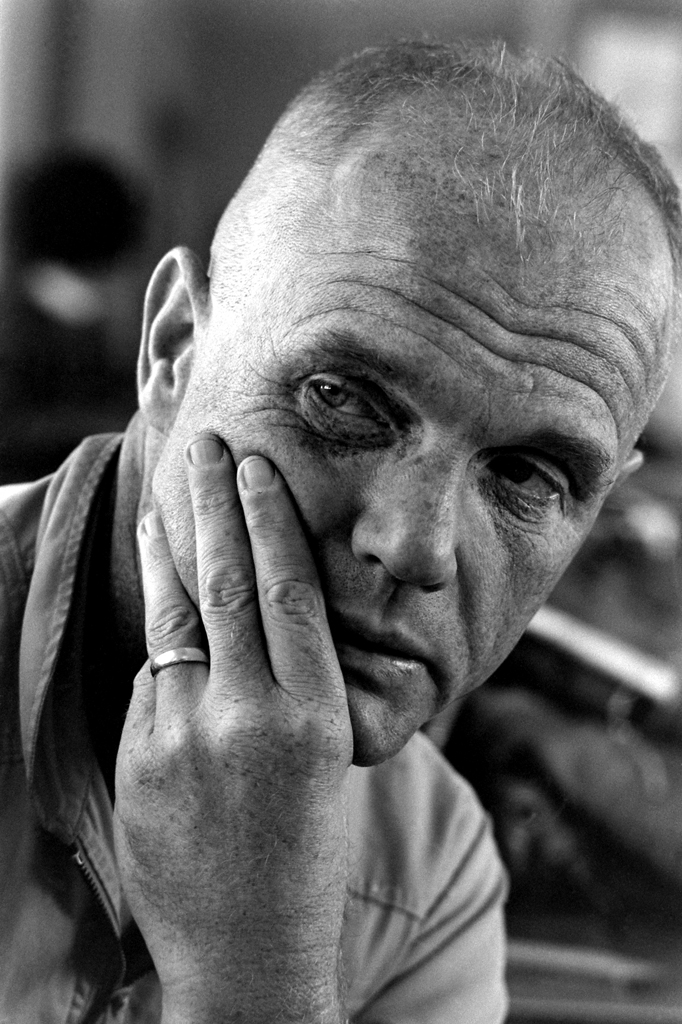

There weren’t a lot of silly pictures taken of John Glenn—mostly because Glenn just didn’t do silly. He did happy, of course. You don’t get the crinkles he had around his sea blue eyes simply because you’ve got the fair, thin skin of the redhead that he was. But if the happy was there, the silly wasn’t.

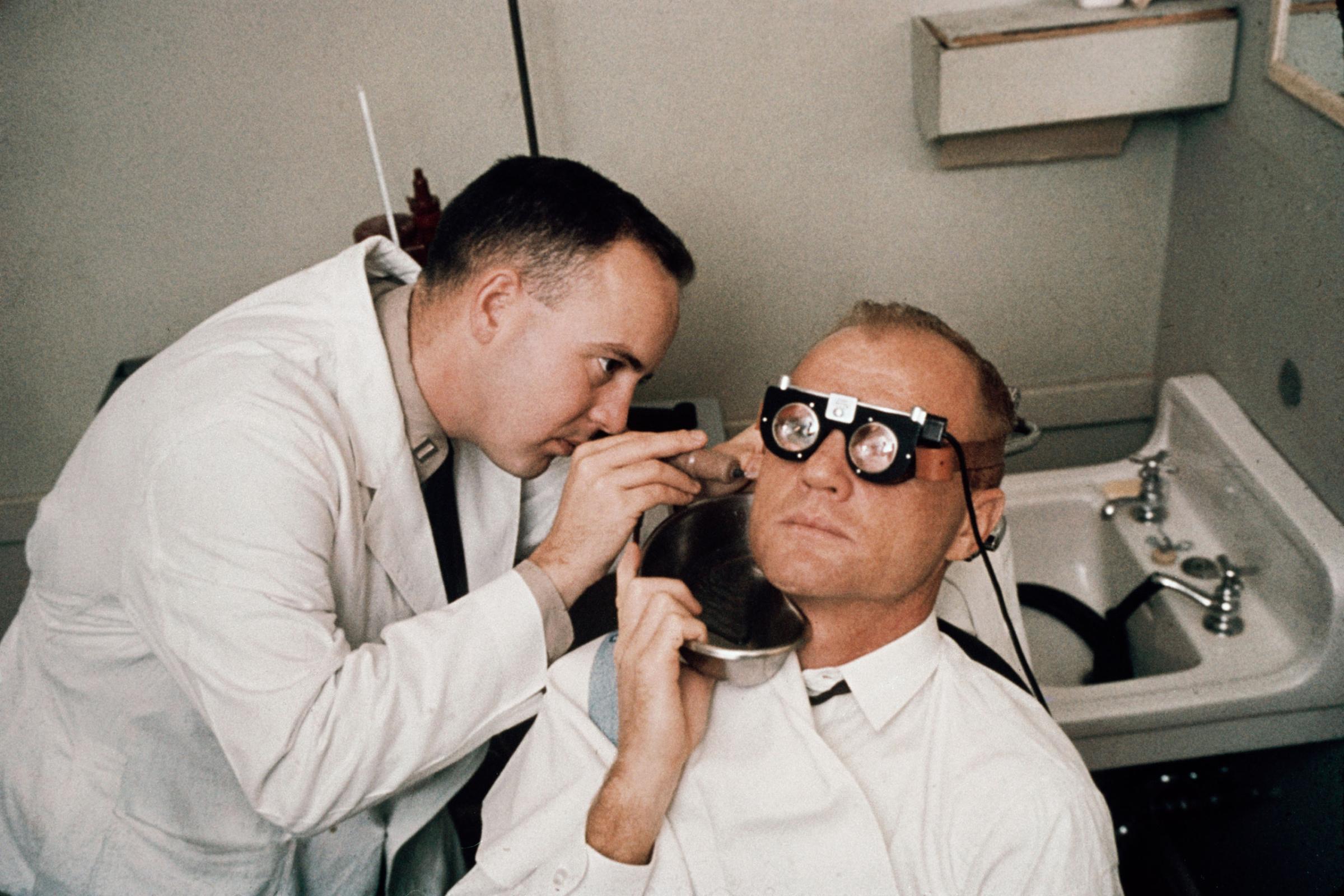

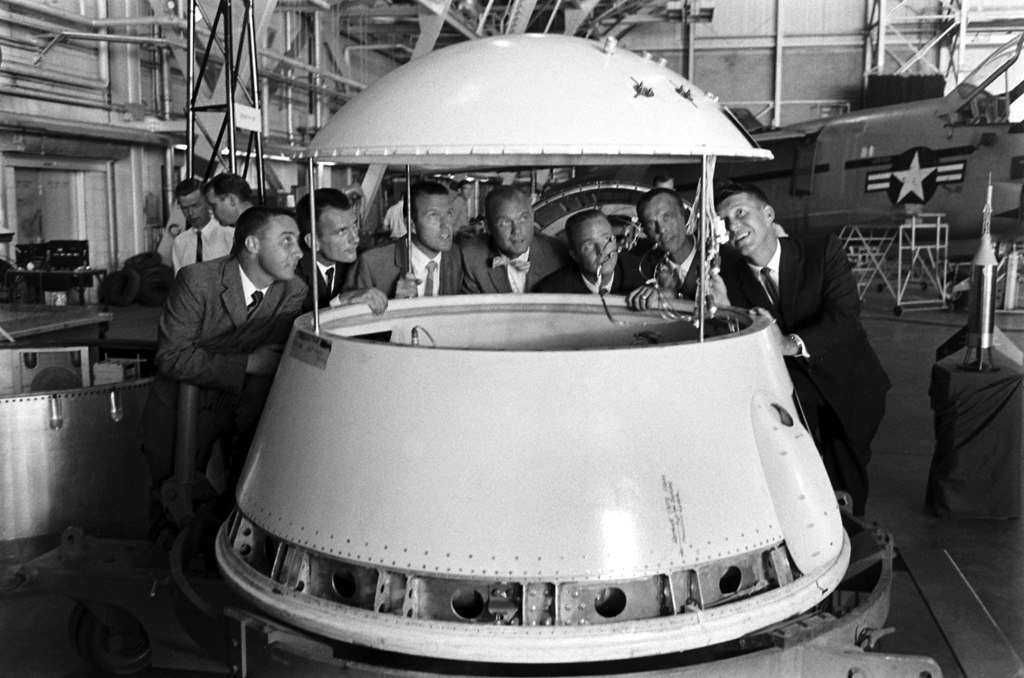

Still, in 1959, when Glenn was announced as one of the original seven NASA astronauts, he knew that he’d have to abide a lot of regrettable silliness—usually at the hands of the space agency and media photographers, who would demand all manner of dreamed-up poses of the deeply American family men the astronauts were intended to be doing deeply American family things.

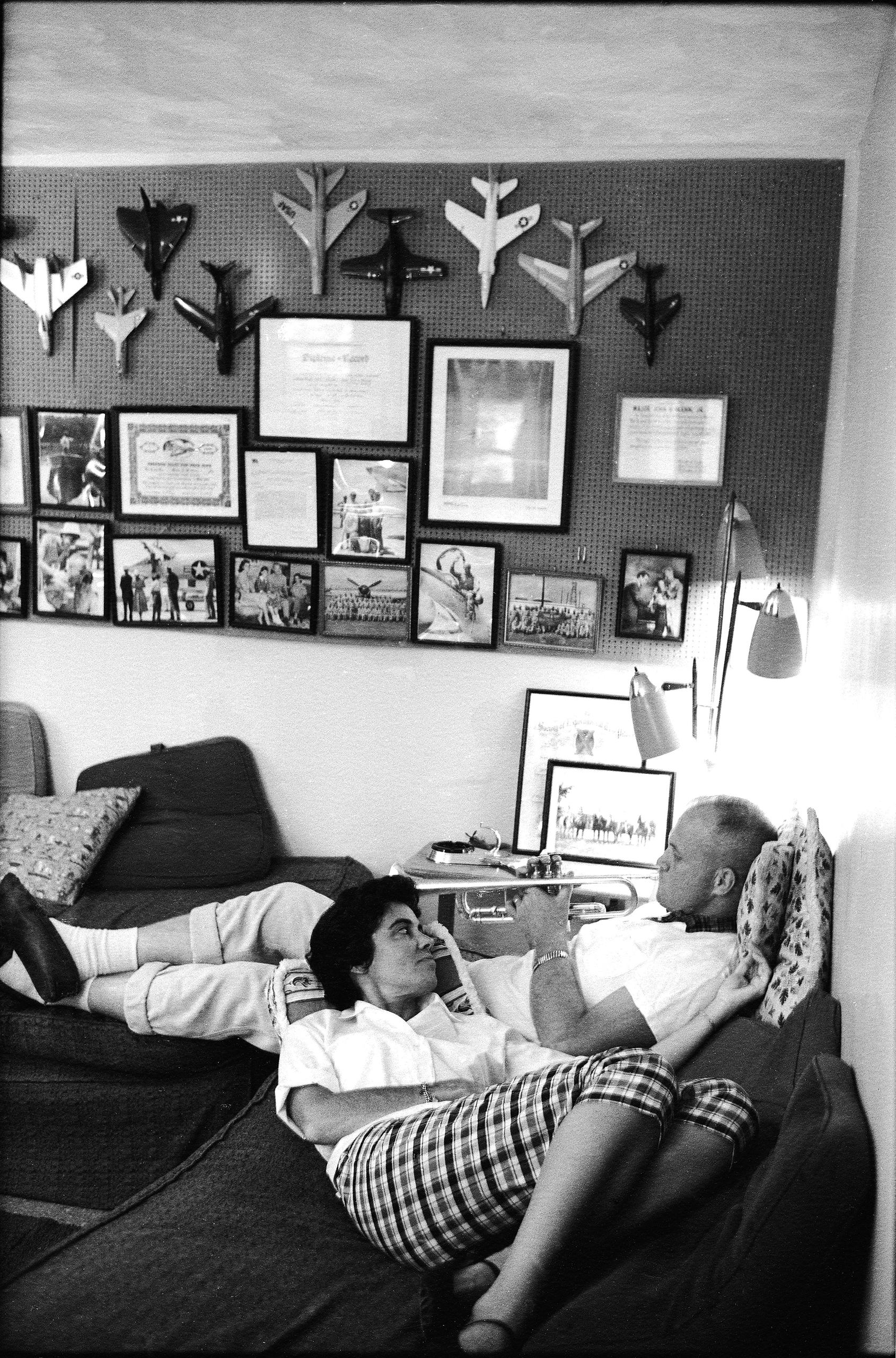

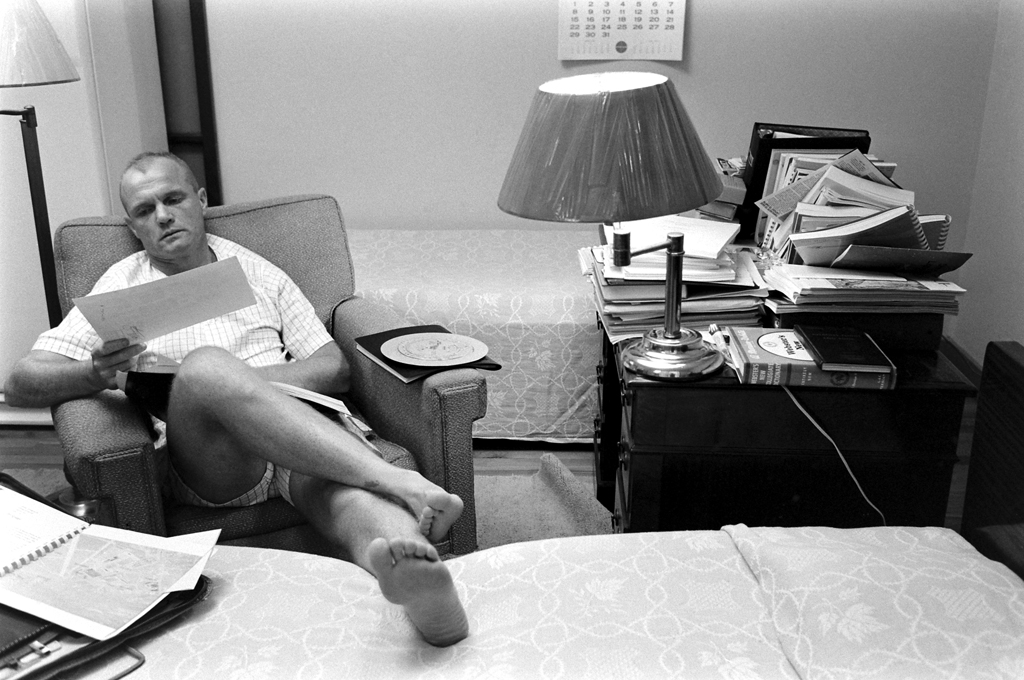

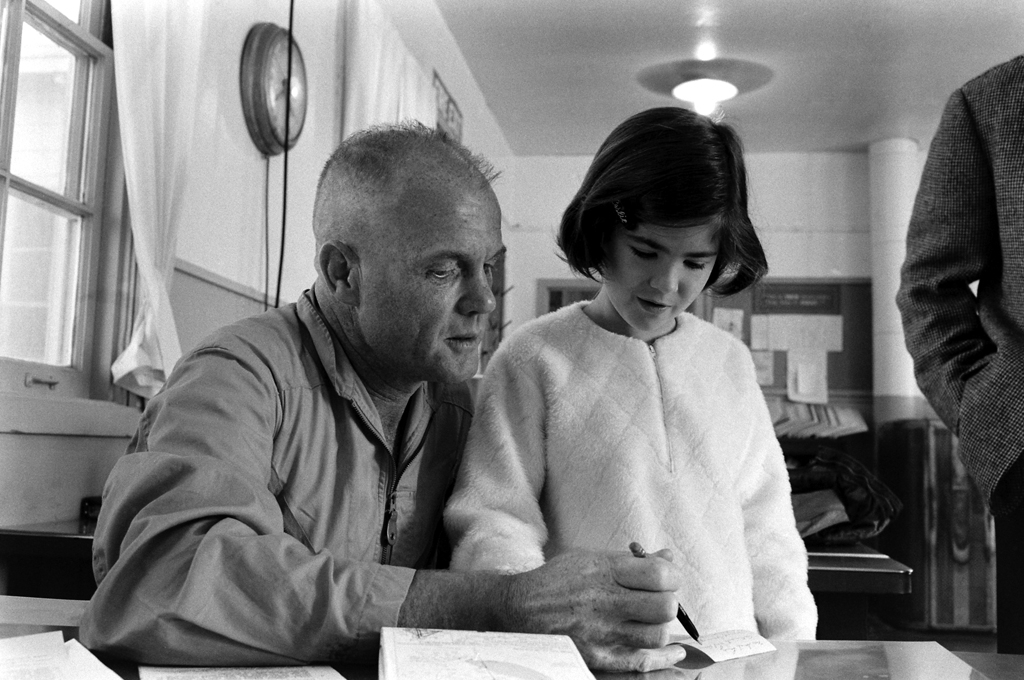

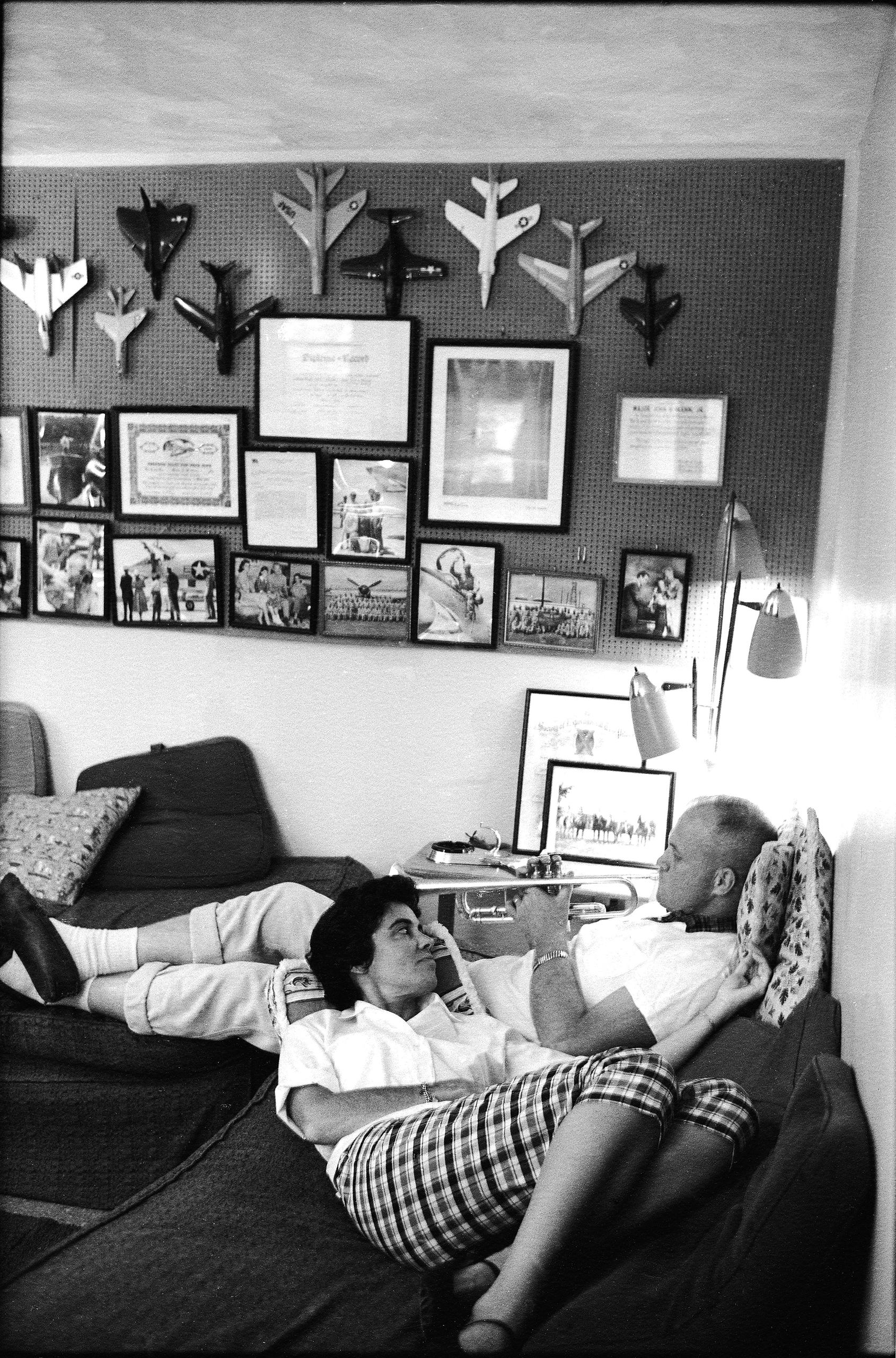

So the staged picnics and happy rough-housing were all set up and shot and then, for Glenn, came the silliest image of all—of the professional fighter pilot and amateur trumpet player, lying on his couch on a lazy afternoon, practicing his playing while his wife Annie relaxes with him. As if a wife could relax while a husband blared a horn in her ear. As if Glenn would even want to put the poor woman through such a thing.

But never mind. Glenn was a military man who never, ever received an assignment from a commanding officer without answering yes, sir and then going on to fulfill that assignment with utter professionalism. And if the commander in his new line of work sometimes was a public affairs officer, well, he’d get the yes, sir treatment too.

Glenn, who died on Thursday at 95, was just one of seven men selected by NASA to both calm and thrill a frightened country—a country that, in the 1950s, was at nuclear dagger-points with the Soviet Union and was, by a lot of measures, losing that contest. The Soviets had the rockets—including the bruising R7 ICBM—that could be used to put a satellite in space (which they did before we did) and put an animal in space (which they did before we did, too) and to put a man in space. And oh boy, did they do that before us, launching Yuri Gagarin in April of 1961—with his Hollywood looks and cover-boy smile—on a full one-orbit lap around the Earth.

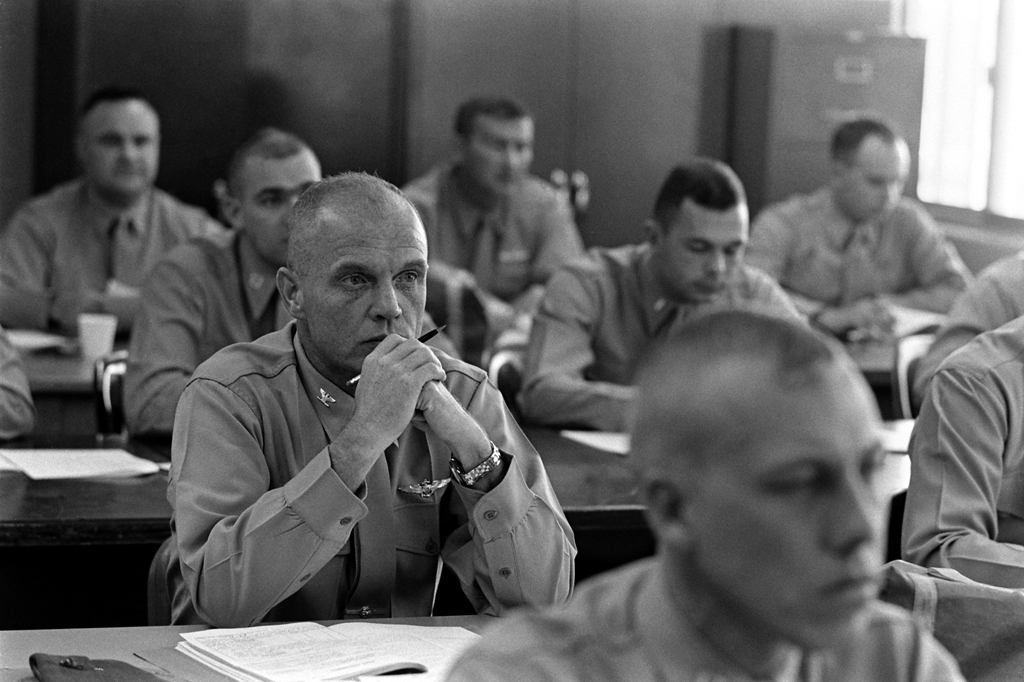

But the the real purpose of R7 and the other ordnance was to rain nuclear hellfire on Chicago and New York and Pittsburgh and Des Moines and if Gagarin’s smile was sincere, it masked something closer to a leer from his country. So the seven Americans with the crisp Yankee names like Deke and Gus and Al and Gordo, with the military crewcuts that telegraphed seriousness and the mischievous smiles that telegraphed fast cars and hard drinking (important parts of the flyboy’s brief) were brought in to buck the nation up.

John Glenn: A Hero's Life in Pictures

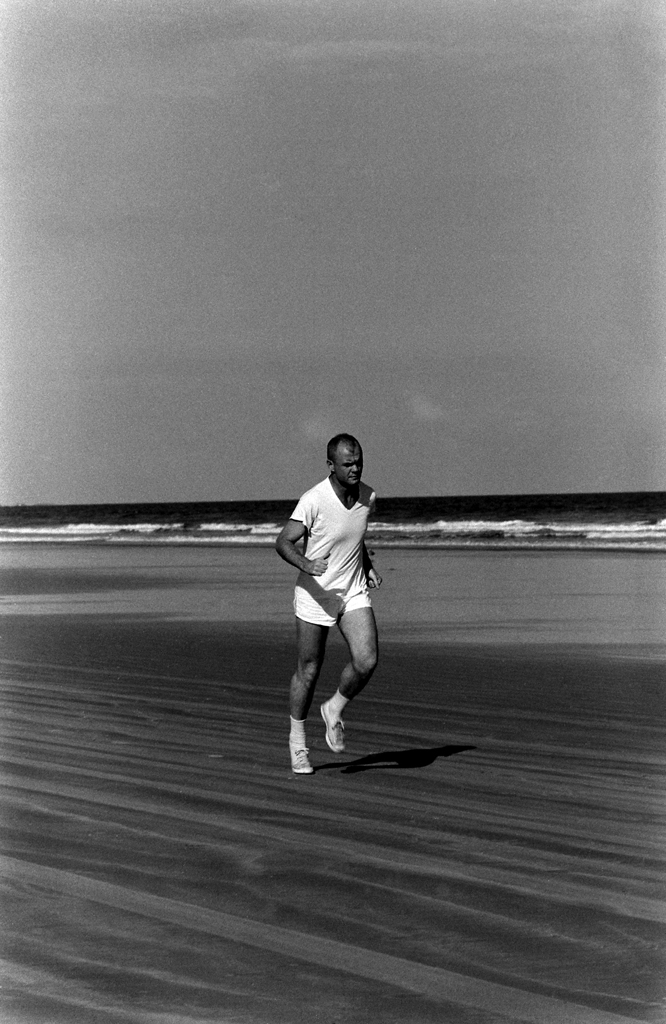

And yet it was Glenn—the least mischievous, indeed the entirely unmischievous—who became the greatest among those ostensible equals. He was the only Marine, the only man who didn’t drink, the one who flew 149 combat missions in Korea and, on one occasion when his Panther fighter took two blasts of anti-aircraft fire that ripped more than 200 holes in its fuselage, radioed to his squadron commander nonchalantly, “I’m going to ease out of here,” before peeling off and bringing his crippled plane to a safe landing.

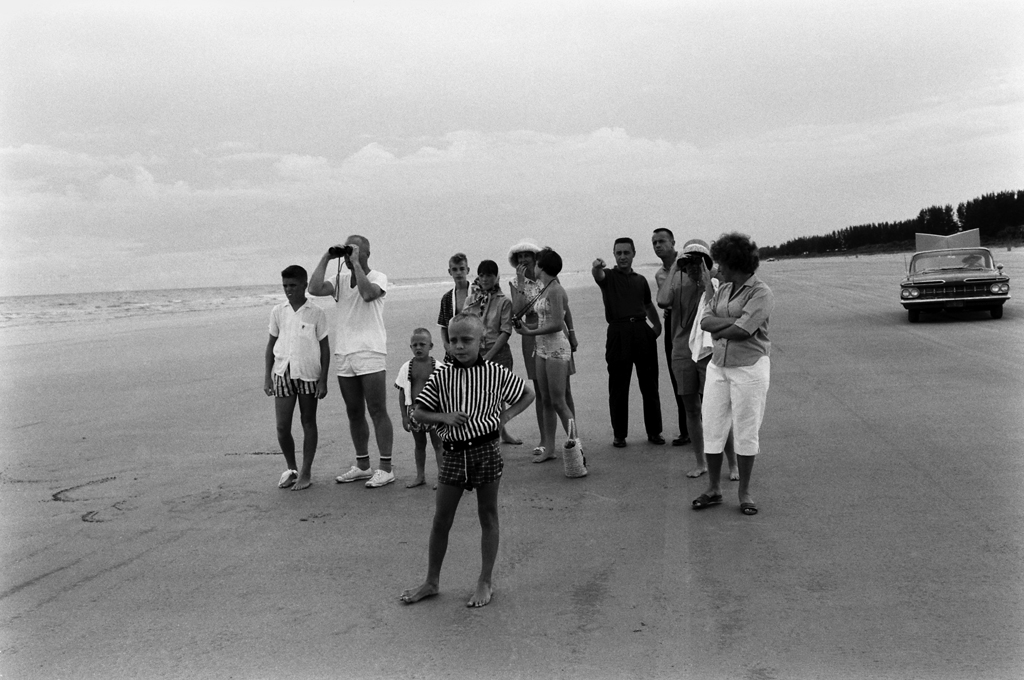

But the crinkle around the eyes was there, and the genuine pleasure in the company of people was there—the kind that had him greeting the same Boy Scout troops all the other astronauts greeted and addressing the same country fairs all of the other astronauts addressed, and yet doing it in a way that suggested that, well sir, there was nothing he’d rather be doing on a beautiful day like this one. The other six, for all their efforts, could never touch that.

It was thus no surprise that while the astronauts who were selected by the NASA brass to fly the first three Mercury missions—Glenn, Gus Grissom and Al Shepard—were chosen entirely on the basis of their skill, the one who was chosen to fly the third of those missions, would need to have something more. The first two flights would be sub-orbitals—popgun lob shots into the lower reaches of space and then straight back down into the Atlantic Ocean just 17 minutes after liftoff. The third flight would be the first orbital flight—and the man who flew that would be the man who, on behalf of his nation, had finally caught the Soviets.

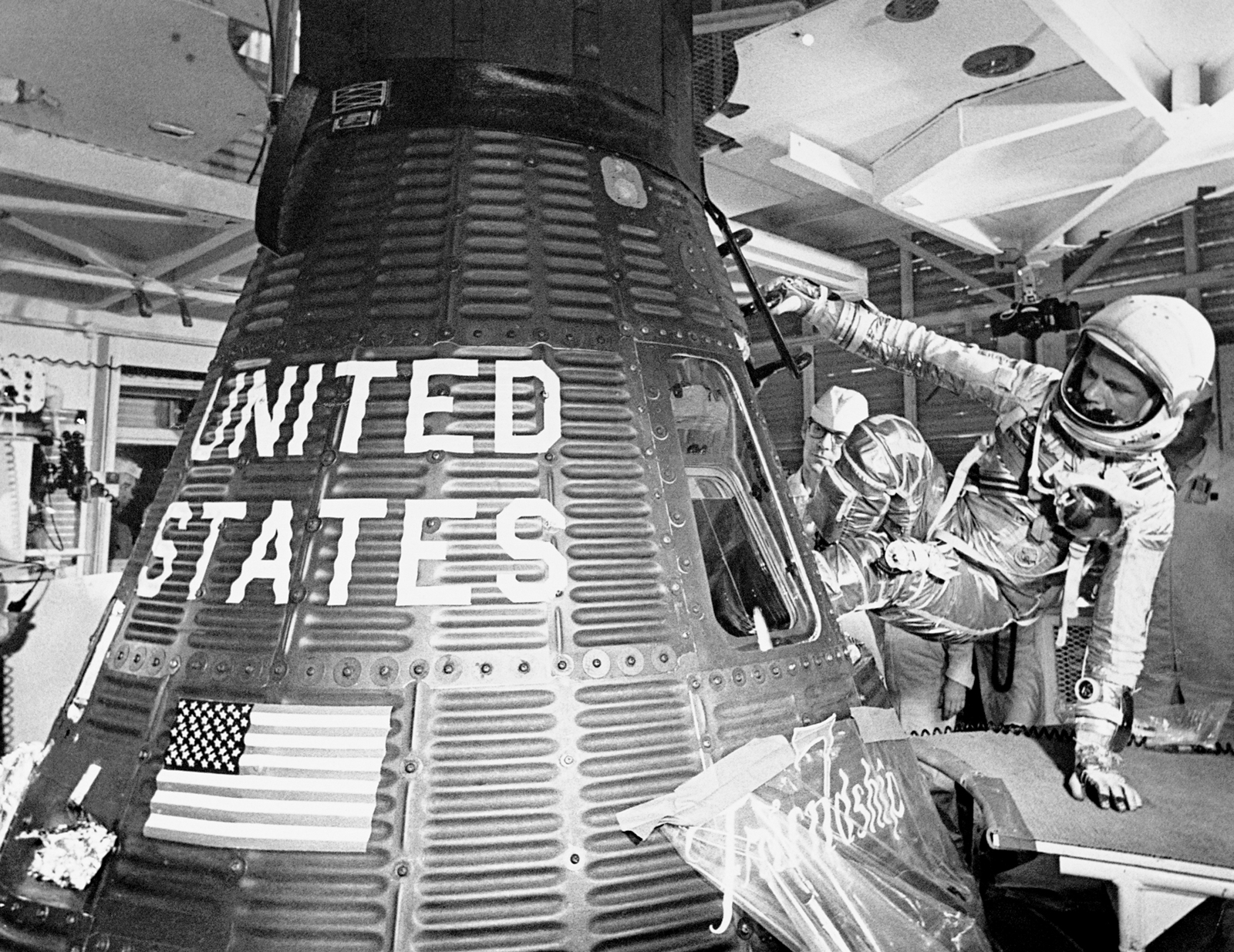

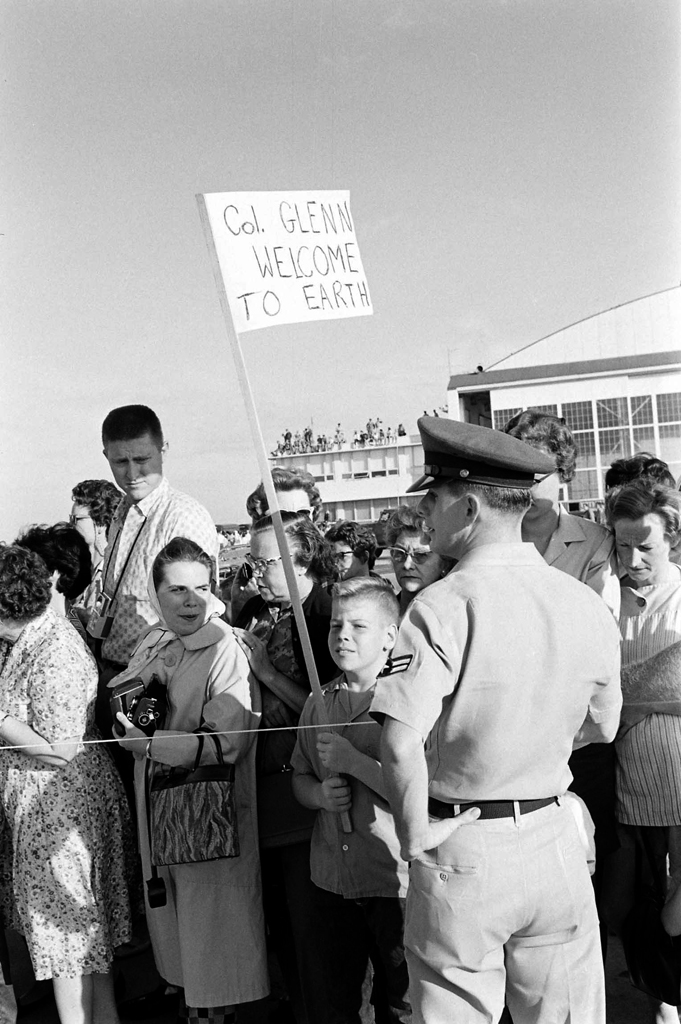

It would be Shepard who would get the first mission and Grissom who would get the second, and becoming the first two Americans in space would be no small thing. But it would be Glenn who got the plum assignment, Glenn who, on February 20, 1962, at the age of 40, circled the Earth three times and came back to a welcome that would make the likes of Lindbergh and Earhart look like mere stunt flyers.

But the mission wasn’t easy and in case anyone doubted the steel behind the Glenn smile, it included a moment not unlike the one he’d faced in his crippled Panther. That moment occurred when a warning light went on indicating that the heat shield on the bottom of his Mercury spacecraft had come loose, meaning the ship and its passenger would incinerate in the 3,000º F inferno of reentry. So Mission Control recommended that Glenn not jettison his retrorockets after he fired them at the beginning of the reentry, because they were strapped into place below the heat shield and might just help hold it in place.

“We are recommending that you leave the retropackage on through the entire reentry,” Scott Carpenter, the Mercury astronaut who was serving as the capsule communicator, radioed up to Glenn. The capcom knew of the problem with the heat shield. The astronaut didn’t.

“What is the reason for this? Do you have any reason?” Glenn asked.

“Not at this time,” came the response. “This is the judgment of Cape Flight.”

And Glenn, who knew enough to know that Cape Flight would never recommend such an irregular procedure, much less conceal the reason for it from the pilot, unless something might be grievously wrong with his spacecraft, responded with two words:

“Ah, roger.”

The call from Carpenter was an order. Questioning it further would not do a single thing to change the circumstances. So Glenn continued with his mission, held onto his retropackage, flew his ship home and the moment his spacecraft with its perfectly serviceable heat shield hissed into the Atlantic, he became an American giant.

For his troubles, John Glenn would be officially grounded by NASA. Like Gagarin, whose Soviet superiors also removed him from the flight rotation, he was considered too valuable an American asset to risk on a second mission.

John Glenn: Rare and Classic Photos From an American Life

“Headquarters doesn’t want you to go back up, at least not yet,” Bob Gilruth, the head of the Mercury program told him flatly, as Glenn recalled for TIME for a 1998 story.

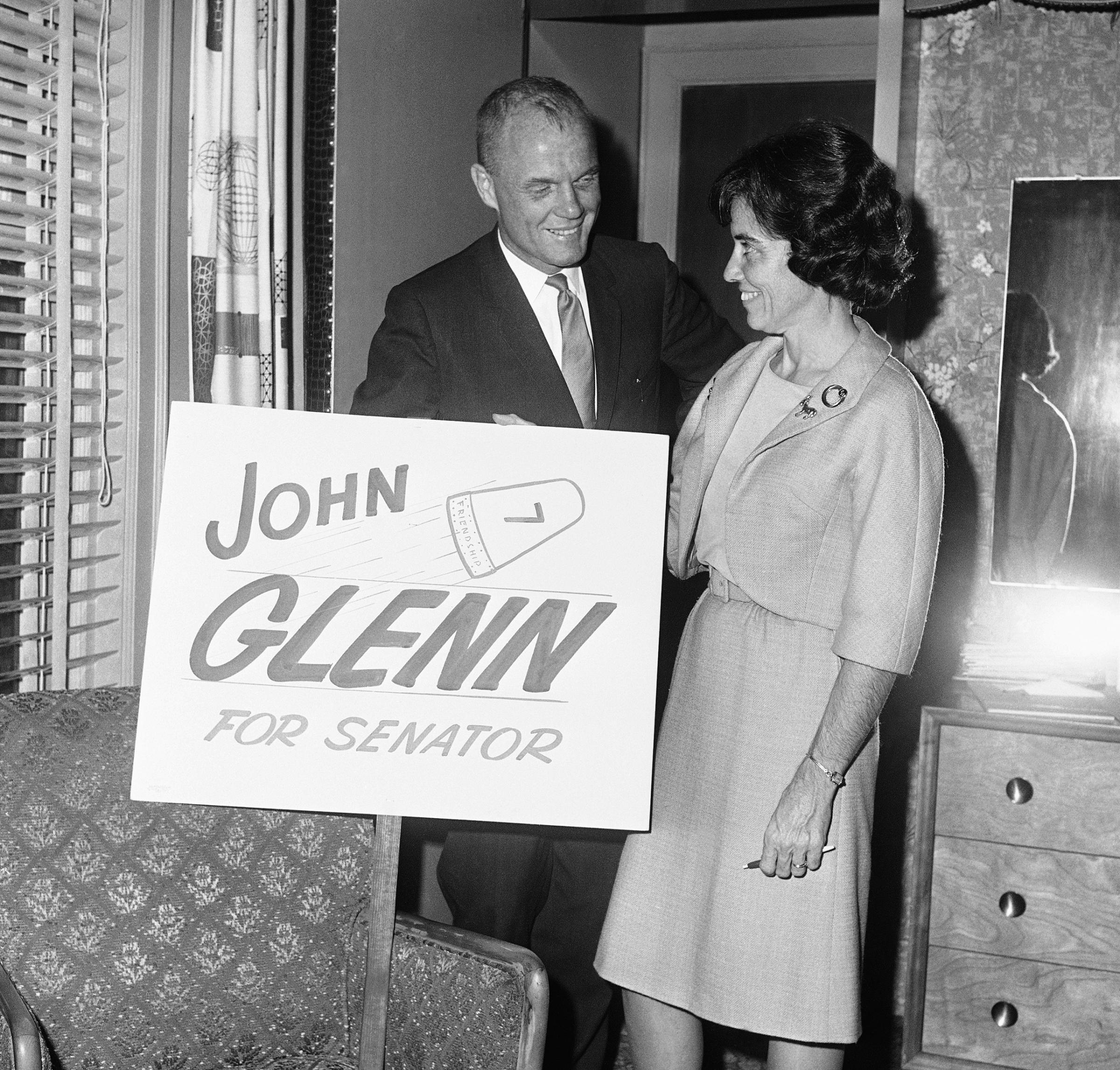

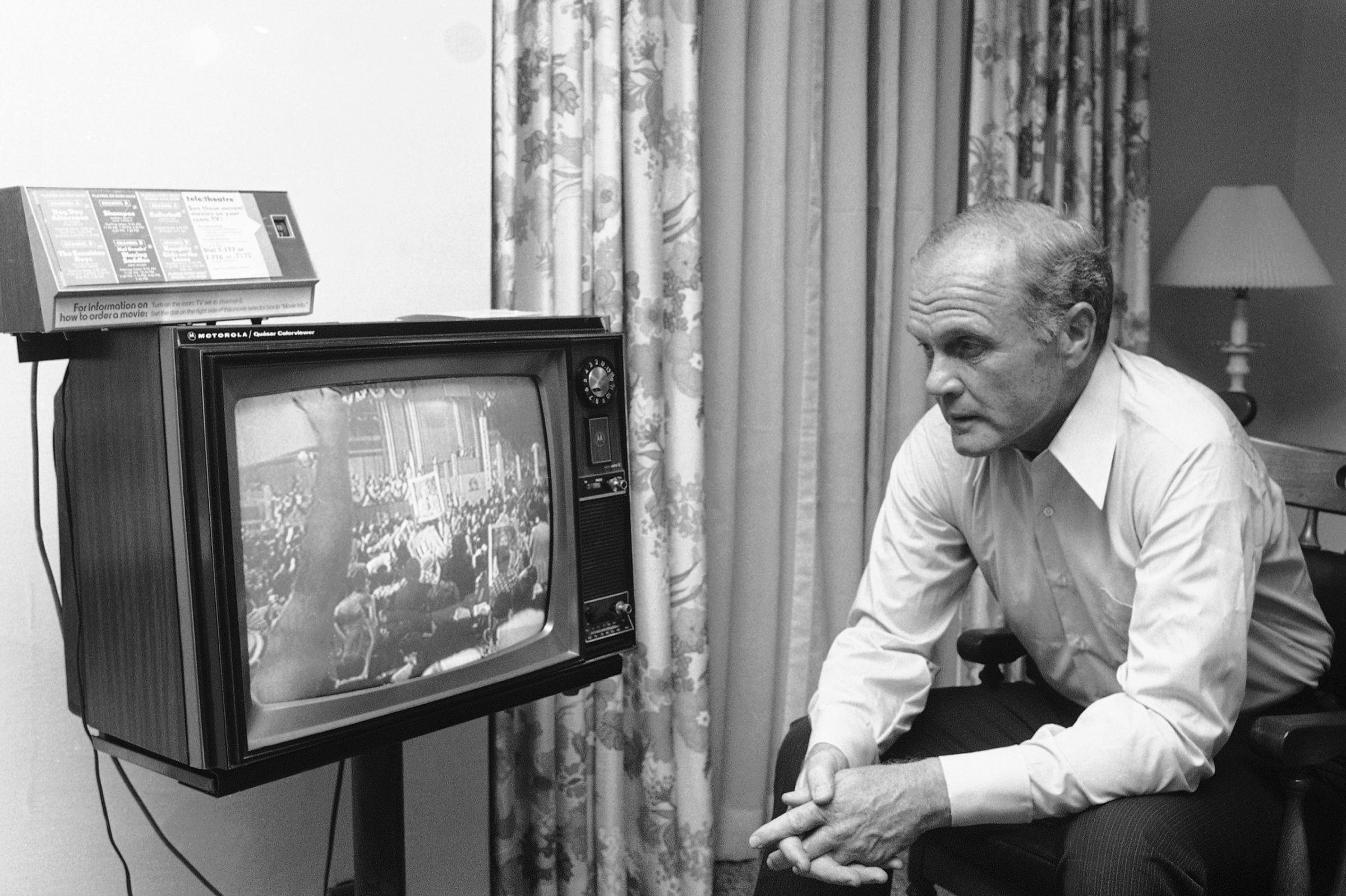

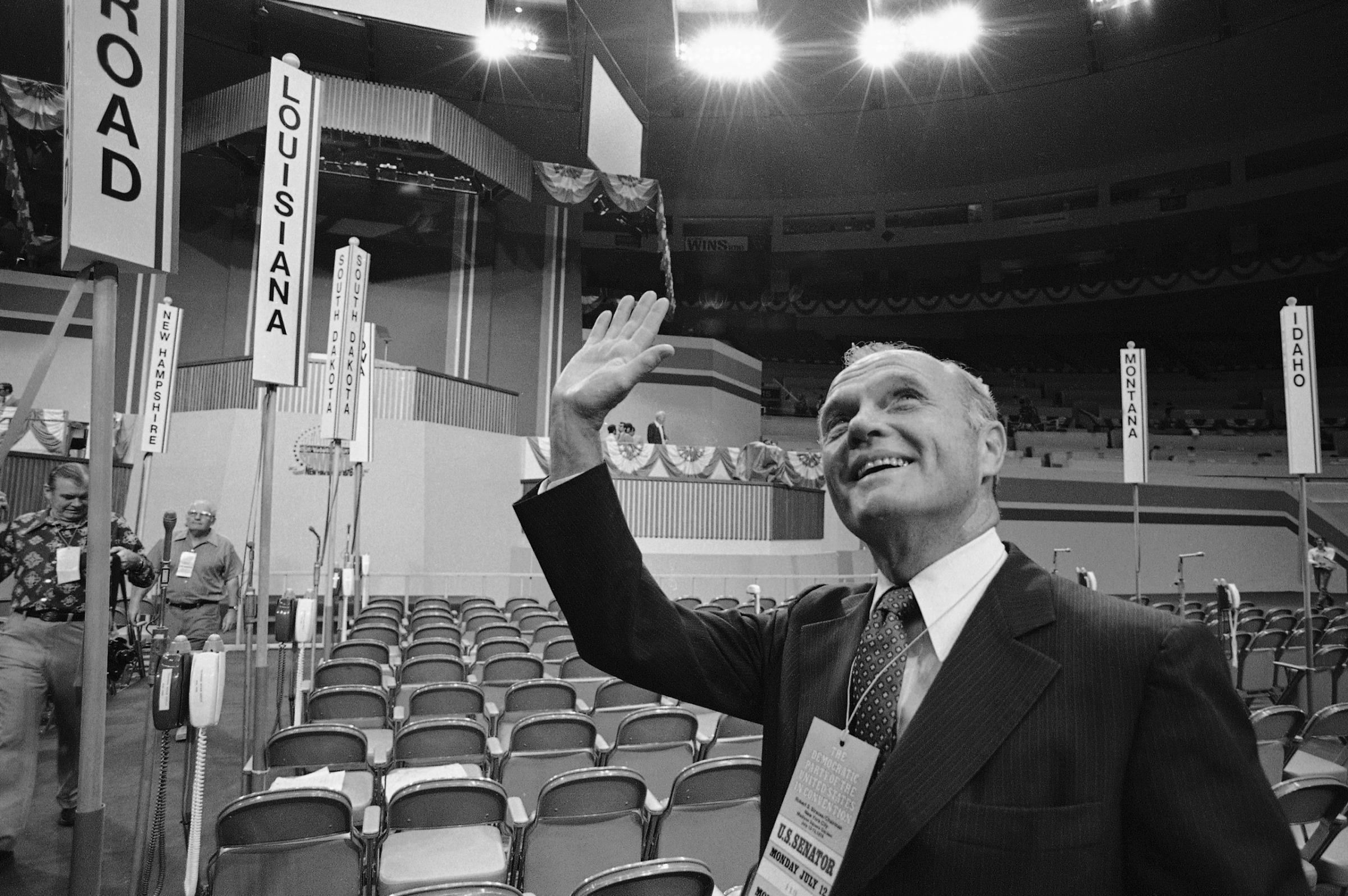

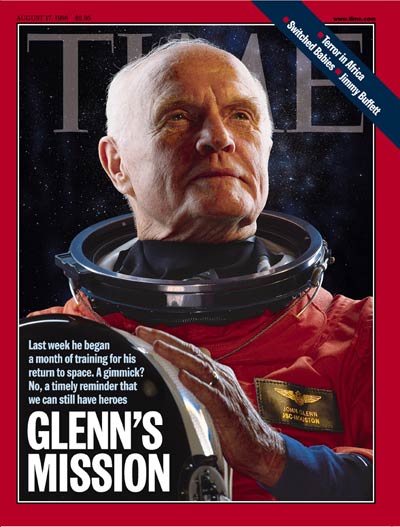

“Not yet” would turn out to be not ever, so Glenn found another way to be of use to his country, running for public office and serving four terms as U.S. Senator from Ohio, from 1974 to 1998. And yet, to his own surprise as much as his nation’s, only a few months before his Senate career ended, he would indeed go to space again, a septuagenarian astronaut tapped by then President Bill Clinton to fly aboard a space shuttle as a payload specialist. Glenn would serve as part crew member and part experimental subject, testing the parallels between the effects of aging and the effects of zero-gravity on the human body, which are surprisingly similar.

If that mission was part national feel-goodism, what of it? So was the entire early space program. And if it was in part merely a way to pay Glenn back for having been denied a return trip to space for so long, well, it was a consolation prize he richly deserved.

Glenn lived his very long post-NASA life with both dignity and humility—not an easy thing for a man who had fought and won in the fiercely competitive world of the astronaut corps. A few months before he flew on that 1998 mission, I visited him in his Senate office to talk about his unexpected return to flight status. Our meeting had to be interrupted so he could meet a group of school children in the atrium of the Dirksen Senate Office Building, and he invited me to come along. When it came time for question and answer, one small boy raised his hand.

“What about those two assistant astronauts you had?” he asked. “Who were they?”

“Assistant astronauts?” Glenn asked. “We really didn’t have assistants.”

“Yes you did,” the boy said. “Those two assistants.”

Glenn, who had no idea what the boy meant, eased himself out of the exchange, answered a few more questions, and we returned to his office.

“It was Shepard and Grissom,” I told him. “He thought they were your assistants.” That was the only thing the boy could have meant—Shepard and Grissom who had gotten the pop gun flights while Glenn got the orbits.

Senator Glenn laughed, but didn’t quite believe it—and the sense I got was that he didn’t want to believe it. For most astronauts, that would have have been the very first guess. For the humble Glenn, it was the last.

But it was something else, something Glenn said about his wife, Annie, that stayed with me the most from that day. Annie spoke with a terrible stutter and yet learned to battle through it because an astronaut’s wife could not be an astronaut’s wife if she couldn’t talk to the press. In the process, Annie also learned to live with the trumpet blasts that came with being married to someone who was at one time the most famous and beloved man in America.

John and Annie were neighbors when they were born, and they played together as babies. “I like to say we met in the play pen,” he told me that day. And then he added, more reflectively: “I’ve never known a world that didn’t include her.”

So many Americans have never known a world that didn’t include him. And now all of us—Annie most acutely, but the rest of America too—will have to adjust to a world that is different. And is poorer.

“Godspeed, John Glenn,” Scott Carpenter said through the Cape Canaveral microphone when the engines of Glenn’s rocket lit that day in 1962. Godspeed, Americans say again in 2016.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com