The greatest contribution Barack Obama can make in his post-Presidency is to continue to make the case he expounded in his interview with Jeffrey Goldberg in The Atlantic in April 2016: for seriously reducing the damaging, unaffordable, counterproductive global overreach that is driven by the belief that it is America’s responsibility to maintain order in the world.

As Obama points out, the first problem with this is that it sets an unachievable goal. Fortunately, as he goes on to note, while our inability to bring stable governance to every part of the globe falls short of the ideal, it does not always—or even most often—inflict harm on us, much less threaten our national security. Finally, to the argument that, if the goal of an American-enforced stability is morally preferable to the violence and chaos that will occur in its absence, there is no harm in trying, Obama draws the clear lesson from recent history: Yes, there is.

There are examples where the clearly defined use of force for a very limited purpose has worked. Bill Clinton in the former Yugoslavia and George H. W. Bush in Kuwait—about which I now concede that I was wrong—are two. But they succeeded because they were limited. They did not try to remake societies or to build better nations from the inside. They freed stable, albeit very imperfect, ones from outside oppression.

The coming to power in the George W. Bush administration of advocates of a much broader, deeper, intrusive role in the affairs of others demonstrated how deep the harm could be—both to our country and to the very notion of global stability they claimed to be furthering.

Obama’s effort to bring us back to a more appropriate approach to the world has of course been complicated by the serious problems he inherited—and in one case, Libya, by his own imperfect execution. But the basic direction of his effort—to withdraw from overexposure and to avoid new quagmires—is clear.

Most encouraging, it is already far more acceptable to the American public than many thought that it would be. A year ago, there was close to a consensus Republican position that Obama and the Democrats were politically vulnerable for having been insufficiently unassertive militarily. And then came the two surprisingly popular insurgencies that included, with some differences, the insistence that America play a smaller role. Bernie Sanders’ vote against the Iraq War was an important part of his campaign. Even more telling was Donald Trump’s inaccurate claim that he had also been opposed to it, and even with his unexplained, incoherent assertion that he would destroy ISIS, his general foreign policy approach is completely counter to the stop-leading-from-behind line that only recently was the dominant Republican view.

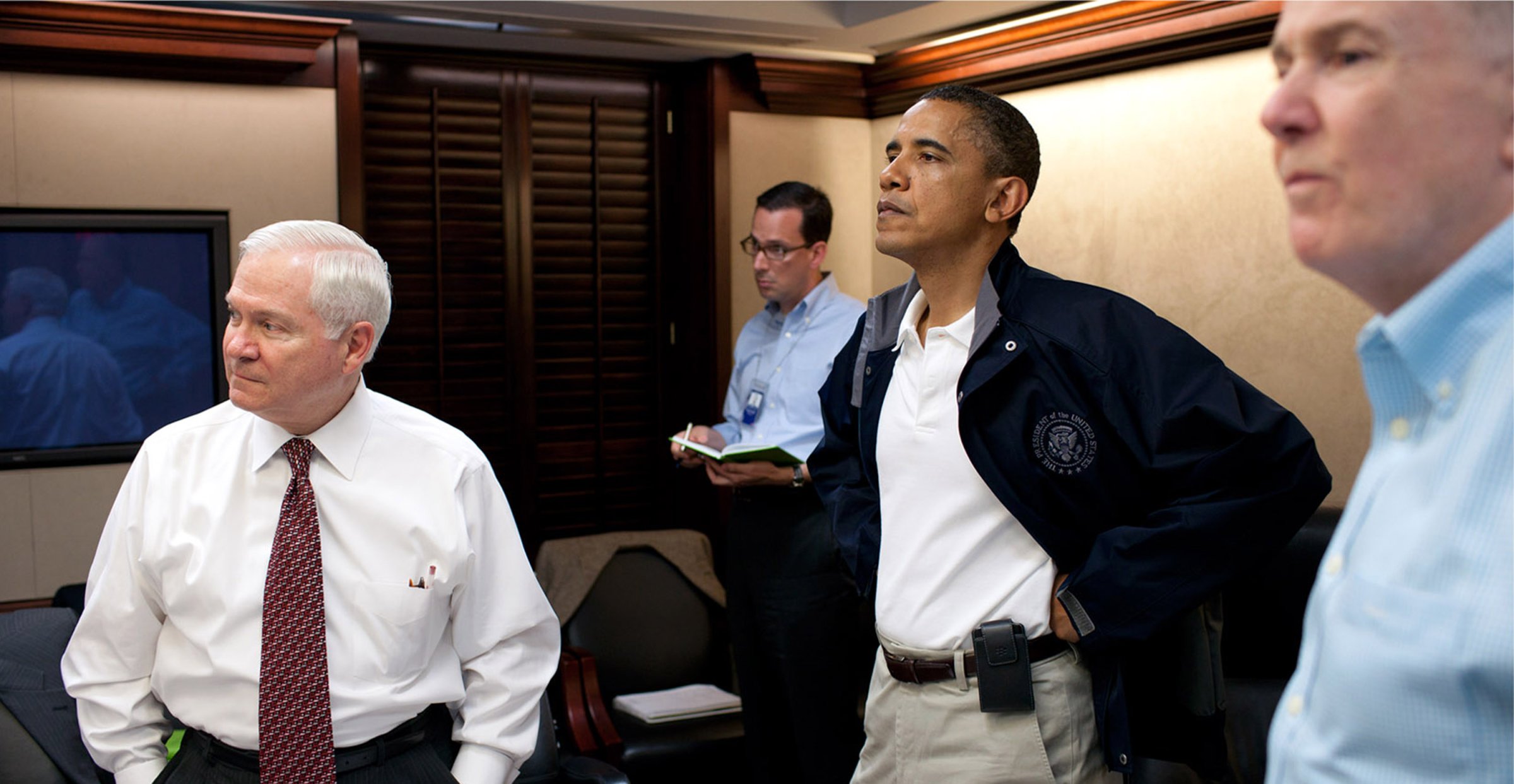

This puts Obama in the ideal position to make his case. The public is ready to hear it. No one can seek to refute him by claiming that he doesn’t know the real story. He has the credibility of having directed the killing of Bin Laden and other terrorist leaders. And since he can never again run for President, and is unlikely to take John Quincy Adams as his role model and run for Congress, he can make the case wholly free from any argument that it is politically motivated.

Tweet your own suggestions of what President Obama should do after he leaves office with #AfterJanuary, and read other suggestions from leaders here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com