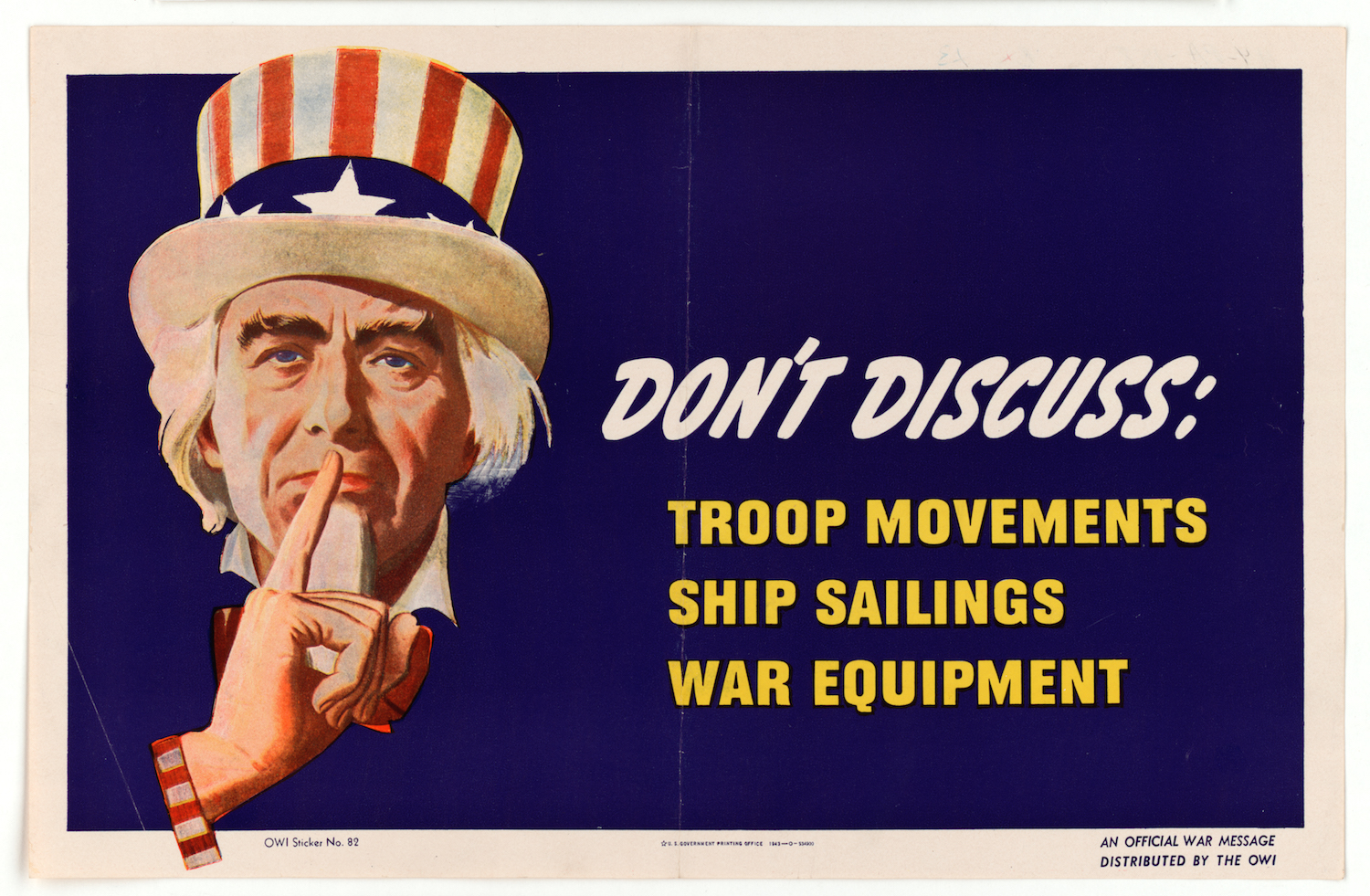

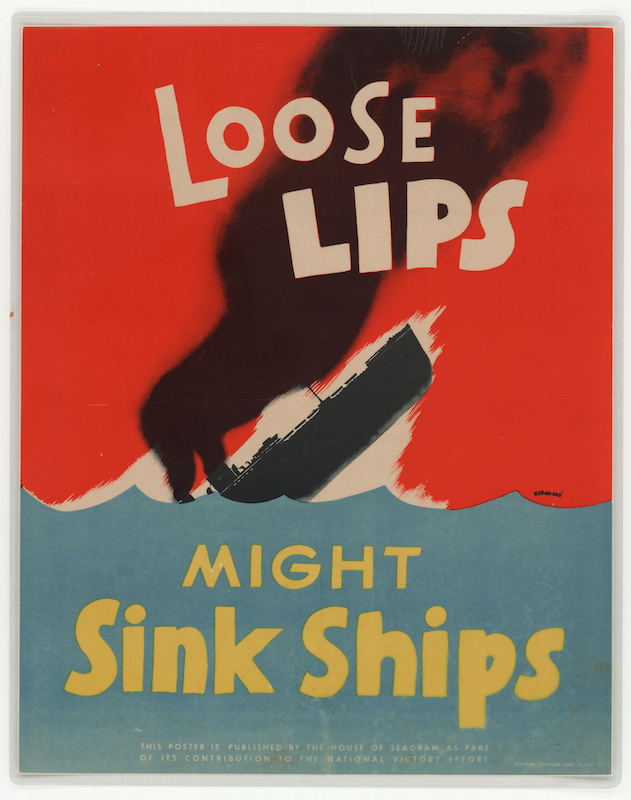

The expression “loose lips sink ships,” has become part of the American popular lexicon, almost as common as other expressions such as “going cold Turkey,” or “pitching in.” Despite its humorous nature, a very serious and profound history exists behind the statement. During World War II, the U.S. military establishment commissioned numerous artists in cooperation with the The Office of War Information (OWI) Bureau of Graphics to create and distribute propaganda posters.

These posters were widespread and mass produced, aimed at improving domestic morale and encouraging enlistment, citizen involvement, conservation and other efforts to help the war effort abroad and at home. As Alan Winkler explained in The Politics of Propaganda, the U.S. government was initially reluctant to engage in a mass propaganda campaign. The U.S. government was afraid of the power a centralized information bureau could wield, having witnessed it with Joseph Goebbels’ campaign in Nazi Germany, and Congress was wary of allowing the OWI to operate separately from diplomatic and military oversight. Pressure from private interests, however, led to the creation of “information campaigns,” through numerous outlets, including print.

Independent poster producers, sometimes from the private sector, forced the government’s hand in creating a central bureau to oversee what exactly was being disseminated, and which information was crucial to convey to the wider public. A similar campaign was created in Great Britain, as well as Canada and other states sympathetic to the Allied war cause. The dissemination of the physical posters was coordinated through organized groups that volunteers would plaster on a variety of public spaces, including churches and schools.

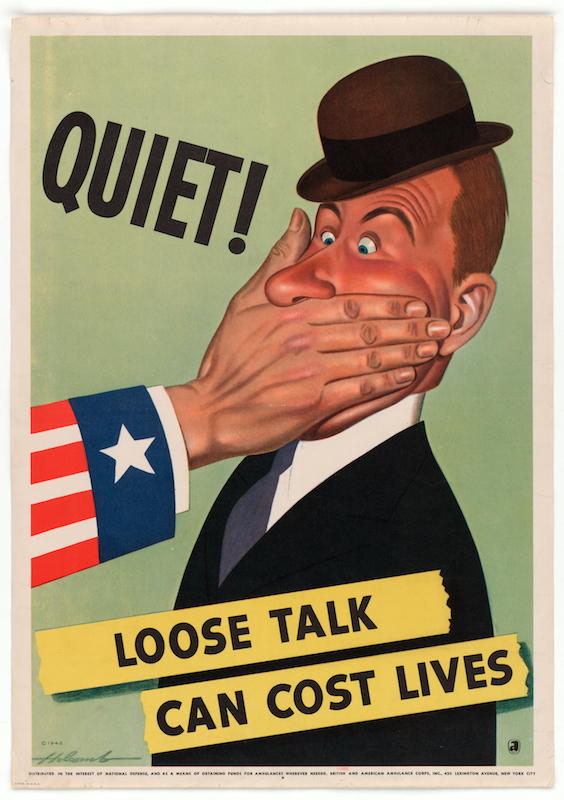

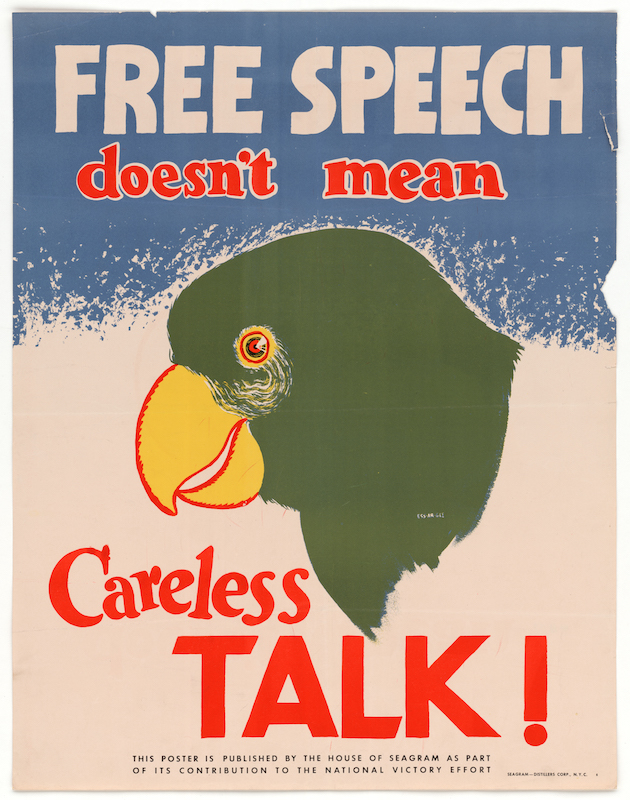

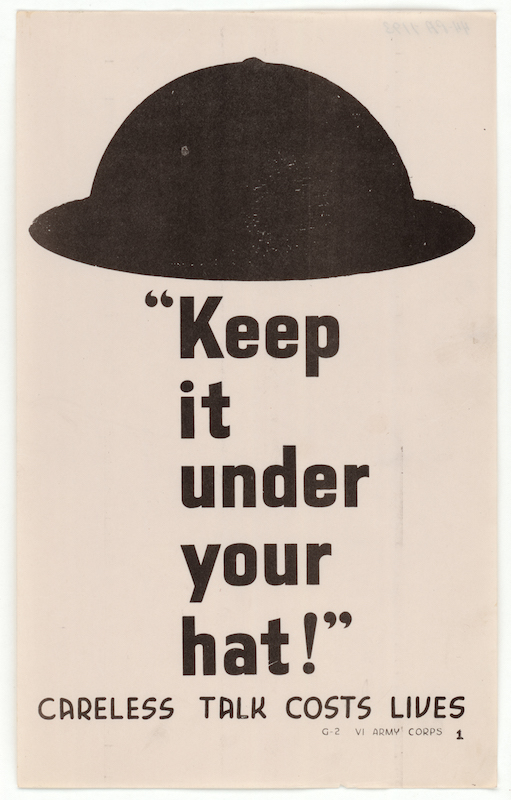

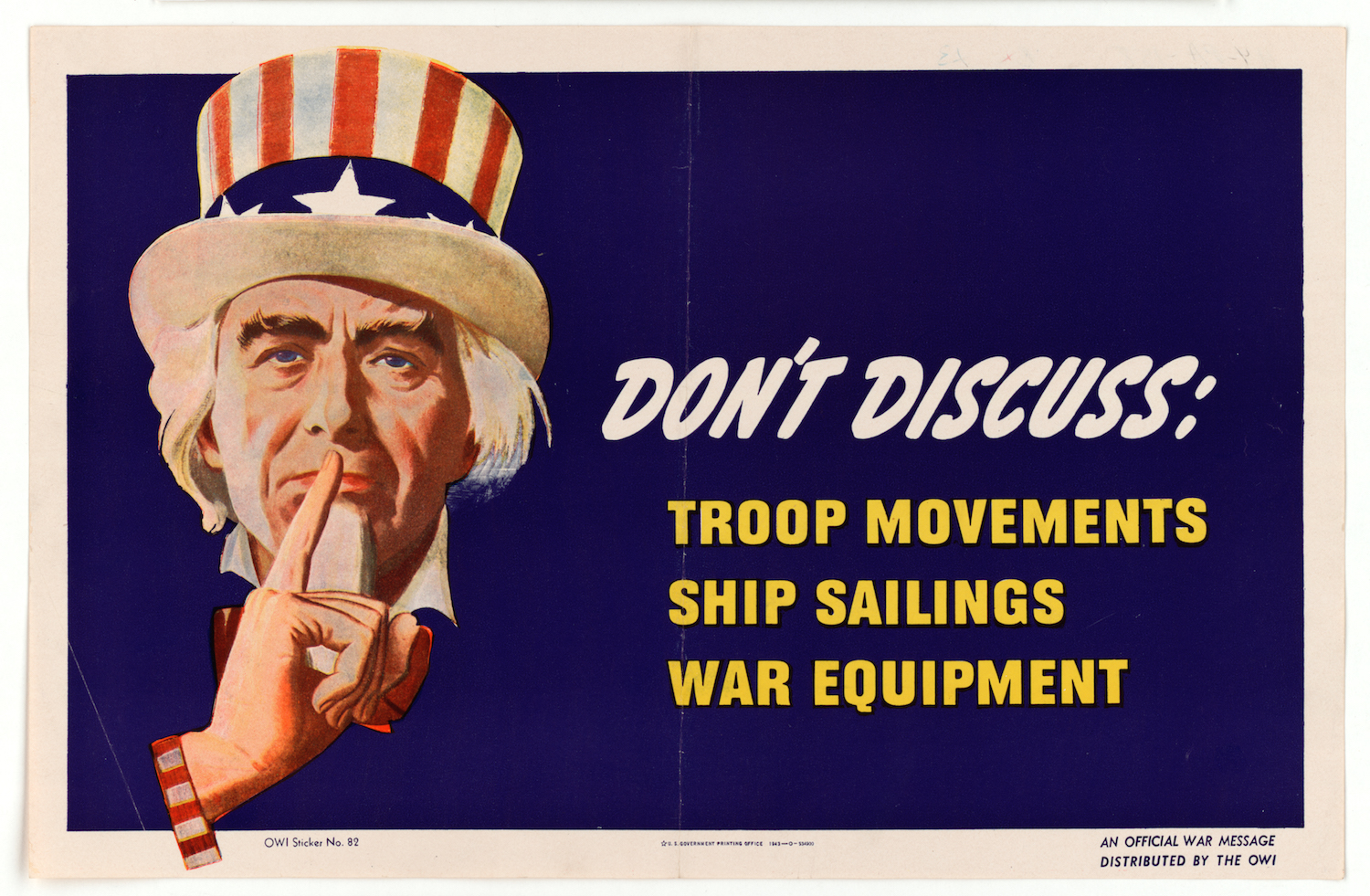

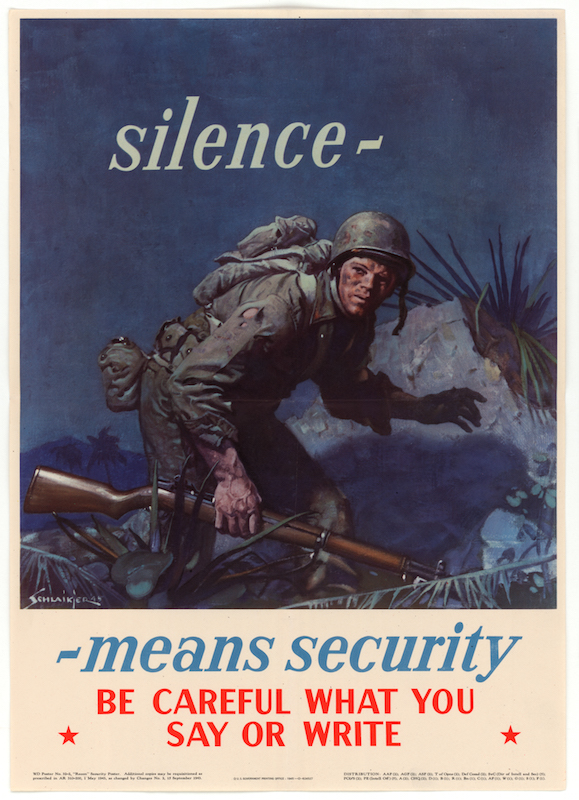

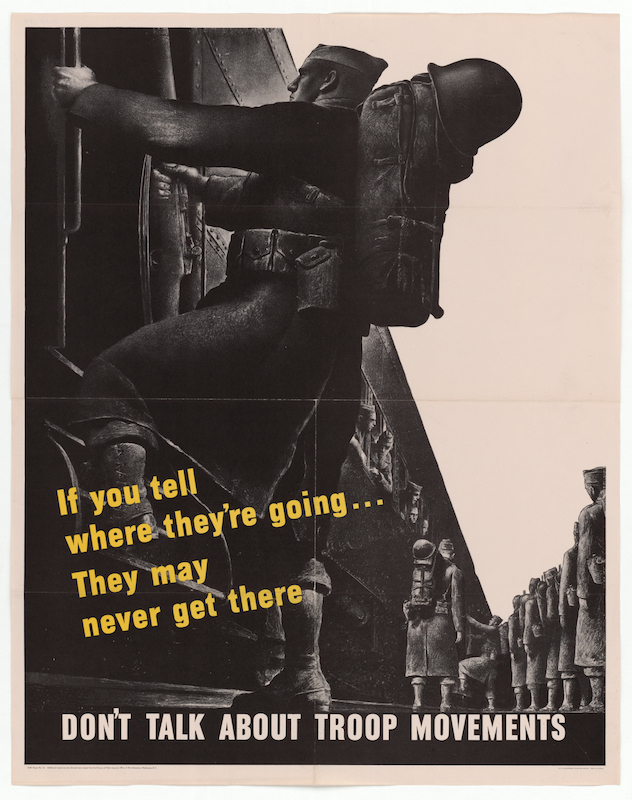

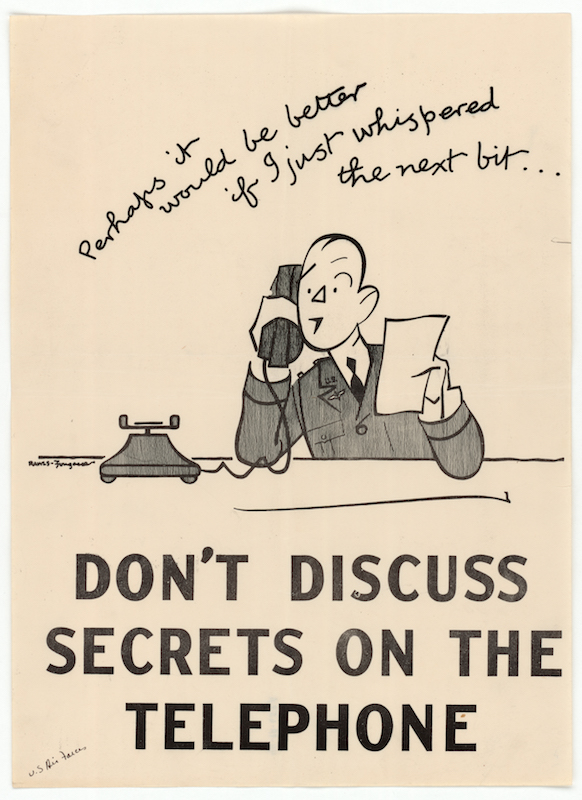

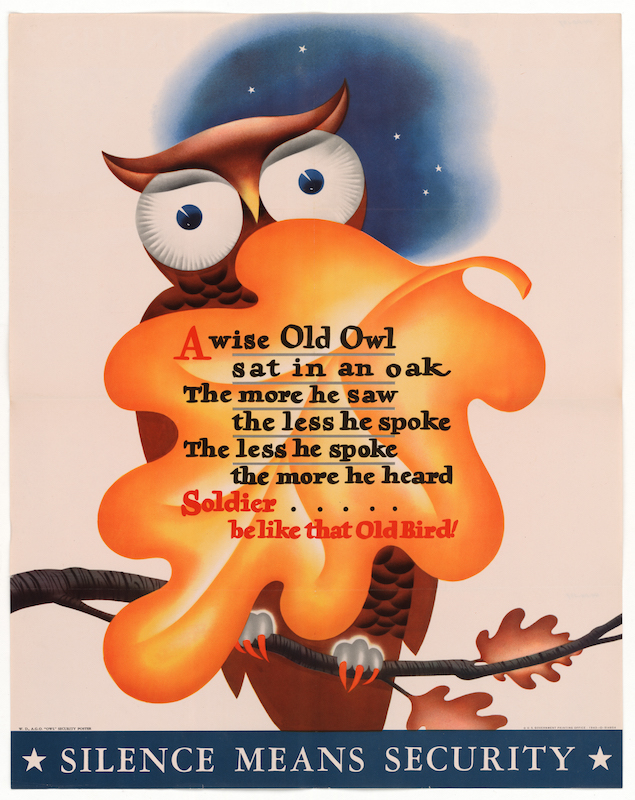

Even though the propaganda campaign in the U.S. tended to have a positivist theme, portraying smiling faces, Allied victories and patriotic zeal, many depictions of the enemy were outright racist in nature, and depicted the enemy in extremely negative and stereotypical fashion. One of the most important functions of these propaganda posters was the attempt to cut down on “careless talk.” The United States was afraid of critical information being intercepted by the Axis, which could lead to mass casualties if the enemy acquired prior knowledge of ship lanes and troop movements.

The OWI campaign commissioned unpaid artists to submit their work, using various symbolisms to get the message across. One of the most popular types of “silence” posters featured the image of grieving family members, or even pets, mourning the loss of those who had been killed as a result of reckless speech. Guilt was undoubtedly the biggest emotion artists were trying to stir in viewers. Other posters depicted the Nazis “awarding” medals or acknowledgements to American citizens who had “contributed information” leading to their victories.

But, while the possibility of causing a death was made explicit by these posters, they also served another function: preventing people from spreading rumors that might sap morale.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

But were the posters simple paranoia on the part of the U.S. government, or a truly necessary campaign that rooted out saboteurs, spies and enemy agents? There were two serious attempts to sabotage and spy on American war aims by the Nazi regime, notably Operation Pastorius and Operation Elster.

Even though both were ultimately unsuccessful, they still proved the American government correct in its cautious mentality and the need to have a populace that would not spread known critical information. In addition, the Duquesne Spy Ring, the largest espionage case in United States history to end in convictions, proved that serious attempts at information gathering and sabotage were deeply rooted, and existed well within the American homeland.

Propaganda posters proved to be a cheap and accessible form of mass public information. The campaign utilized the emerging psychology of advertising with the powerful motifs of patriotism and loyalty to discipline the citizen base – and the posters remain an important indication of the extent to which the entire population was mobilized for war.

Albinko Hasic is a PhD candidate at Syracuse University, whose research concerns U.S. military propaganda.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com