I was hoping for a great Olympic meet. We’d set things up so I’d have a good shot to build on the success that found me in London in 2012. That’s why I came home from school, spent a year training with my longtime coach Todd Schmitz and my trainer Loren Landow, put the rest of my life on pause so I could devote my full attention to these games and work myself into the best shape of my life. But as you now know, Rio didn’t exactly go as planned. (How’s that for the understatement of the year?) Oh, I fought my way onto the team, qualified in three events, but if I’m being completely honest, this just wasn’t my Olympic year. Not even close, it would seem.

I could tell at trials. Everyone could tell, looking back, but when I was down there in that pool, struggling to find my rhythm, my mojo, I could tell most of all. I was having panic attacks for the first time in my life. Loren, my trainer, would sit with me and talk me through these uncertainties, and help me to meditate. I don’t think I would have gotten through that week in Omaha without his help. Without those meditations, my throat would close, I couldn’t breathe, and I’d start to shake uncontrollably. I couldn’t explain it, couldn’t understand it … but there it was. And all I could think was, What is happening? This isn’t me. This isn’t me.

I hated that the sport I’d loved so much, had given me so much, was making me feel the way I was feeling during trials. So unsure of myself. So off my game. So unlike … me.

I guess you could say I was done before the finals even started—and before I could even get my head around the idea of not qualifying in an event I’d won four years earlier, I had to worry about swimming the 200-meter freestyle.

I wish I could remember where my mind went during those low, low moments, but I do know this: there’s not a thing I would have done differently. Not a thing I could have done differently. All I could do, really, was fight through whatever doubts I was facing and keep swimming. And that doesn’t just mean how I handled the unfamiliar pressures during trials—and, later on, during the Olympics. No, I’m also referring to the buildup to the games. I did everything I possibly could. I worked harder than I’d ever worked before.

It was a yearlong grind.

To put in all that work to make it to these Olympics, to qualify by the grace of God in three events, and to fall short of the finals in all three. But the hardest thing I had to do in Rio was climb into my seat in the athlete stands for the finals of the 200 back, an event I’d won in London, with a world-record time. An event that was going on without me.

I could either kick myself and wallow in self-pity, or I could find a way to grow from this Olympic experience and to stand as a different kind of role model in defeat. It’s one thing to inspire all these little girls by winning a bunch of medals. That’s easy. But it’s another thing entirely to be an inspiration when things aren’t exactly going your way. I thought about this a lot, as the Rio games approached. I thought about how I’d been moving about the planet with all these great expectations—expectations I’d placed on myself, mostly, but ones that were also shared by the media, by my sponsors, by my fans.

I realized that if I wasn’t able to be the athlete I was projected to be, all I had left was to be the person I was projected to be, so I wiped away those tears and vowed to do just that. I would stand in support of my teammates. I would be gracious in defeat. I would answer every question thrown at me by reporters. I would make time for my fans, my sponsors. I would still be that person on those billboards, still be the face of these games, only I’d be coming at it from a different place.

Everyone knows what it’s like to fail—and here I’d failed in front of billions of people. I’d let my teammates down. I’d let my country down. I’d let myself down, most of all. And yet through it all, I kept reminding myself that everyone knows what it’s like to work hard for something and not get it. The real opportunity here was in showing the world what failure can look like, in a positive way.

One of the first things I did after my disappointing showing at trials was to make an appointment to heal. I started thinking about what it means for me to feel at home, to be at peace with myself.

I’m determined to rediscover the joy of swimming that helped me to win all those medals in London, putting up times that still stand as world records, Olympic records. I don’t feel that joy right now, but I know it’s in me. Deep down. Somewhere. I need only to tap back into it, embrace it, make it once again my own.

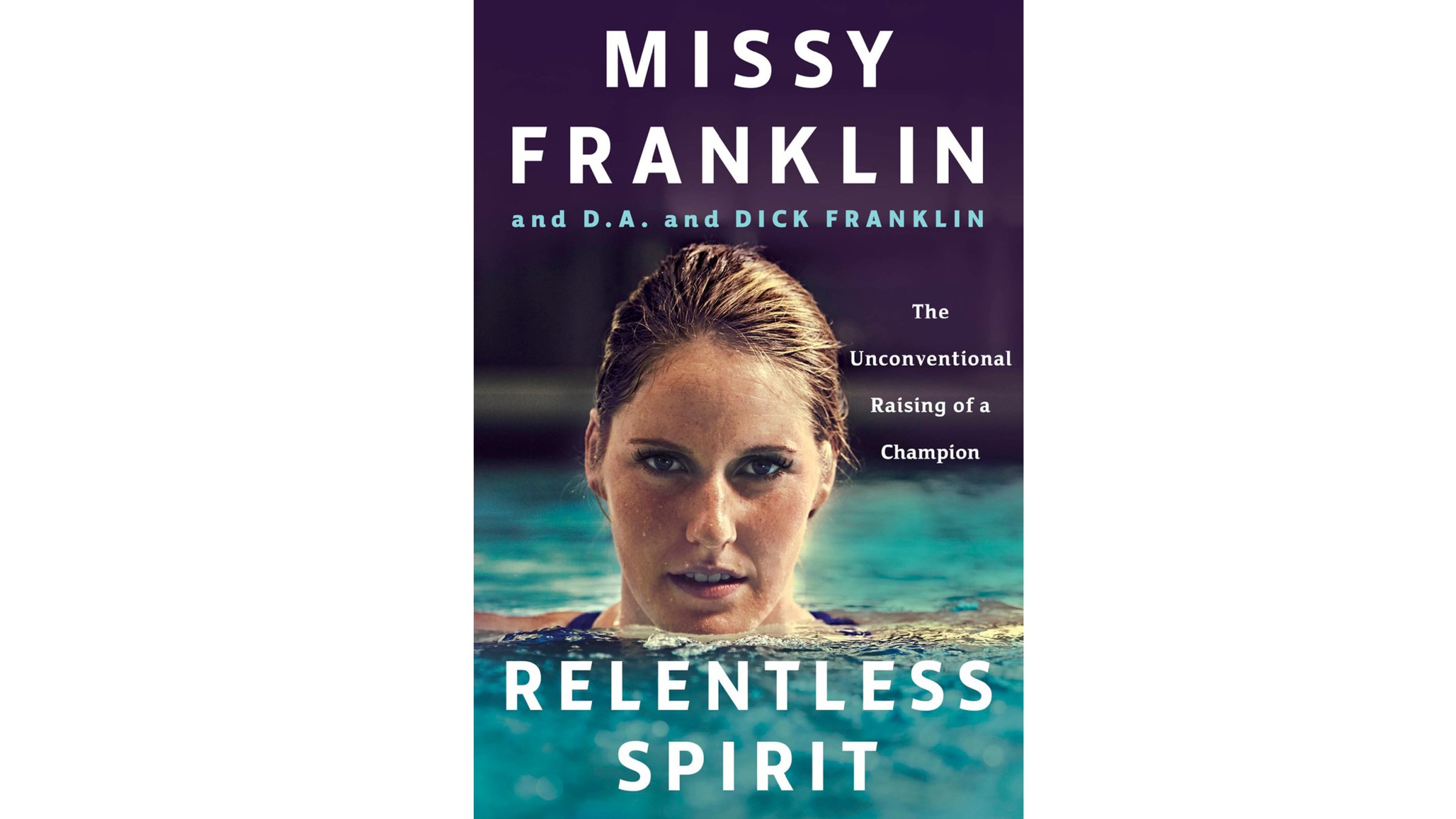

Missy Franklin is a five-time Olympic gold medalist and author of Relentless Spirit: The Unconventional Raising of a Champion.

Excerpted from Relentless Spirit: The Unconventional Raising of a Champion by arrangement with Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © 2016, Missy Franklin.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com