Piercing screams swallow up Lewis Hamilton as he enters an amphitheater at the Circuit of the Americas racetrack in Austin on a warm evening in late October. Hundreds of fans have been waiting for hours, pressed against a gate, in hopes of getting something, anything, autographed by the fastest driver on the planet. They shove hats, programs, posters, even cell phones in his direction. One clever devotee places a cap on the tip of his selfie stick, like bait on a rod, and stretches it over the throng. Another name-drops Hamilton’s pet bulldog: “Sign this for Coco!” he shouts. “I love your f-cking dog! You’re my f-cking hero!” Hamilton smiles and signs the hat. Fittingly, Michael Jackson’s “Rock With You” blares over the loudspeakers. Here, the British-born race-car driver is as big as a pop star.

More than 400 million people around the globe watch Formula One races on TV, transfixed by the high-tech cars that resemble sleek fighter jets shooting across the track at more than 200 m.p.h. And Hamilton is the sport’s biggest name, a three-time champ with a raft of famous friends who is swarmed by fans at races from Australia to Azerbaijan, from Monaco to Malaysia.

In the U.S., however, such recognition is rare. Formula One comprises 11 teams with two drivers each, backed by brands like Mercedes, Red Bull and Ferrari. Over some 20 races spread across eight months and five continents, the teams fight for the Constructors’ championship, while each driver vies for the individual title. America hosts just one race per year, the fall Grand Prix in Texas, and Formula One lags in popularity behind homegrown racing circuits like NASCAR, not to mention the NFL, NBA and many other pro and college sports. “So many people I meet in America ask me, ‘What’s Formula One?'” Hamilton says before walking out to his autograph session a day before the Austin race. “What, do you live in a shoe box? Haven’t you at least heard of it?”

For years the American market has vexed Formula One, even as it grew into one of the most popular sports elsewhere in the world. The races are often televised at odd hours and rarely on broadcast networks, making it particularly tough to lure casual viewers. But that may be changing. In September, Liberty Media, the U.S.-based conglomerate controlled by billionaire John Malone, bought Formula One in a deal valued at $8 billion. The purchase has stoked optimism that a domestic ownership group with a range of technology and entertainment businesses in its portfolio will figure out how to make Formula One work in the States. “The U.S. market is important,” says Chase Carey, the former Rupert Murdoch lieutenant whom Liberty installed as Formula One’s new chairman in September. “It’s an area of opportunity for us.”

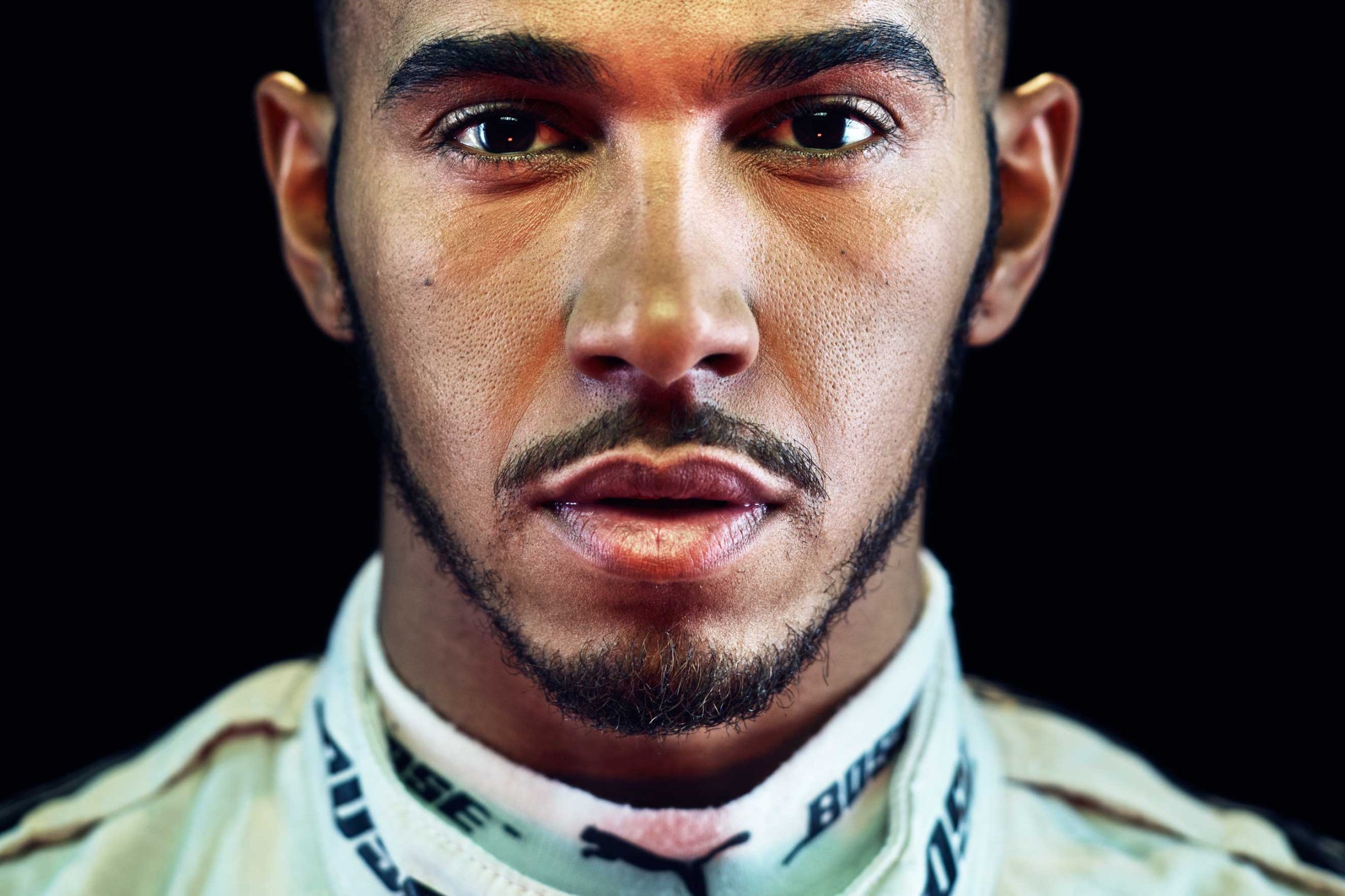

Hamilton will be critical to the effort. The son of mixed-race parents, he became the first black driver in Formula One after growing up in public housing north of London, rather than being groomed in the gilded garages that typically breed championship drivers. Since winning his first title in 2008 at just 23, Hamilton has become as much of a celebrity off the track, a Fashion Week regular whose Instagram feed is filled with shots of him hanging out with Rihanna and Justin Bieber. He’s recorded hip-hop songs and had a role in the latest Call of Duty. “He’s an ambassador for Formula One,” says Christian Horner, head of the rival Red Bull Racing Team. “He takes it to places where you wouldn’t normally see it, particularly in the U.S.”

For an ambassador, Hamilton is not exactly known for diplomacy. The 2016 season played out as a high-stakes rivalry between Hamilton and his Mercedes teammate, Nico Rosberg, with Hamilton repeatedly citing engine trouble for races he lost. On Nov. 27, in the final race of the season in Abu Dhabi, Hamilton defied team orders, slowing the pace in an attempt to thwart Rosberg and keep his own title hopes alive. Hamilton won the race, but Rosberg still beat him out for the world championship—-and then announced his surprise retirement. The hyper-competitive Hamilton was not a model of grace in defeat. “Lewis is Marmite,” says Horner. “People either love him or hate him.”

The loss is fuel for Hamilton, who wants to reclaim a world title in 2017 that he feels he lost in spite of his driving. “It’s been quite a painful couple of weeks,” he tells TIME in a December telephone interview from his home in Monaco. “This is really a time of year when you’re turning, trying to leave the negative behind and take the positive forward. But of course, it will build. The yearning for next year will build.”

Hamilton’s path to the top of auto racing began at age 6, when he started entering–and dominating–remote-control-car races on weekends. His talent landed him on the British children’s show Blue Peter, where he won a race against the host and a bunch of bigger kids. (A YouTube clip shows him raising a tiny, triumphant right arm in victory.) He quickly graduated to go-karts. Hamilton says that the first time he puttered around in a kart, he picked up the braking technique—-hit them late around the corners to maximize speed—-that he still uses today. “I remember that day,” he recalls, “feeling vrrrrrrrrrrrrm.”

Hamilton’s parents split when he was 2. His father Anthony managed his racing career while holding down multiple jobs. They stood out in the U.K.’s all-white karting scene. “We were the scruffy black family,” says Hamilton, whose paternal grandparents are from Grenada. “We had the sh-t equipment, sh-t car and a sh-t trailer.”

Still, Hamilton kept winning, roiling others on the youth racing circuit. “I had parents come up to me and say, ‘You’re not good enough, you should probably quit,'” says Hamilton. “But I just beat your son. What are you talking about?” He recalls racist taunts at the track and says he was picked on at school, where he was one of a handful of black children. About 5 ft. 9 in. and 150 lb. today, Hamilton was never imposing. But at one point, he decided it was time to fight back. “I remember being in the back of the car with my dad. I took my seat belt off, and was like, ‘Can I do karate?'” Hamilton says. “I was 6 years old. I was being bullied and hated it. So I went and did karate and learned how to defend myself.”

At an auto-sports award show in 1995, the 10-year-old Hamilton met Ron Dennis, head of the McLaren racing team, and told him that he wanted to race one of his cars one day. Dennis signed him to McLaren’s young-drivers program, and he flourished. By the age of 21 Hamilton had secured a spot in Formula One, where he turned in one of the greatest rookie seasons ever, losing the championship by a single point.

Hamilton’s instincts and tenacity were evident from the start. Otmar Szafnauer, chief operating officer for the Sahara Force India racing team, recalls watching Hamilton tail McLaren teammate Fernando Alonso, the defending two-time world champ, at the street race in Monaco, whose narrow course makes passing especially difficult. Hamilton finished second behind Alonso, but not before applying heavy pressure. “Someone else in that same situation would say, ‘I have no chance at passing here–it’s Monaco, I’m a rookie, he’s the world champ–just take your second place,'” says Szafnauer. “Not Lewis. That’s what makes him special.”

He won the title in 2008. Two years later, after finishing fifth, Hamilton fired his father as his manager. “It was a pivotal moment, and still the toughest thing I’ve really ever gone through,” he says. “Growing up so close to someone and looking up to someone, and having them move heaven and earth for you every single day, and one day you say, ‘I don’t want you to be a part of it anymore.'”

The following two seasons were rough, with Hamilton matching his career-worst fifth-place finish in 2011. But he says the move was worth the personal fallout. “It was necessary and a very positive thing in terms of moving forward,” Hamilton says. “I’m almost 32 now. I’m not squandering my money. I don’t do drugs. I still have the values on which I was raised.” He switched teams, from McLaren to Mercedes, for the 2013 season before taking the ’14 and ’15 world titles and finishing a close second this season. His net worth, meanwhile, is estimated to be more than $200 million. But the damage remains. Hamilton calls his current relationship with his father “still a work in progress.”

The brash confidence that has enabled Hamilton’s heroics on the track has rubbed many people the wrong way. “There are so many haters, it’s kind of crazy,” says Lindsey Vonn, an Olympic champion skier and a close friend. “When I first met him, I had heard the rumors that he was really arrogant. He’s not even remotely arrogant.” Vonn was part of a small group of boldface pals–including tennis icon Venus Williams, broadcaster Gayle King, actor Christoph Waltz and NASCAR champ Jeff Gordon–who were on hand at the race in Austin. Hamilton often hopscotches the globe between races, appearing at exclusive events with his famous friends. Though he is single now, his longtime relationship with pop star Nicole Scherzinger provided a steady stream of tabloid fodder.

The hobnobbing has riled some members of Formula One’s old guard. “If he was at McLaren,” Dennis, his former boss and mentor, said in 2015, “he wouldn’t be behaving the way he is, because he wouldn’t be allowed to.” Hamilton’s response is the equivalent of pointing to the scoreboard: three titles and 10 race wins this season, including the last four of the year. Besides, he says, his interests in music and fashion prevent him from burning out on the track. “There’s very little that can distract me, really,” Hamilton says. “I’m very much a person of energy, and when you meet someone you naturally feel an energy, good or bad, you know?”

His current boss has no objections. “People out there try to put other people into boxes,” says Toto Wolff, head of Mercedes-Benz Motorsport. “‘This is how you should be, this is how you should behave, this is how you should concentrate on this sport.’ It’s all wrong. If it works for Lewis to fly around the world and go from one fashion show to another, hang out with his friends and do a gig, if that works fine, we should just accept it. We’re much too judgmental.”

From his perch in his company’s swank luxury suite, Heineken marketing executive Gianluca Di Tondo waves to the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders entertaining the crowd before the Austin race. Fighter jets fly over. The University of Texas marching band blares its horns. Di Tondo is betting on this sort of Americana to turbocharge Formula One here. In June, Heineken became a global partner of the circuit, joining brands like Rolex and Emirates. “We are emotionally very attached to this market,” Di Tondo says of the U.S. The pitch is much different here from in Europe, where even nonfans have at least a passing familiarity with the top drivers. “Americans either love it or don’t give a sh-t,” says Di Tondo. Looking out onto a grass hill overlooking the track, he sees room to grow. “That’s where we need the second-tier fans.”

Since Hamilton’s rookie season in 2007, Formula One’s annual global revenue has risen 53%, to $1.83 billion as of July 31, 2016. North and South America combined account for only 10.6% of the haul. But there are signs of growth. Races broadcast on NBCN, a cable sports network, averaged 429,000 viewers this season, the most in 21 years for a single U.S. cable channel showing Formula One. The Austin race, which debuted in 2012, set an attendance record in 2016: almost 270,000 over three days. The number was surely inflated by a Taylor Swift show at the track the night before the race and an Usher concert after—-but many, including Hamilton, think that’s just what Formula One needs.

“The way Formula One is run is not good enough at the moment,” Hamilton says. “The Super Bowl, the events Americans do, the show they put on is so much, so much better. So if you were to mix in a little bit of that template through there, I think we’d be more inviting to the fans.”

Expect Liberty to energize the American efforts. “Given how small Formula One is in the States, it’s a low bar to clear to have some sort of impact,” says Robert Routh, an equities analyst at FBN Securities. Liberty gets a profitable business—-the circuit earned $318 million in operating income in 2015—-while Formula One joins a company that can leverage existing assets to help it grow: Liberty’s QVC network can push Formula One merchandise; SiriusXM can provide Formula One programming; Live Nation can produce entertainment around Formula One events. “We have an enormous opportunity to take this sport to the next level,” says Carey, who helped launch Fox News and Fox Sports before becoming Formula One’s chairman. “In a world where there are more and more choices, there are fewer really distinguishing events.”

Carey sees the chance to brand Formula One as an upscale alternative to other racing circuits. “NASCAR is sort of T-shirts and beer,” he says. “This is the sport of stars and celebrity. It’s champagne.” If so, Hamilton is Dom Pérignon. “We need six of him,” says F1 CEO Bernie Ecclestone, the circuit’s 86-year-old grand poo-bah.

Hamilton calls his tumultuous 2016 season “one of the heaviest on my heart.” He suffered three engine failures, while the cars of his teammate Rosberg rode clean. And then there was the spiteful final race, in which the front-running Hamilton slowed the pace to let other cars catch up to Rosberg in the hopes they would knock him to fourth place—-and allow Hamilton to win the championship. Rosberg salvaged second, and Hamilton was called out for going his own way. “Anarchy doesn’t work within any team or any company,” Mercedes’ Wolff said afterward.

Weeks later, Hamilton says he has no regrets, especially since he remains convinced that his title hopes were felled by his engine. “The team’s job is to provide both drivers with equal opportunity,” he says. “And unfortunately, I didn’t have equal opportunity, because I had failures on our side of the garage. The other side didn’t. So that puts more stress on the importance of myself sucking every ounce of opportunity. At the end, that’s all I could have done. I didn’t do anything dangerous. I didn’t put anyone in harm’s way. I’d do it again. You’re out there to fight.”

Hamilton says he wanted the three-peat “with every blood cell in my body.” After falling just short, he’s desperate to win in 2017. “I’m in a good head space,” he says. “I have a process that I need to take into next year. When I lost the championship, the motivation to want to take it back next year became twofold. I now have twice the desire.” The question is whether America will come along for the ride.

This appears in the December 26, 2016 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com