When Aditi Gupta got her first period, aged 12, everyone told her to keep it a secret. Even her closest family members in her native India couldn’t know. She was forbidden from worshipping at her temple while she was menstruating, and instead of sanitary products used rags that caused her to have rashes. “When girls [in India] get their periods, they are considered impure for those 7 days,” Gupta tells TIME. “That is how I grew up, seeing myself as impure. That sense of shame was instilled in me from a very young age.”

She is not alone. In a world where over 5,000 euphemisms are used to describe it, menstruation is one of the oldest and most far-reaching taboos. Especially in India and across South Asia, the reluctance to speak about periods is widespread, resulting in worryingly low education and awareness – particularly among the demographic of adolescent girls, of whom India has some 120 million. A recent study for Menstrual Hygiene Day reported that 1 out of 3 schoolgirls across South Asia were not aware of periods before experiencing one for the first time, and only 2.5% of the same group knew that menstrual blood came from the uterus. Now, a new generation of social entrepreneurs across the region are looking to break the centuries old taboo, and Gupta is one of those leading the way.

The 32-year-old engineering graduate from Jharkhand, eastern India, refers to Glora Steinem’s essay ‘If Men Could Menstruate‘, in which Steinem imagines a world where menstruation would be celebrated – but only if it were a male body process. “I just thought ‘oh my god, this is the answer to every question I’ve ever had,’” Gupta says. “We are taught that ‘vagina’ is a shameful word, and a censored word. If the word is censored, that body part becomes censored.”

Gupta only launched Menstrupedia four years ago, but the platform has already made a significant contribution to opening up the conversation on menstruation. The organisation aims to promote awareness and act as a guide to periods for girls and women, using a website, social media including a YouTube channel, and a comic book. With over 37,000 likes on Facebook, a forum welcoming contributors to openly voice their thoughts and a publication that reaches 30,000 girls across India, Menstrupedia has had a big impact since its creation, and Gupta has bigger plans for its future.

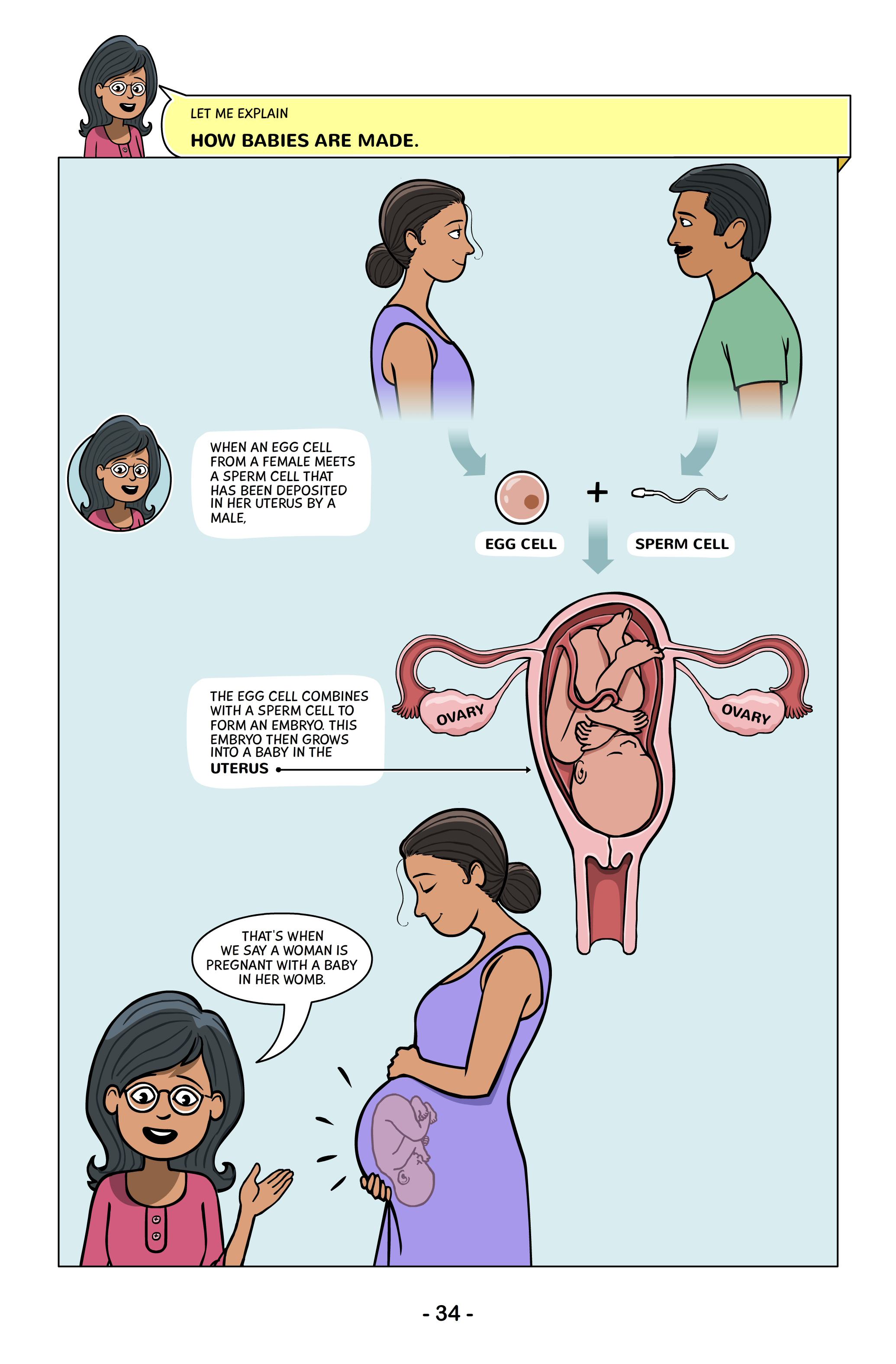

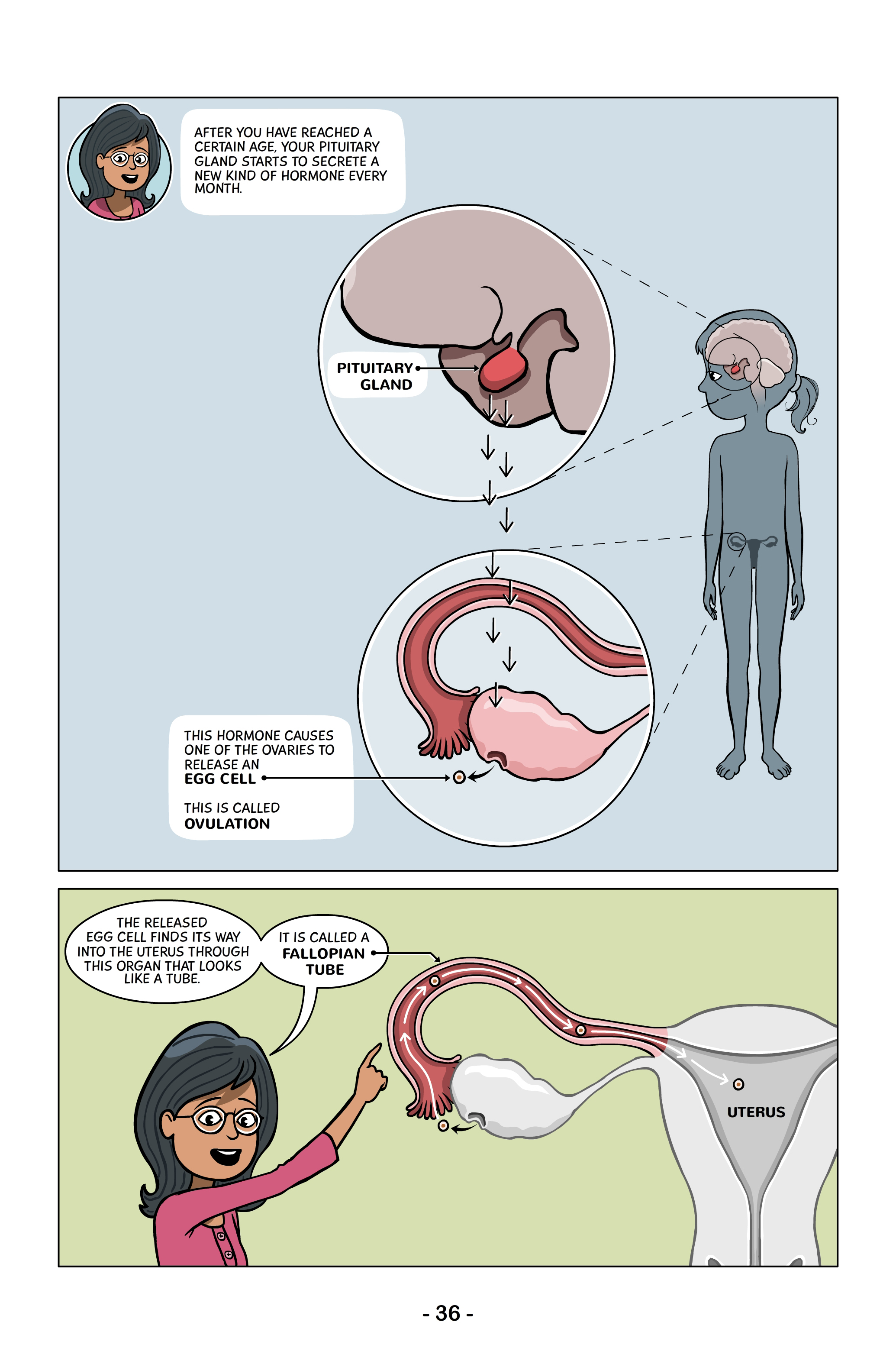

While studying at the National Institute of Design in Gujarat, Gupta met both her now-husband and business partner, Tuhin Paul. In 2013, the pair launched a crowdfunding campaign to produce an illustrated comic book both for girls to read and for teachers and parents to use as an educational resource. “We decided that we would show the female anatomy properly in the comic, because we just realised how many misperceptions there were after launching our website,” says Gupta.

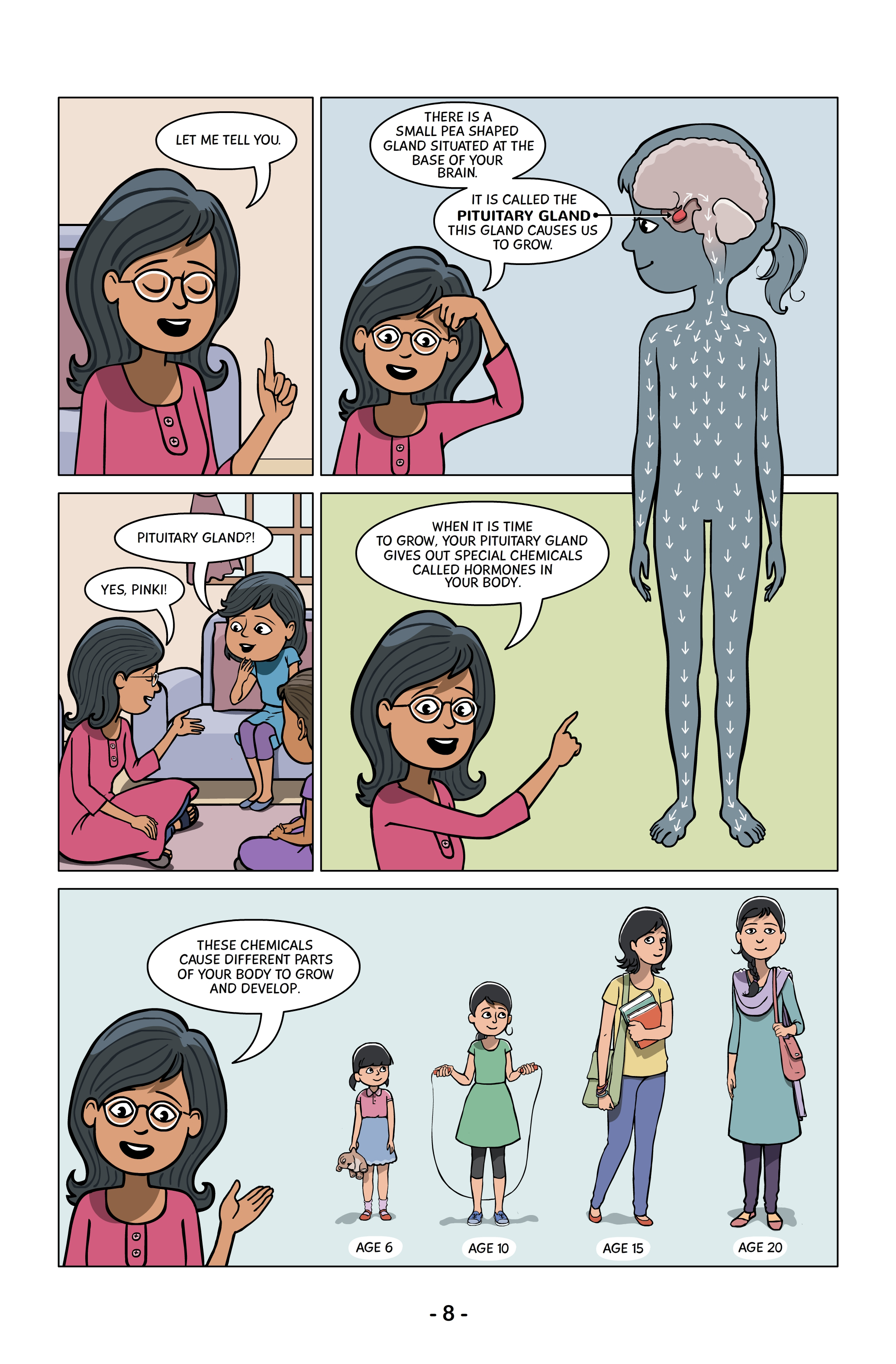

Menstrupedia Comic is the result: a colorful, fun and accessible guide to menstruation, following the journey of three young girls and their experiences with periods. Each character represents a stage of adolescence – girls who haven’t started their period yet and want to learn more about them; girls who have just started their period and want advice on how to prepare for them; and girls who have had periods for some time and might be curious about the myths surrounding them.

The comic, aimed at girls aged nine and above, has since been integrated into the curriculum of 70 schools across India and translated into 11 languages. “Myth breaking and period positivity are our strategies, and we wanted to make it a comic book because it’s inclusive,” Gupta says, referring to the book’s storylines that were adapted from real life experiences. “We wanted to do it in a positive and matter-of-fact way to debunk misconceptions, and so that parents and teachers would be comfortable using it. Girls can read it and say ‘oh, this happened to me too!’” Both the online and comic book content has been reviewed by medical professionals to ensure its accuracy, an important consideration given that 88% of girls and women in India who menstruate use unsafe materials.

Judging from an increase in campaigns concentrated on breaking the taboo, there have been positive changes in recent years. An estimated 1 in 5 girls in India drop out of school due to menstruation and a lack of toilets. Prime Minister Narendra Modi was praised for addressing these pressing problems in his introduction to the Clean India campaign in 2014, where he advocated for all schools in the country to have separate toilets for girls. Other regional start-ups have sprung into action, including online sanitary products shop Those5Days, design-focused Saral Designs, whose engineers have designed a sanitary towel vending machine, and social enterprise Binti Period, which creates community projects enabling women to produce sanitary towels sustainably.

The stigma was also openly addressed last year by Whisper, a sanitary towel manufacturer, in an award-winning campaign called Touch the Pickle. A key social convention in India prevents girls who are menstruating from touching popular preserved foods, such as pickles, because of the belief that the food will spoil. Whisper’s advert depicted girls and women actively breaking that taboo. “That was part of Menstrupedia’s contribution to the corporate world,” Gupta says, “where we encouraged companies to change their strategy of selling menstruation and to do so in a more positive way.” Whisper approached Gupta and Paul about buying advertising space in the Menstrupedia Comic and became a partner before the book was even created.

Gupta now wants to take Menstrupedia beyond India’s shores. “This is only the beginning of our work. We want to produce the comic for all South Asian countries, and we want to do it for African countries too. The amount of international orders we get makes us realise the taboo is everywhere,” Gupta says. “Our plan is to build an educational infrastructure, not only for girls but for everybody, to talk about periods in a friendly, free way. I know it’s going to take decades, but eventually, I want to raise a generation of girls who are period positive when they become mothers. When they raise their own girls, period taboos would just vanish from that generation – they wouldn’t even know such a taboo existed.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com