In her most famous movie, John Huston’s 1952 Moulin Rouge, Zsa Zsa Gabor plays Jean Avril, a chanteuse who enjoys the favors of many men and the habit of lying about her age. “I have been 25 for four years,” she smilingly confides to her friend Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (Jose Ferrer), “and I shall stay there another four. Then I’ll be 27 for a while. I intend to grow old gracefully.” Gabor was 35 at the time, and for the better part of the next six decades she either grew old gracefully or simply ignored the process of degeneration, preserved in the aspic of chic middle age. She was well into her sunset years when a member of Phil Donahue’s TV audience asked how old she was, and Zsa Zsa snapped, “A woman who tells her age tells everything, and I won’t tell it.

Now that this Hungarian glamour girl has finally passed on, after 99 years, we can say it without assaulting a lady’s sensibilities. Zsa Zsa Gabor died Sunday, according to her publicist Edward Lozzi.

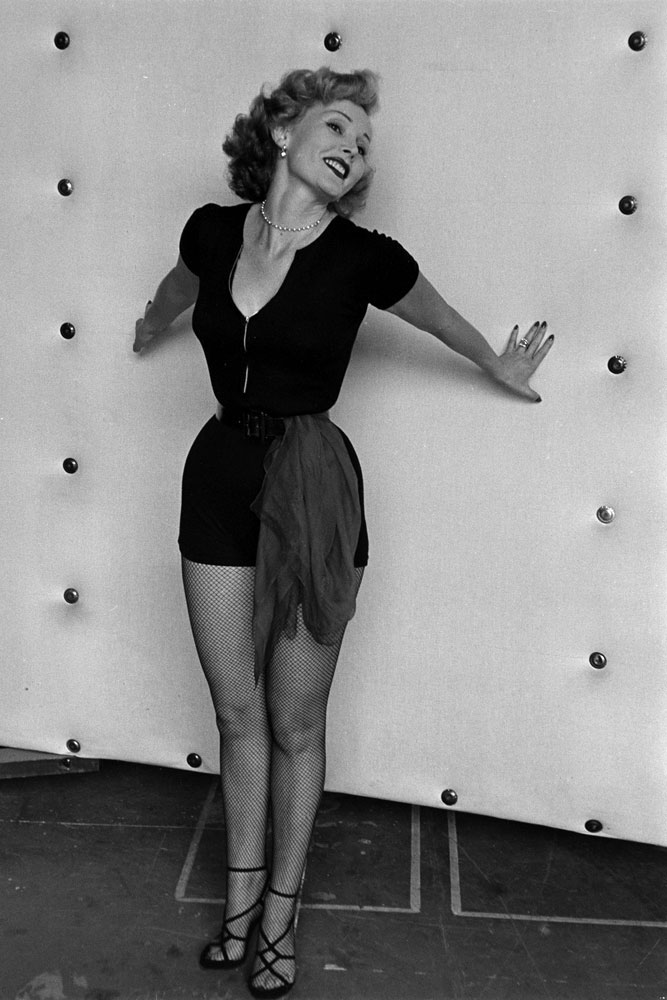

The job description on Gabor’s passport probably said “Actress.” But she was renowned for so much more: the ash-blond hair, the furs and the jewelry, the artfully maintained Hungarian accent, the slyly obvious double entendres, the eight or nine husbands (one marriage was annulled), the three days she served in jail in 1989 after slapping a Beverly Hills cop. Primarily, and almost first in her class, she was famous for being famous—the living embodiment and droll parody of American celebrity. How appropriate, then, that Gabor, through her marriage to hotelier Conrad Hilton, should be the ex-step-great-grandmother of madcap heiress Paris Hilton, a more recent example of the species.

She appeared fitfully in movies, and perennially on American television: one way or another, she spanned virtually the entire history of the medium, from a guest spot with Milton Berle in 1950, through countless talk shows and game shows, to recent Entertainment Tonight reports on her failing health. If she had a vocation, it was raconteuse: the guest on the late-night TV couch who spouted pithy wit, almost always about her very public private life. “I know nothing about sex, because I was always married,” she‚d say; or “Husbands are like fires: they go out when unattended”; or “It’s never as easy to keep your own spouse happy as it is to make someone else’s spouse happy.”

Gabor’s nearly 80 years in the public eye—she was named Miss Hungary of 1936—were less essential than ornamental, and her one significant statuette was a 1958 Golden Globe for Most Glamorous Actress. But why bother being an actress when she could be the Zsa Zsa Gabor?

That couldn’t have been as easy as she made it look. Any old Oscar-winning actress can retreat into her roles; Zsa Zsa lived hers—a full-time job. In the Zsa Zsa Gabor business, she was the creator, the product and the savvy marketer. On the other hand, she needn’t wait for suitable roles; she was this ever-available fiction she called herself. So she’d show up as the mystery guest on What’s My Line in the ’50s (where she had to answer questions in a Frenchy chirp because her voice was one of the world’s most recognizable), or in the ’70s on Laugh-In (“I always said that marriage should be 50-50 proposition — he should be at least 50 years old and have at least 50 million dollars”) or in the ’90s in the movie The Naked Gun 2-1/2, where she swats a police car’s flashing red beacon and stalks away, sputtering, “Ach! This happens every f—ing time when I go shopping.” Zsa Zsa Gabor: it was the punch line to the genial joke she made of her life.

Becoming Zsa Zsa

That life began on Feb. 6, 1917, in Budapest. Her mother Jolie, born Jancsi Tilleman to Jewish parents, had married Vilmos Gabor, a soldier. From this union came three daughters. Magdolna, or Magda, the Zeppo of the group, was first; her movie career seems to comprise exactly one Hungarian film in 1937. Sari—Zsa Zsa—was next, then baby sister Eva, who would eventually be the busiest Gabor actress: for six years she starred in the sitcom Green Acres. Eventually, Jolie was married three times, Eva five and Magda six (including to one of Zsa Zsa’s exes, actor George Sanders). The three women would die within two years of one another in 1995 and 1997. Eva was 76, Magda 78 and Jolie 100.

Discovered by Austrian tenor Richard Tauber, Zsa Zsa took a soubrette role in the operetta The Singing Dream before coming to the U.S. in the 1940s. With little acting experience but carloads of continental élan, she snagged frequent supporting roles in Hollywood movies. Many of them seemed the slightest creative variations on the lady known as Zsa.

The legend is fully formed in Gabor’s first scene in the 1952 comedy We’re Not Married!, which she made just before Moulin Rouge. Playing the pampered wife of oil tycoon Louis Calhern, she’s discovered sitting up in bed, extravagantly coiffed and dolled up in a frilly negligee and teardrop pearl earrings, with a breakfast tray on her lap and a French poodle at her side, munching on the toast and marmalade she’s fed it. Through an elaborate ruse, she frames her faithful husband on an adultery rap to get a divorce and relieve him of his cash, his stocks and his home. (“I am a marvelous housekeeper,” Zsa Zsa later famously said. “Every time I leave a man I keep his house.”) Calhern obediently agrees, until he gets a notice declaring that their marriage was invalid. He lets her read the letter and she, realizing her scheme has backfired, drops to the floor in a faint. The 18-minute skit could be a comic summary of her many marriages, and an inspiration for another of Zsa Zsa aphorism: “You never really know a man until you have divorced him.”

She had just a bit more screen time in Moulin Rouge, carelessly lip-synching to Georges Auric’s song “It’s April Again” (later Americanized into the hit single “Where Is Your Heart”) and looking nearly as fabulous as she thinks she does. Already she had her own couturier; the opening credits proclaim “Miss Gabor’s Costumes Designed and Executed by Schiaparelli.” And already Zsa Zsa’s dialogue sounds tailored for her, as if knowing that her many marriages (she was on her third at the time, to Sanders) will become a source of popular merriment. “What is wrong with me, Henri?” she poutingly asks Lautrec. “Other women find love and happiness. I find only disenchantment.” And the painter replies: “But you find it so often.”

In her next film, the musical drama Lili, Gabor was again the courtesan type who’s dismissive of her more ethereal rival (here, Leslie Caron). After that, her movie appearances became more furtive: bits in the Clyde Beatty Three Ring Circus, Sanders‚ Death of a Scoundrel and Orson Welles‚ Touch of Evil. Even in the ’50s now she was illustrious enough to play characters based on herself. She’d drop in, impart some womanly wisdom and split. In the 1962 comedy Boys’ Night Out, where her character is identified only as Boss‚ Girl Friend, she says, “Dahling, a girl can’t make a success on instincts alone.” Gabor had the instincts for show business but not the technique for genuine movie acting. Most of her performances were basically posing; every film was a photo shoot.

The picture she’ll be remembered for, pity, is the 1958 Queen from Outer Space, a low-budget fantasy without the naïve energy or idiot inspiration to be a camp classic. When American astronauts make the first trip to Venus, they discover a planet populated entirely by fabulous babes—an extraterrestrial Playboy Club. Zsa Zsa is not even the planet’s evil queen here (that’s Laurie Mitchell); she is Talleah, the handmaiden who helps the Earth dudes get back home. Coddled by the film’s costume designer, with a new cocktail dress or evening gown for every scene, Zsa Zsa was tortured by screenwriter Charles Beaumont, who handed her many lines that tested her Lady Dracula pronunciation: “Ve have no life here vithout love” and “It vas a terrible var. Ve fought vis veapons of great power.” Masochists can find the whole movie on YouTube.

LIFE With Zsa Zsa Gabor: Rare Photos, 1951

![A 25-carat glow is shed by her ring as Zsa Zsa Gabor takes daughter [Francesca, by hotel magnate Conrad Hilton] walking at their Bel Air home.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/150127-zsa-zsa-gabor-01.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Doing Zsa Zsa

She made a few more movies (a tiny part as the title character in Picture Mommy Dead) and did comic-vamps on ’60s TV series (Minerva on Batman, a rich bitch who wants to buy Gilligan’s Island). But since the role she played best was herself, Zsa Zsa found her most congenial stage on variety shows, game shows and talk shows. She’d banter and appear in skits with Bob Hope, Dinah Shore, Dean Martin. On Hollywood Squares she was asked, “Which of the following places consumes the most Cheez Whiz?” and replied, “Vat is a Cheez Viz, dahling?” She was a favorite guest of Jack Paar, Johnny Carson, Merv Griffin, Mike Douglas, Joey Bishop, Regis Philbin, David Frost, Pat Sajak, Garry Shandling, Rosie O’Donnell, Howard Stern (she kissed him) and David Letterman.

Nobody knew the job of talk-show couch-sitter better than Zsa Zsa: keep it light and funny, promote yourself. She’d hawk one of the three books she “wrote”—My Story in 1961, the 1970 How to Catch a Man, How to Keep a Man, How to Get Rid of a Man (“Johnny Carson gave me that title,” she told Letterman) and One Life Is Not Enough in 1992—or spout a few Zsa Zsa aphorisms (“The only place men want depth in a woman is in her décolletage.”). On a ’90s show, Letterman took her on a culinary tour of L.A.’s fast-food drive-ins, at one point applying the Heimlich maneuver to the game Gabor. Cruising in to one joint, he asked the kid at the window, “Ask her how old she is. Y’ever see that Jurassic Park movie? She used to have those animals as pets.”

She kept husbands, too, but not for long. Depending on whether you count the one that was annulled, Gabor either beat or tied the eight marriages of Mickey Rooney, Elizabeth Taylor, Artie Shaw and Larry King. Her spouses, from the top: 1. Burhan Asaf Belge (Turkish politician), four years; 2. Conrad Hilton, five years; 3. Sanders, five years, to the day; 4. Herbert Hutner (stockbroker), 3-1/2 years; 5. Joshua Cosden, Jr., 19 months; 6. Jack Ryan (Barbie Doll designer), 19 months; 7. Michael O’Hara (her lawyer when she divorced Ryan), 6-1/2 years; 8. Felipe de Alba (attorney and actor), one day, annulled; 9. Frederic Prinz von Anhalt, 24 years, until her death. Except for her last, and lasting marriage, these can’t all have been fulfilling — she claimed that her one child, daughter Francesca Hilton, was the result of Conrad’s raping her — but they provided her with talk-show gag lines. “Conrad Hilton was very generous to me in the divorce settlement,” she once said. “He gave me 5000 Gideon Bibles.”

So successfully did she push her Magyar mystique that soon other people began doing her work: they talked about her. Dion DiMucci’s 1963 top-10 single “Donna the Prima Donna” included the couplet “She wants to be just like Zsa Zsa Gabor, / Even though she’s the girl next door.” And on a late-’80s episode of The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson, Jane Fonda asked Carson if one Zsa Zsa anecdote was true: “My son said she was on Johnny Carson one night; she came in here with a cat on her lap, and she said, ‘Do you want to pet my pussy?‚’ And you said, ‘I’d love to if you’d remove that damn cat.'” (Carson sheepishly replied that, if the encounter had happened, he’d have remembered it.)

Some actors are paid millions to be in movies; Gabor, like any other talk-show guest, received the Screen Actors Guild minimum of a few hundred dollars per appearance. And though her husbands footed many of her bills, they too had hard times: she and von Anhalt lost a reported $10 million invested with financier-thief Bernie Madoff. So Zsa Zsa did TV commercials: for Wheel of Fortune (“They can take away my husbands, they can take away my driver’s license — but, dahling, don’t touch my Veal [Wheel]”) and for the VW Beetle Le Grand Bug (where, while rehearsing the spot in the tiny car, she famously exploded, “I can’t do this goddam f—ing commercial. I have claustrophobia, I don’t vish to vork like this!”). She also starred in her own 1993 workout video, It’s Simple Darling, with two beefy guys doing all the work, and Zsa Zsa chatting blithely away: “He wants me on my knees. I never kneel before a man.”

Leaving Zsa Zsa

“I don’t have a plastic surgeon!” she exclaimed on the Donahue show. In that case, she was a miracle of genetics, expert pampering and the workout routine many men applied to her. Her legend was also remarkably well preserved; she carried it from Hungarian girlhood to the years before her death. On July 17, 2010, in an almost poetically appropriate injury, she’d fallen out of bed and was rushed to the hospital. Her husband said she was in a coma; her daughter denied it. Gabor left the hospital less than a month later but returned two days after that. Doctors removed blood clots but she refused further, saying she wanted to “spend her final days at home.”

Those words recall the last scene of Moulin Rouge, in which Toulouse-Lautrec, dying alone in his bedroom, conjures up images of the people he had painted. One of these is Gabor’s Jane Avril, whose specter sweeps into the room and bubbles, “Henri, my dear, we just heard you were dying. We simply had to say goodbye. It was divine knowing you. There is the most beautiful creature waiting for me at Maxim.” She blows a kiss, trills, “Goodbye, Henri, goodbye!” and vanishes.

Mademoiselle Gabor, you silly delight, we can’t say for sure that you’re about to meet a most beautiful creature; but we’re grateful for the pleasure you gave, and the fun you conveyed in being that clever little fiction known as Zsa Zsa. It was divine knowing you.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com