On New Year’s Eve, Americans may turn on their televisions and have a ball watching a sparkling orb be lowered from a flagpole at the top of One Times Square. The conclusion of the ball drop has become the annual signal that the clock has struck midnight on the first day of the year.

But, while the Times Square tradition dates back to the early 20th century, the idea of using a ball drop to mark time is much more than just a fun holiday activity.

The first “time balls” were built in England, in the Portsmouth harbor in 1829 and at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich in 1833, according to Alexis McCrossen, author of Marking Modern Times: A History of Clocks, Watches, and Other Timekeepers in American Life and professor of history at Southern Methodist University (SMU). (The Greenwich one still exists.) These devices were large enough and high enough to be seen from the harbor or port, and they were designed to help ship captains keep accurate time. For Britain, the maritime power of the day, the question of the time was an important one: at sea, without landmarks to determine longitude and without a stable surface on which to rest a pendulum, it can be hard to tell time precisely. Ship captains would look at the time ball to set their chronometers, a type of clock without a pendulum for seafarers, which had been invented by the carpenter and clockmaker John Harrison.

Though they were designed for mariners, the time balls became major attractions. At around a quarter to noon, large crowds in the area would go outside to get a glimpse of the timekeeper. “These balls, covered in black or red canvas, would be hoisted up to top and at the exact moment of noon, it would float down,” McCrossen says, “and you could check your time keeper.”

By 1844, there were 11 such balls worldwide.

In 1845, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy ordered one built atop the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.—but the American version of the time ball sounds a little bit less organized than its cousins across the pond. After someone gave some kind of oral signal, it would be thrown by hand, land on the Observatory’s dome and roll to the roof below. John Quincy Adams is said to have enjoyed strolling by to watch the time ball fall while he was a Congressman. Between 1845 and around 1902, time balls were erected at locations like San Francisco’s Telegraph Hall, to the Boston State House, as well as less famous towns, like Crete, Neb.

“The vast majority of clocks were put up by government entities to assert their right to control the time,” McCrossen argues.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

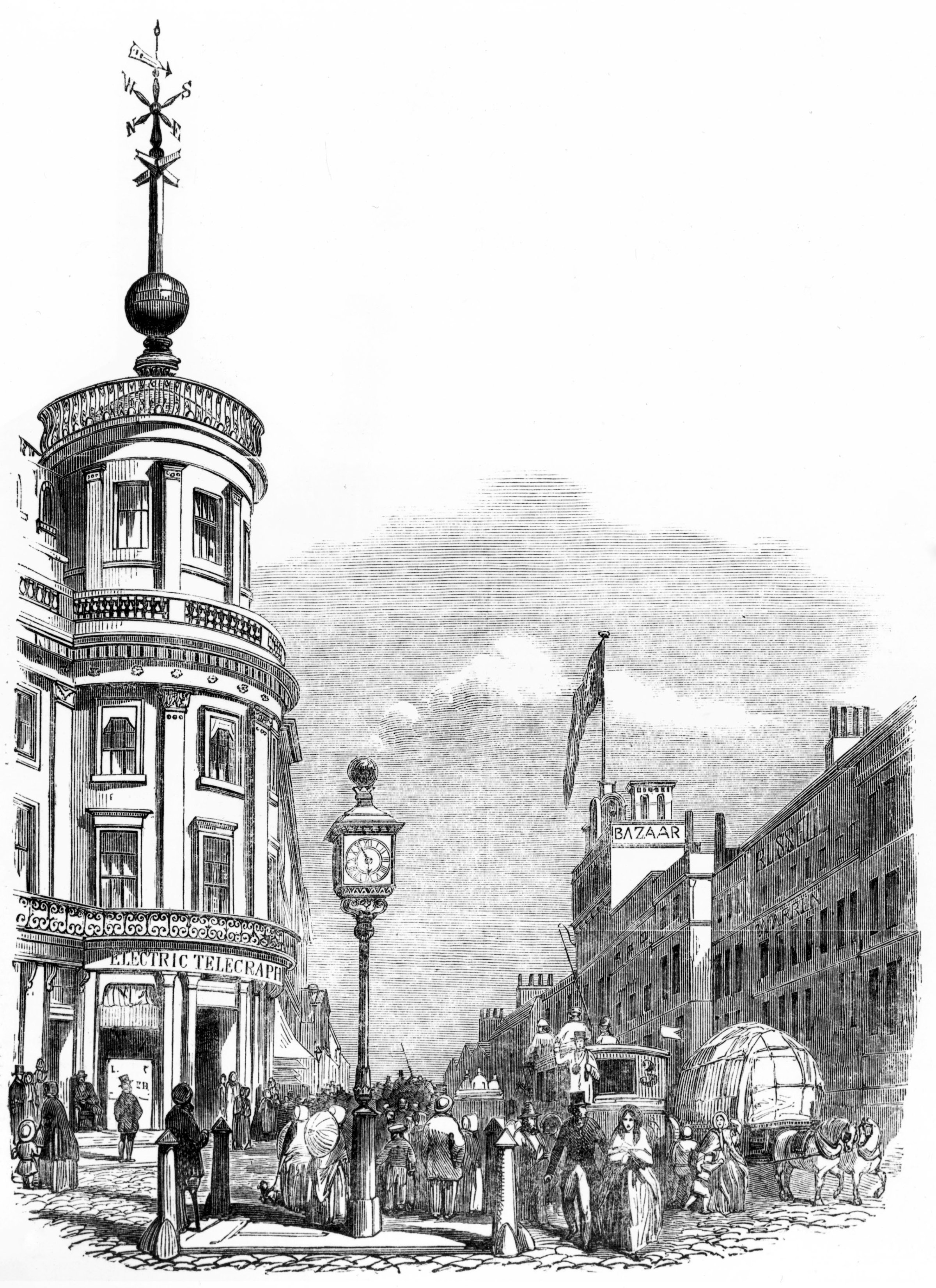

But this method had quite a few kinks. “They were constantly malfunctioning,” says McCrossen. “They were dropping at the wrong time; a notice would be put in the newspaper to indicate the ball was erroneously dropped before or even after noon. They were covered in canvas, so on a windy day or a day when it was raining, the [method] didn’t work.” Eventually, the invention of the telegraph allowed for the transmission of time signals across the wires, which allowed the dropping of a time ball to be somewhat more automated. For example, the time ball built in 1877 on the rooftop of Western Union Telegraph’s New York City headquarters near City Hall received a signal from the U.S. Naval Observatory.

Still, by the late 19th century, the impractical devices were mostly on their way out, or at least reduced to a more decorative or symbolic role.

Once time signals could be sent to people’s clocks through wireless transmissions, fewer and fewer time balls were manufactured, so by 1908, “their time had passed,” McCrossen says (no pun intended).

Yet when a 1907 fireworks ban forced the New York Times to find a new celebratory way to ring in the new year during its annual New Year’s jamboree, the paper’s owner Adolph Ochs, inspired by the Western Union Telegraph’s time ball, arranged for an illuminated seven-hundred-pound iron and wood ball to be lowered from the flagpole of the Times Tower.

“The great shout that went up drowned out the whistles for a minute,” the paper reported at the time. “The vocal power of the welcomers rose above even the horns and the cow bells and the rattles. Above all else came the wild human hullabaloo of noise.”

And that’s one New Year’s tradition that has remained the same, even as our ways of keeping time have changed.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com