In the late 19th century, an elite group of American women—thanks to women’s colleges like Vassar and Wellesley—were able to pursue levels of higher education that had been denied to their forebears. Yet after graduation, they often found that even those degrees were a dead end: they still did not have the same career opportunities as their male peers.

Well, mostly. In one professional corner, at least, they thrived.

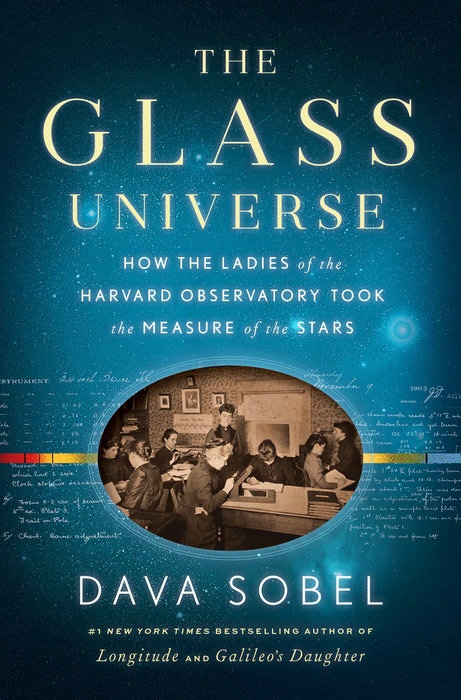

At the Harvard Observatory, women actually made up the majority of “human computers” who analyzed glass plates depicting photos of the stars. These women—and the heiresses who funded their work—are the subject of a new book by Dava Sobel, The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. “They were good at math, or devoted stargazers, or both,” Sobel writes in the book’s preface. “Some were alumnae of the newly founded women’s colleges, though others brought only a high school education and their own native ability. Even before they had the right to vote, several of them made contributions of such significance that their names gained honored places in the history of astronomy.”

From 1885 to 1992, men at the observatory made half a million glass plates depicting the stars, which the women would analyze each morning.

“They worked six days a week, minimum seven hours a day, and they would find plates waiting for them when they came to work,” Sobel tells TIME. “Depending on the project they’d been assigned, they would be looking either at chart plates, which show the positions of stars, planets, asteroids, anything in the sky, or spectra plates, where the starlight had been passed through a prism. Instead of seeing what look like stars, there would be little shaded strips, and from the patterns of lines and shading in those strips, the women would be able to make a determination of what type of star it was.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the beginning, Sobel says, the field was one of mysteries. “No one know what the stars were made of, why they were different brightnesses, how far away they were, everything was at the starting point—it was really the dawn of modern astrophysics.” But over time, the analysis done by the women at Harvard led to major breakthroughs in the field, including a classification system for stars that’s still used today, known as the Henry Draper Catalogue. “The other big thing was the discovery that led to a means for determining distance in space,” says Sobel. “That was Henrietta Leavitt. And that is still so important that current astronomers want the name of her discovery, which is called the Period-Luminosity Relation, [to be] changed to the Leavitt Law.”

Surprisingly, these remarkable women met little resistance to their authority in the field. “From the beginning of their work, it was clear they were doing something important, and it wasn’t happening elsewhere,” Sobel says. “As early as 1893, Williamina Fleming was invited to address a meeting of professional astronomers. I think that’s one of the most appealing parts of their story, is how well accepted and recognized they were in their own lifetime.”

The influence of these women continues today as the half-million plates they analyzed are going digital. “Nobody makes glass plates anymore,” Sobel says, “but that makes the collection even more valuable, because it preserves the sky as it looked then. For current discoveries, the plates provide a way to look back at that sector of the sky and see if there’s any trace of the object there at that time.”

For women thriving in the workplace at a time when their peers stayed home, that’s a pretty bright legacy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com