When Harry Benson was a boy in school, he was given a Robert Louis Stevenson poem, “From a Railway Carriage,” a 19th-century evocation of watching the world fly by from the window of a train. “Here is a cart run away in the road / Lumping along with man and load;” the poem concludes. “And here is a mill and there is a river: / Each a glimpse and gone for ever!”

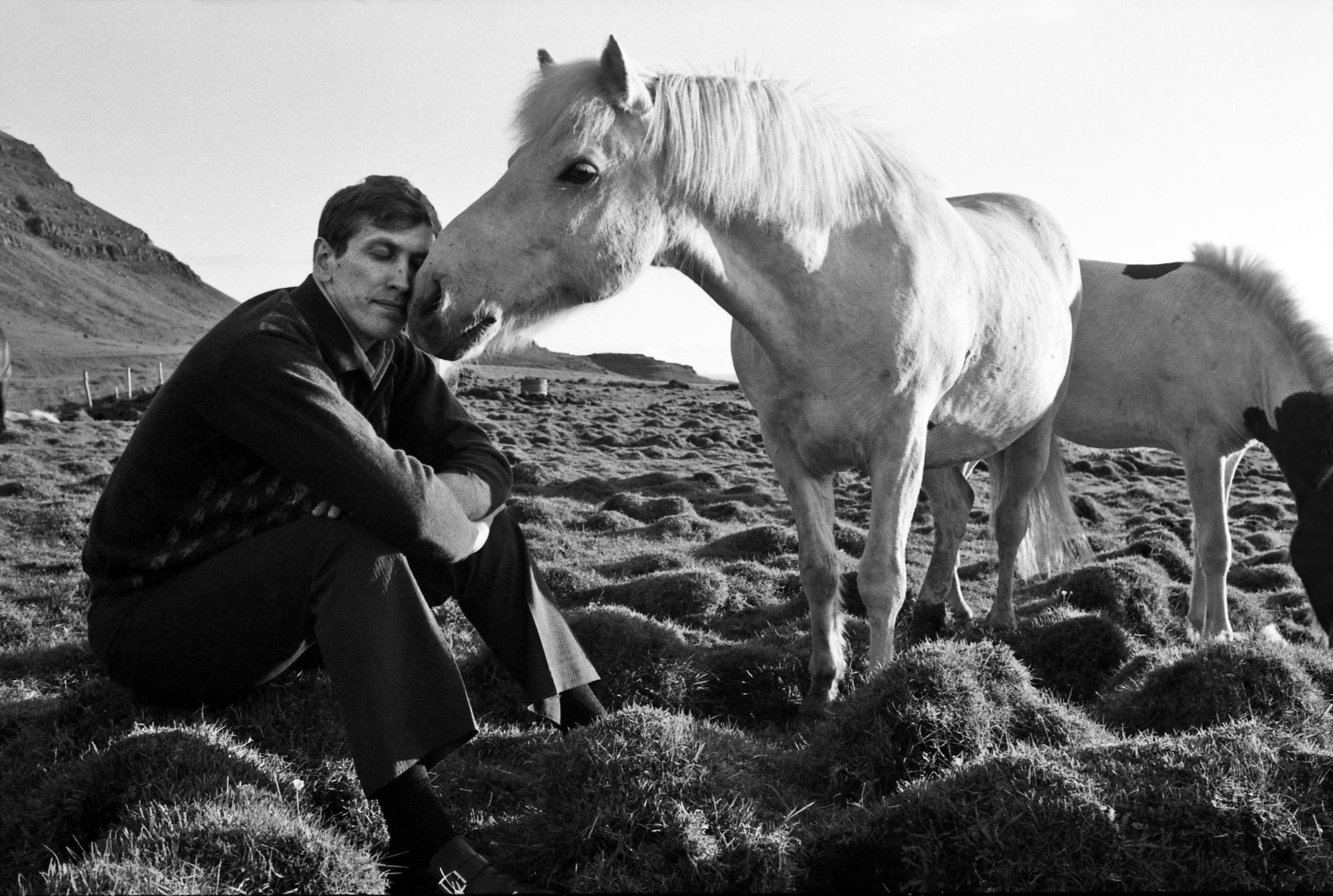

The idea stuck with the photographer, who is now 87. “To me, that’s a good photograph,” he tells TIME. “It will never happen again.”

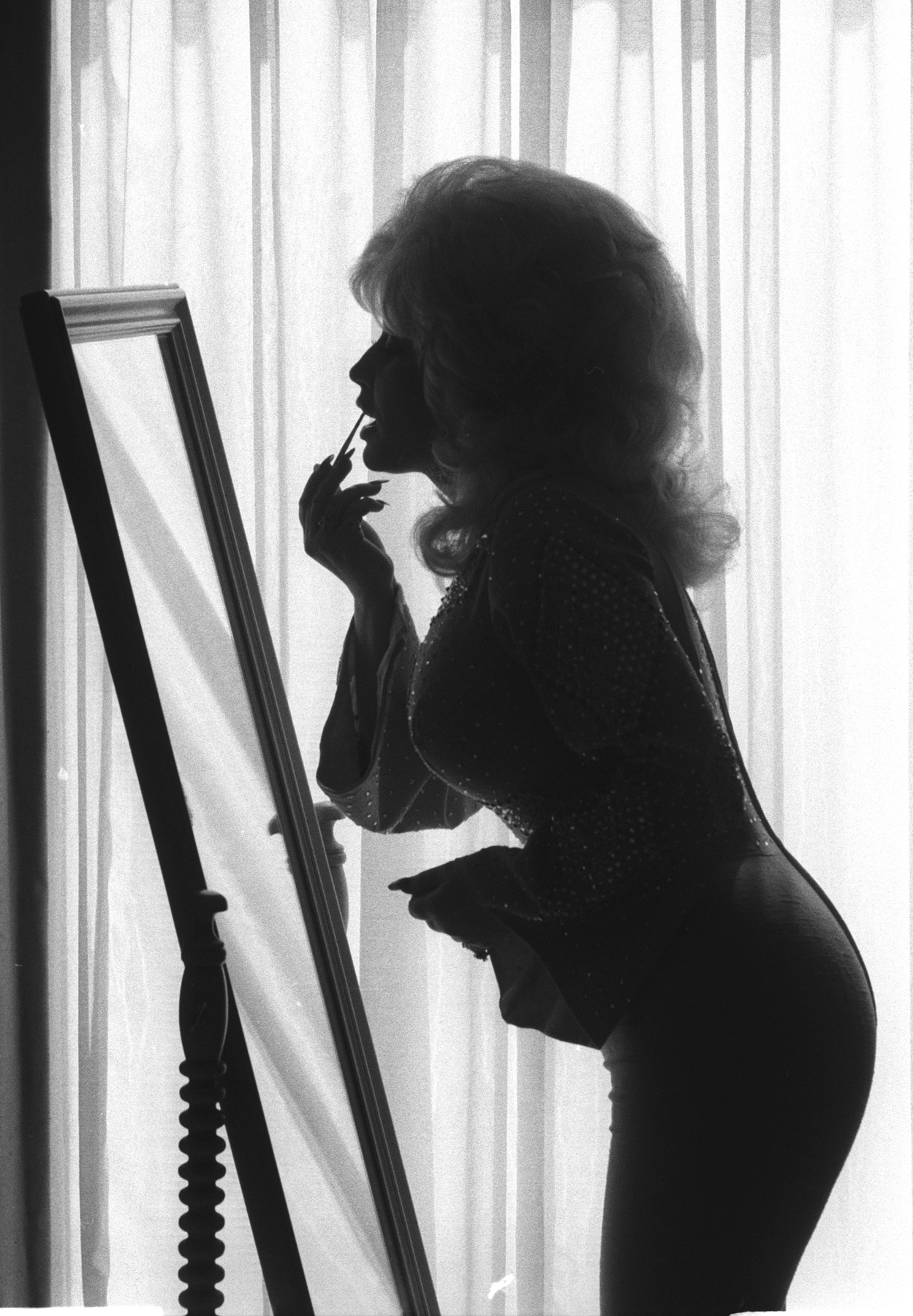

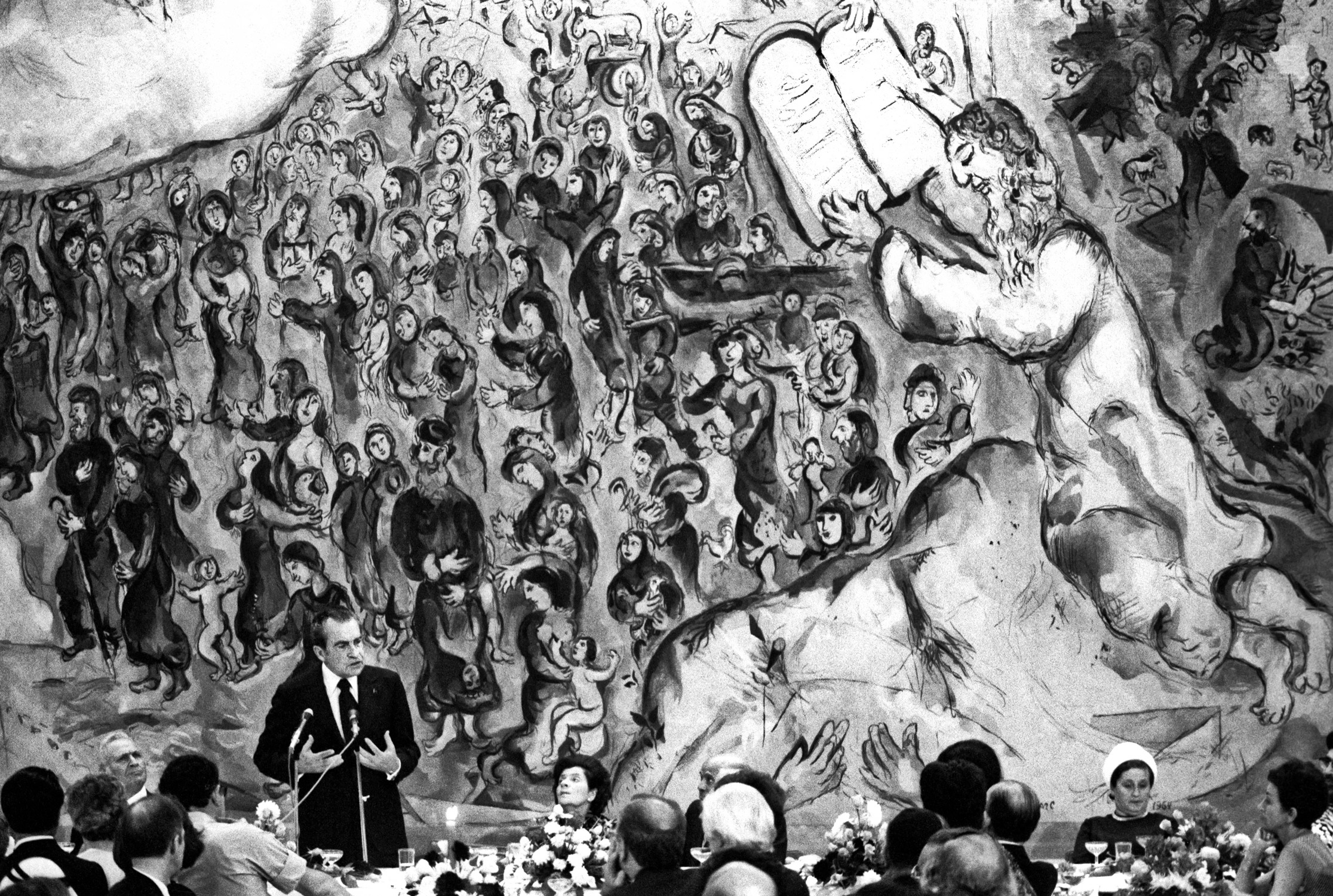

Benson’s life work is the subject of the new documentary Harry Benson: Shoot First, in theaters and on demand Friday. The film offers Benson and his subjects alike the chance to reflect on a career during which the photographer captured the 20th century in motion, as in the 10 images seen here. And after all these years, Benson says, it wasn’t easy to be the one in front of the camera rather than behind it. “I wasn’t the easiest of subjects,” he says, “because I’m used to looking at people.”

And the people he’s looked at have been, in many cases, exceptional.

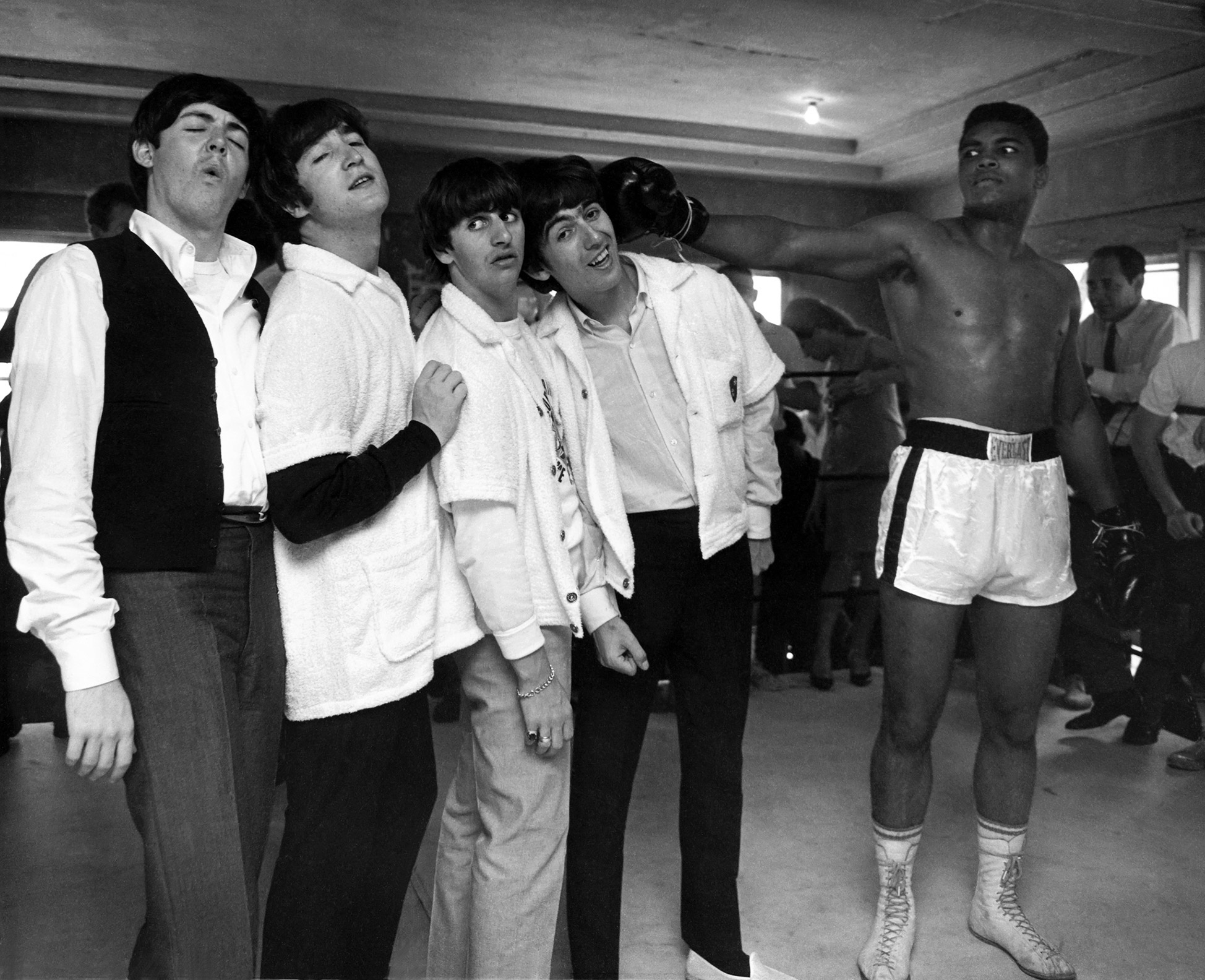

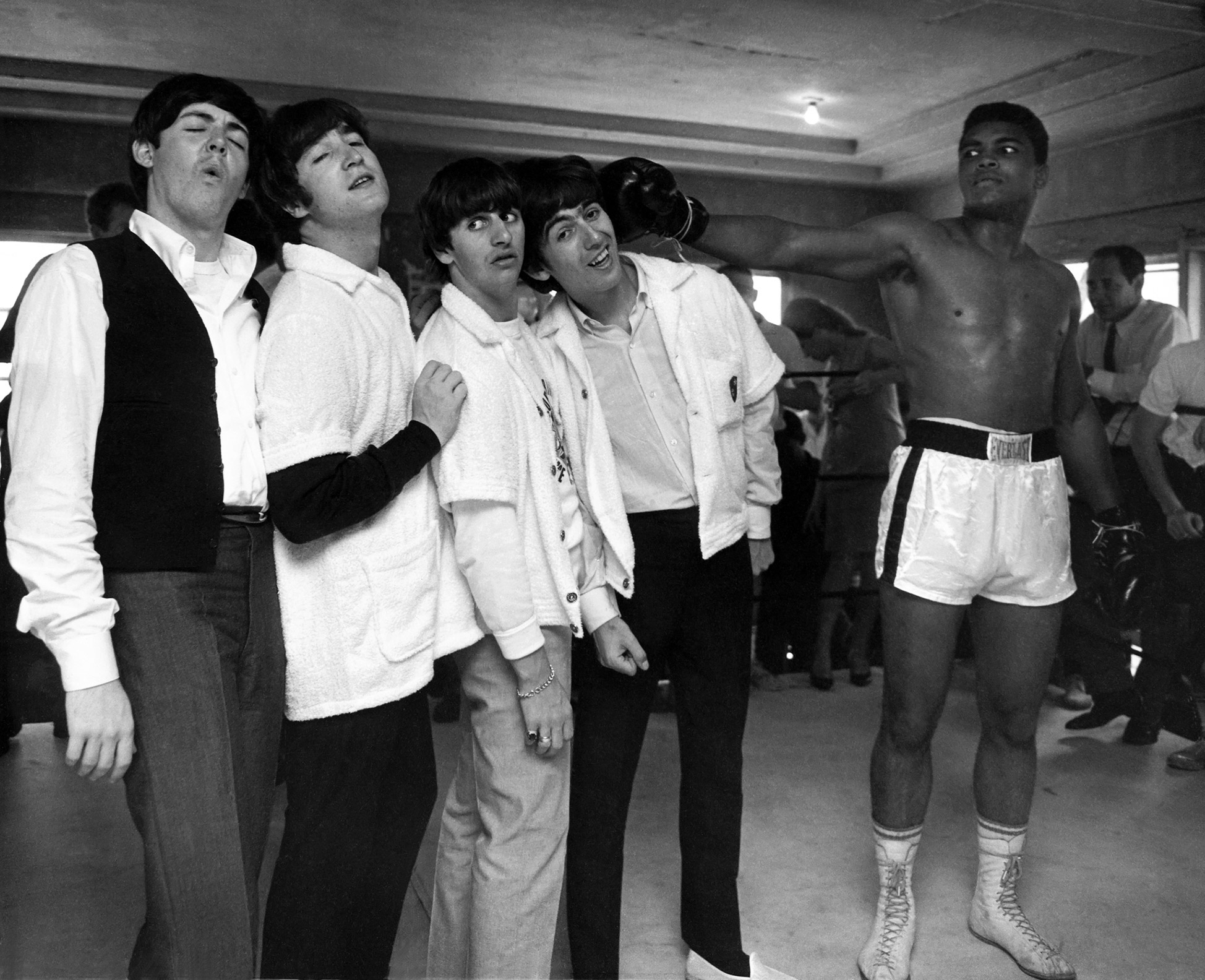

Benson made a name for himself in 1964 while photographing the Beatles during their U.S. tour, and went on to cover world news, culture and fashion for numerous publications, including LIFE. He was there the night Robert F. Kennedy was shot, and at civil-rights protests where the work got dangerous. When it comes to witnessing history, he puts it this way: Sometimes something happens and you’re not there but when you’re in a bar later, he says, you tell your friends that if you had been there you would have done this or done that. But sometimes something happens and you are there, and you know it. When that happens, you think to yourself: “Just don’t let me fail.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Ask Benson about the people he’s photographed, however, and he doesn’t necessarily have much to add. Take President-elect Donald Trump, for example. Benson has known Trump for four decades, he says, but only knows about him what he could learn from taking his picture. Benson’s work ethic could be easily mistaken for an effort toward friendship: not taking your own lunch break, he says, is the secret to getting a good photo. You have to stick around and look for the moment when the subject relaxes. But that sticking around stops as soon as the shoot is over. Make friends and you risk the subject asking for a photo not to be used, and Benson says he’d rather lose a friend than a picture.

Besides, when it comes to telling a story, what’s in the picture can be plenty to go on. “Pictures don’t lie. They don’t. And I’m not talking about Photoshopping – that’s playing about and I don’t do that,” he says. “It’s, you know, you have a picture of a baby and the caption says a picture of a beautiful baby, but you can see the baby’s ugly – that’s not the photograph that’s lying.”

The photograph is true, and—if it’s a good one, by Benson’s estimation—it captures something that will never happen again. That means it’s a special way of capturing history, but also a special way of looking to the future. Having spent the documentary filming process reflecting on his own work, that fact is clearer than ever to Benson.

“I just think to myself, well, that was a good picture, and I move on to what’s happening today,” he says. “The thing about photography, which is wonderful about it, is every day is a new day.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com