In January 1979, America was in a bad state. The excitement of down-home Georgia governor Jimmy Carter’s election as president three years earlier—and the hope that it would move America past the fissures opened by Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal, the end of the wretched Vietnam War, the fall of Saigon in 1975, and the busing crisis of the ’70s—had disappeared. Islamic revolutionaries’ overthrow of the Shah in Iran had caused an oil crisis, driving gas shortages and spiking prices in the U.S. that would soon result in another round of mile-long gas lines. In the aftermath of this turmoil, creeping unemployment and inflation would both reach double digits.

The coming months would also bring the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the American boycott of the Summer Olympics in Moscow, and the 444-day captivity of fifty-two hostages from the American embassy in Tehran by the followers of Iran’s new leader, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. That summer of 1979, Carter would deliver a speech to the nation in a cardigan sweater about the malaise he saw at the heart of America’s national soul, which only made him look weaker and more pathetic. It would pave the way to the White House for the sunny former actor and tough-talking Republican governor of California, Ronald Reagan, who called America “a shining city on a hill,” promised to bring the hostages home from Iran, and urged Americans to believe in themselves and their country again.

Before all that happened, though, on one snowy Saturday night in late January 1979, four friends and I decided over dinner to start a new national political party.

We began to assemble, more by instinct than by design, the basic building blocks of a party. We needed a candidate for president—someone whose stature would give our new party instant credibility, who shared our convictions, and who could make our case to the American people.

We had only two men in mind: Barry Commoner and Ralph Nader.

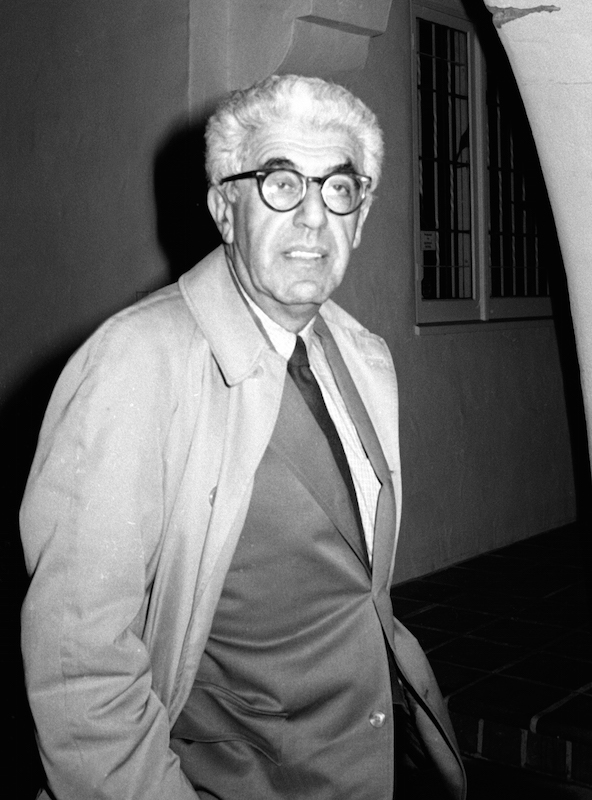

Commoner had the public stature we needed in our candidate. He was a household name, widely respected, and very popular. TIME had splashed him across its cover in 1970, calling him “the uncommon spokesman for the common man.” A Harvard PhD in biology and a professor of environmental science at Washington University in St. Louis, he spoke with the authority of a scientist. Barry declined and offered instead to help recruit Ralph Nader. This was no false modesty. He genuinely believed Nader would be our strongest choice.

A few weeks after Commoner turned us down, we took Ralph to dinner at a Thai restaurant near the White House and tried to persuade him to be our candidate. Even after all these years I can still hear Ralph’s voice careening down Pennsylvania Avenue into that spring evening, full of what he thought was self-knowledge and certitude, as he declared, “ I will never run for president!” He would, of course, go on to run for president five times over the next thirty years, most disastrously in 2000, when his quixotic campaign took just enough votes away from Democratic vice president Al Gore to hand the presidency to Republican governor George W. Bush of Texas. Ralph and I were friends, but I haven’t spoken to him since then. Sometimes, I don’t even wear a seat belt.

Hearing that Nader had turned us down, Commoner jumped in as a full partner and our natural leader as if he had been with us from the first. We had no illusions that we could win the election in 1980. Our goal was to get at least 5 percent of the vote, which would qualify us for several millions of dollars in federal funds for the 1984 election. We would use it to build an enduring party: the Citizens Party.

But we faced two suffocating realities in 1980 that doomed our hopes of Commoner winning 5 percent of the vote: the independent candidacy of John Anderson and the power of the media to frame the race. I understood the first, but the second still makes my head spin.

Barry Commoner’s candidacy hardly existed, because TV didn’t consider him a “story.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Commoner wanted to avoid the traditional campaign’s emphasis on images and symbols. He wanted to focus on substantive issues. He wanted to offer the voters intelligent choices about critical policies and to debate them with other candidates. He had been campaigning for months, but it wasn’t working, and he was increasingly irritated with his lack of media coverage. In particular, it plagued him that the stubborn practices of the media deprived the voters of a debate on the central issue of the time—renewable energy—because he knew more about it than any of the other three candidates did.

With five or so weeks to go before Election Day, the Citizens Party had no money to buy advertising and was generating no news, but Bill Zimmerman, who was running the campaign, had a plan. He called Commoner and me to my apartment and pitched us a radio spot he had dreamed up while driving down the Santa Monica Freeway the previous weekend. It begins with some restaurant noise, the tinkle of a glass, and then a man says, “Bullshit!”

“What?” a shocked woman says. “Carter, Reagan, and Anderson: It’s all bullshit,” the man says. The restaurant noise fades away, and Barry Commoner comes on and says, “Too bad people have to use such strong language, but isn’t that how you feel too?” Then he goes on to make the case for the Citizens Party.

I loved it. Barry didn’t. It violated his whole idea of a campaign run on the issues. It offended his sense of dignity.

Commoner finally agreed to make the ad, provided he wouldn’t have to say the repellent word himself. Bill got an actor to say it instead. Our $700 bought one spot on CBS radio to run right before the national news came on 350 stations across the country. Bill waited for the check to clear before he sent the tape. As expected, he got a call right away, telling him, “We can’t run this. It uses a word CBS doesn’t allow on the air.” “Let’s not argue,” Bill replied. “Ask your general counsel to read Section 315 of the Federal Communications Act and call me back.” He knew that in 1934 Democrats had prohibited networks from censoring political ads in an attempt to keep Republican-owned stations from using their muscle in campaigns.

The ad ran on October 14.

“The result was spectacular,” Commoner recalled later. “In two days, the Citizens Party received more news stories and broadcast time than it had received in its entire history.” Revered CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, the Today Show, and Good Morning America all did pieces. Nearly every major newspaper in the country carried stories.

But Commoner’s reaction was more bitter than sweet. The stories were, after all, not about issues. They were about the impudence of saying “bullshit” on the air.

To some, using that term was no big deal. In his op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, Lawrence Weschler wrote about his own “unscientific random sample of public sensitivity” about the ad’s profanity. He called “at random twenty telephone numbers and asked whoever picked up to fill in the blank: ‘The presidential election campaign so far has been mainly . . .’ Three people hung up; five used words like ‘boring,’ ‘confusing,’ and ‘exasperating’; and twelve said ‘bullshit.’” But to others, including Commoner, it was a cheap stunt. He complained that the Detroit Free Press had not carried a word about his plan to revitalize the auto industry, but it had run a front-page story about the commercial. The irony hurt.

Zimmerman hustled to keep the story alive by holding press conferences that featured a rented bull. Of course, these pranks wore thin, like a joke told too many times, and ultimately had little effect. On Election Day, Barry Commoner got 234,294 votes. John Anderson won 5,720,060, almost 7 percent of the total—enough to qualify for federal funds, just as we had hoped to do.

Reagan, meanwhile, trounced Carter, carrying forty-four states and ushering in a new era of conservative leadership.

Adapted with permission from Being Dead Is Bad for Business by Stanley Weiss (Disruption Books), available Feb. 28, 2017.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com