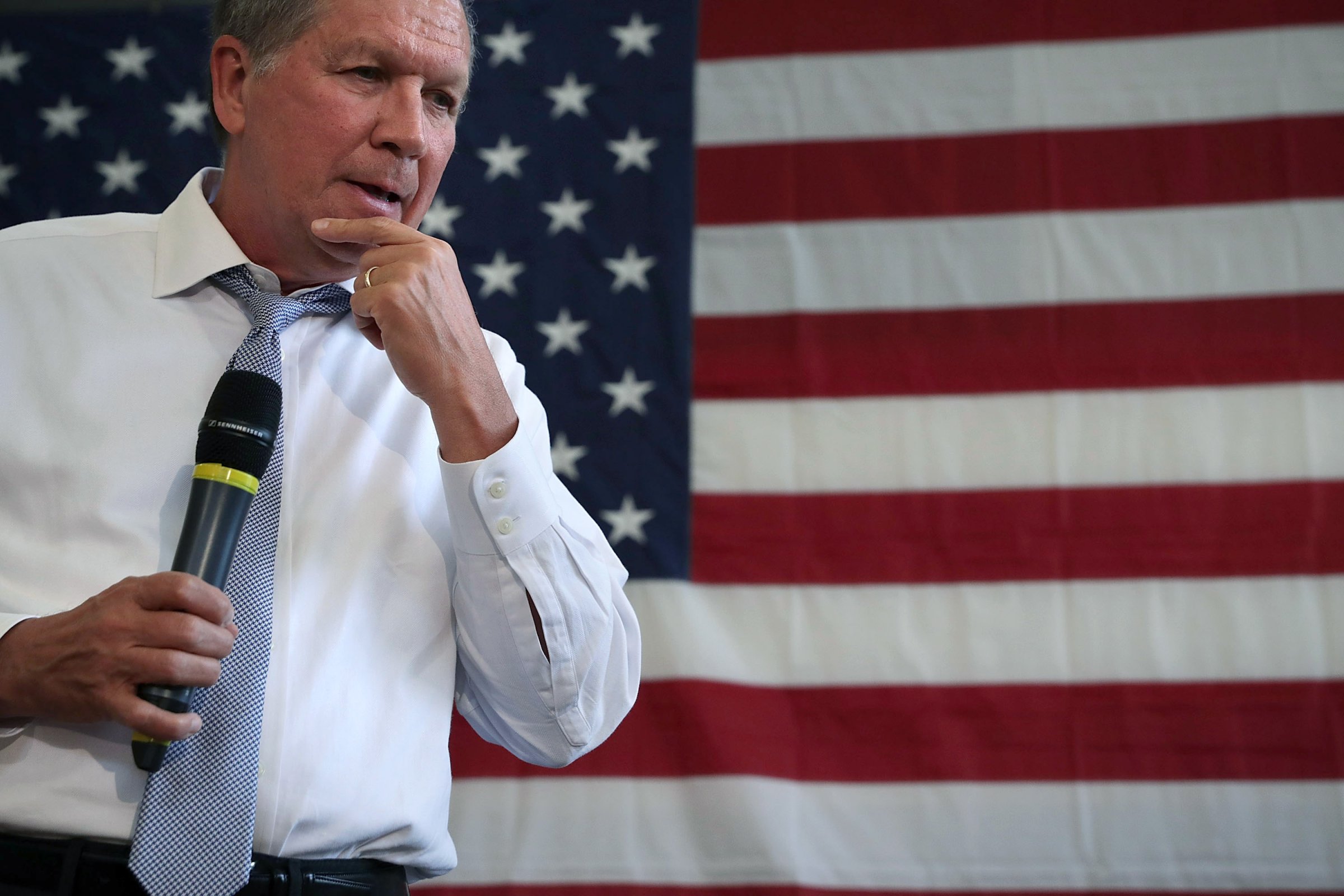

Ohio Governor John Kasich has put the U.S. one step closer to overturning Roe v. Wade. On Dec. 13, he signed a bill banning abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy, with no exceptions for victims of rape or incest. At the same time, Kasich vetoed a bill that would have banned abortions after six weeks and been a near wholesale ban on the procedure, since most women don’t even know they’re pregnant at that stage. The six-week ban, Kasich said, was “clearly contrary to the Supreme Court of the United States’ current rulings on abortion.” The 20-week ban is, of course, also contrary to the Supreme Court’s current rulings on abortion. But for Kasich, the political popularity of 20-week bans overrides their illegality. And, importantly, a 20-week ban may be the vehicle abortion opponents need to impinge upon, or totally end, American women’s access to safe, legal abortion.

In the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the Supreme Court held that in regulating abortion, states have an obligation to balance the interests of women’s health and rights with the interest in preserving and protecting potential life. They outlined a framework, within which abortion had to be generally legal in the first trimester but could be restricted in the second (between 13 and 27 weeks of pregnancy), so long as “the regulation reasonably relates to the preservation and protection of maternal health.” The real turning point, though, was viability — the “compelling” moment when a state “may go so far as to proscribe abortion during that period, except when it is necessary to preserve the life or health of the mother,” the court held.

That trimester framework was largely done away with in the 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey (it was too rigid, the court seemed to think, and not reflective of changing medical realities). While Casey gave states greater leeway to limit abortion access, the viability standard held, with the court affirming “a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion before fetal viability and to obtain it without undue interference from the State.” The majority of the Justices said the state could restrict abortion access previability, but only with laws that did not place an “undue burden” on women seeking the procedure.

Exactly what constitutes an “undue burden” remains vague, defined in Casey only as placing a “substantial obstacle” in front of a woman who wants to end her pregnancy. Requiring a woman to get her husband’s permission for abortion fits the bill, but requiring a teenager to get her parents’ permission does not. States can enact health and safety regulations; they can encourage pregnant women to carry their pregnancies to term; and a later Supreme Court case, Gonzales v. Carhart, even held that the federal government could ban a specific later-term abortion procedure, even though according to Casey, “a State may not prohibit any woman from making the ultimate decision to terminate her pregnancy before viability.” A case from last term, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, sought to clarify the “undue burden” standard, holding that a Texas law passed under the guise of promoting women’s health but with no actual relationship to it — that instead was purposed primarily to make abortions harder to get — did place an undue burden on pre-viability abortion access and was deemed unconstitutional. But even though Texas also has a 20-week abortion ban, that law wasn’t in front of the court.

A 20-week ban prohibits women from making the ultimate decision to terminate a pregnancy before viability. No baby born at 20 weeks or earlier has ever survived. And no one, including proponents of this bill, argues that a 20-week-old fetus is viable.

Revealingly, Ohio law already requires that doctors performing abortions after 20 weeks determine that the fetus isn’t viable, so this new bill is explicitly a ban on pre-viability abortions. This latest ban doesn’t contain an exception for rape or incest survivors. It only allows abortions after 20 weeks if a woman is facing a life-threatening medical emergency that will either kill her or cause “substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function.” Reversible impairment, or destruction of bodily function that isn’t “major,” doesn’t count. The Ohio legislature specifically says that impairment of a woman’s mental health does not qualify as a health exception.

But viability is a difficult concept, at least when you’re trying to legislate it. There is no easily identifiable day or hour or minute when the fetus distinctly crosses the bridge to “viable” and is now guaranteed to live outside the womb. Reproduction is complicated and messy and unpredictable, and every pregnancy, like every fetus and every baby, is different. At 22 weeks, the vast majority of premature babies — more than three of every four — perish. But that means nearly a quarter survive (although always with extreme medical interventions, and they often live with serious health complications). In many states, “viability” is loosely drawn at 24 weeks.

This uncertainty and profound discomfort that comes from not knowing when, exactly, a fetus might survive is why the savvier anti-abortion activists and now Governor Kasich have latched on to later procedures, trying to cast them as both common and morally indefensible. That’s not true — only about 1% of abortions happen after 20 weeks, and women who have late abortions, like women who have early ones, have compelling reasons to end their pregnancies (from “I do not want to be pregnant” to “This will destroy my future plans” to “This could kill me”) — but bans on late abortion are much more popular than banning abortion fully. A full ban on abortion is the goal of every pro-life organization in the country. But they start by encroaching on women’s rights and abortion access in ways that most Americans find acceptable.

This is craven and exploitative. The anti-abortion movement is intentionally opaque about their actual goal — ban all abortions, with no exceptions for rape, incest or a pregnant woman’s health — and pro-life leaders instead insist that they’re worried about things like women’s health or fetal pain. They also send the message that whether or not women have the fundamental right to decide what happens to our own bodies should be decided by majority rule. A foundational American value is that basic rights aren’t up for a vote; a “pro-life” value is that women’s most basic rights can be sold out in the voting booth.

And in shifting the conversation about abortion away from fundamental rights, the anti-abortion movement obscures the complex realities of reproduction. While abortions after the 20-week mark are rare, the women who have them are disproportionately in vulnerable situations: young, poor, depressed, addicted, victims of domestic violence. Many are women who have just gotten very bad news about a very wanted pregnancy — that there’s a problem with the fetus, or that continuing the pregnancy threatens the pregnant women’s health or life. Many are women who are extremely poor, and simply couldn’t get together the money, the childcare and the time off of work earlier on. Many are young and perhaps didn’t know they were pregnant, or spent weeks in denial and fear. Women whose lives have been badly disrupted — women who were raped, or who recently lost a job or a partner — are also more likely to have later abortions. And most women who have later abortions would like to have had earlier procedures, but a series of laws pushed by “pro-life” activists and politicians stand in the way, like restrictions on insurance coverage of abortion and Medicaid funding, restrictions that shutter clinics and make travel farther and more expensive.

The real goal of this law is obvious: it’s not to make women healthier or safer; it’s to push the question to the Supreme Court. Viability is the current standard, and so this law unconstitutional. But because abortions after 20 weeks are so politically unpopular, and because the Supreme Court may be about to be stacked with several staunch right-wing judges under a Trump presidency, abortion-rights advocates worry that a ban like Ohio’s could be the perfect mechanism to either crack the foundation of Roe or knock it down totally. The six-week ban that Kasich rejected was an easy target — so clearly unconstitutional and so politically unpopular it would never even make it to the Court for evaluation. A 20-week ban, though, might just squeak onto the Court’s docket. And that puts pro-choicers in a bind: Challenge the law, and you risk it going up the legal chain with a disastrous result; ignore it, and women in Ohio, and women in many other states with 20-week abortions bans, suffer.

The Ohio ban also offers a scary look at what’s to come under an anti-abortion administration. It punishes doctors who perform abortions after 20 weeks with time in prison. It claims that fetuses feel pain at 20 weeks gestation—a largely unsupported claim about as reliable as the assertion that climate change isn’t real. And it belies a total disregard for women’s health, and the trauma that rape and incest victims have survived.

It would be easy to look at Kasich’s rejection of the six-week ban and his signing of the 20-week one as a sign of his political moderation and reasonableness. Don’t be fooled. The six-week ban was outrageous but obviously wouldn’t hold up, making it an obnoxious waste of time and an insult to women, but not the real threat. The 20-week ban is unconstitutional too, but it’s also a stealth force for undermining Roe — and that makes it so much more dangerous.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com