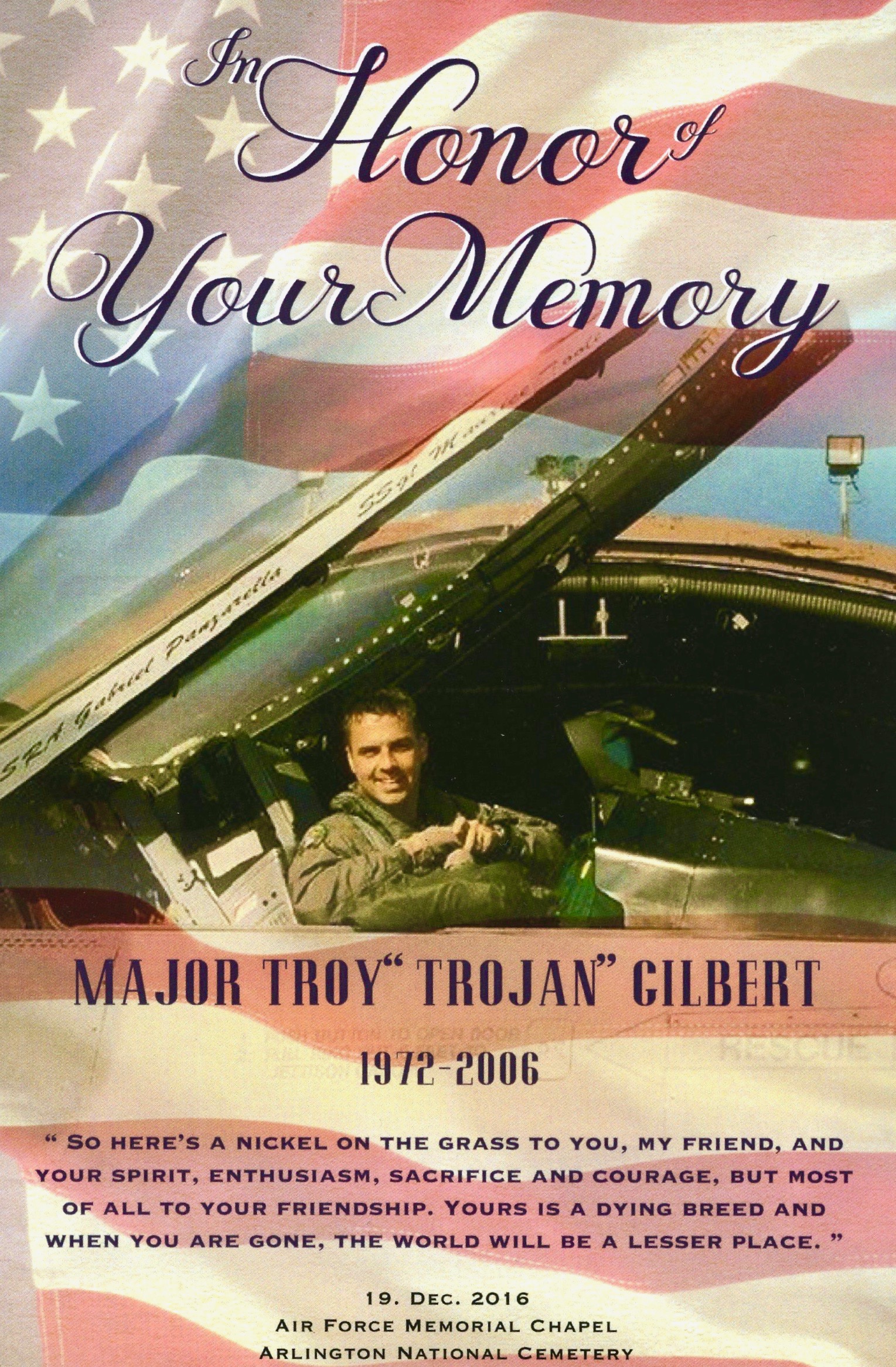

Air Force Major Troy Gilbert was laid to rest, finally and completely, at Arlington National Cemetery on Monday.

He’d already been buried twice, in bits and pieces, in 2006 and 2013. Monday’s interment made him the only person known to Arlington ever to be buried in the nation’s most hallowed ground three times.

Once again, a lone bugler played taps. That mournful sound had rolled across Arlington’s Section 60 for Major Gilbert twice before, plaintively but tentatively. Gilbert’s grave has remained in the same place for 10 years, but the neighborhood has changed. “When we first went there, it was just empty beyond his,” recalls Ginger Gilbert Ravella, his widow. “Sadly, there are now many more graves there.”

Monday, after a long decade of waiting, there was a blessed finality as those fading notes wafted from the part of Arlington where many of those killed in Iraq and Afghanistan now rest alongside him. Country singer Lee Brice performed a pair of songs dedicated to Gilbert during the service.

The 400 gathered included waves of Air Force blue, fighting with a cerulean sky. The poinsettias were close, but not quite, the same hue of the red stripes of the U.S. flag draped over his casket. And the wreaths inside the Fort Myer Memorial Chapel just outside Arlington echoed their deep green on nearly a quarter-million wreaths placed on white tombstones nearby.

Gilbert was 34 when he was killed on Nov. 27, 2006. His F-16 crashed as he strafed al Qaeda-linked trucks threatening U.S. soldiers on the ground 20 miles northwest of Baghdad. Scraps of his remains were recovered at the scene within hours, and bone fragments were returned to the U.S. in 2013.

For a decade, his family longed for the return of the missing 99% of their son, husband and father. Iraqi militants had snatched his body following the crash, and moved it among themselves. “He was like a trophy, going from tribal leader to tribal leader,” says his father Ron Gilbert, a retired Air Force senior master sergeant.

But a U.S. special-operations raid finally got him back in September. “Brave Americans doggedly pursued the return of Troy Gilbert,” says Robin Rand, a four-star Air Force general. Rand commanded Gilbert, both stateside and on his last assignment, and isn’t interested in knowing all the particulars about the still-secret raid that returned him to U.S. soil on Oct. 3. “Troy’s home, and, for me, that’s enough.”

The family delayed Gilbert’s final service so that his five children, ages 10 (his twin daughters were six months old when their father last saw them) to 19, could attend without disrupting school. “The fact that his body was overseas was not something I would have chosen,” says son Boston, now a 19-year-old freshman at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “Obviously, I wanted him back.”

It took years for Gilbert’s widow, Ginger, to tell all the couple’s children what had happened to their father. “I remember walking behind the caisson with my little kids and feeling like, ‘I know he’s not in there,’” Ginger recalls of his first funeral, on Dec. 11, 2006. “Everybody knew he wasn’t in there, except my children. I mean, there was one small, tiny, tiny little piece, but I didn’t want them to know, because how do you explain that to your little kids?” Ginger married Jim Ravella, a retired F-15 pilot who lost his wife to breast cancer, in 2008.

When Gilbert’s toe bones were recovered in 2013, the twin daughters—by now 7 years old—were flummoxed by the need to return to Arlington for a second service for their father. “They were like, ‘What? We’ve already buried him,’” their mother remembers. “You can imagine what it’s like for children to bury their father three times.”

It’s not easy for parents, either. “We went down to San Antonio the day he left to see him off,” Ron says of that day in September 2006 when his son left for Iraq. “He told us, ‘Mom and Dad—don’t worry. I’ll be all right. I’ll be back.’ And those were his last words to us.”

Nothing, of course, can ease the family’s pain at Troy’s loss. But there is the consolation of knowing, at long last, that he is now where he belongs. “Thank God, this is our very last one,” Kaye Gilbert says of her only son’s final funeral. “It made me so happy to learn he was coming home.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com