“Mayday!” came the frantic call from inside the tiny U.S. military attack helicopter after a rocket-propelled grenade fired by an al Qaeda-linked Iraqi lopped off its tail rotor and forced it to crash land in the desert 20 miles northwest of Baghdad. A fierce firefight soon broke out as the insurgents headed toward their prize: the downed AH-6 Little Bird chopper, and about 20 U.S. soldiers, including members of the secret Delta Force, who’d landed to protect it. But just like the cavalry used to ride to the rescue, Air Force Major Troy Gilbert miraculously appeared from over the horizon. The militants were too close to civilians and friendly forces for bombs, so Gilbert screamed in fast and low—200 feet above the desert—and shredded the first truck with the six-barreled Gatling gun tucked into the left side of his F-16. He roared into a tight right turn and opened up again, his eyes glued to the second truck. But at 500 miles an hour, he stuck a second too long. His jet left its imprint on the desert sand like a bare foot on a wet beach, and bounced 600 yards before disintegrating amid a carrot field.

At the cost of his own life, Gilbert’s daring helped save his fellow Americans on Nov. 27, 2006. But by the time the clash ended and U.S. troops made it to the crash scene, Gilbert was gone. U.S. officers had seen, via a video feed from a drone far above, al Qaeda fighters pull Gilbert’s body from the wreckage, roll it up in a carpet, and stash it inside a truck. The Army stormed five nearby buildings where they suspected Gilbert’s remains had been taken, but came up empty.

Advances in identifying remains, and a paucity of major battles, have shrunk the number of U.S. troops declared missing in action in recent wars. With Gilbert’s return, there are no American MIAs remaining in Iraq or Afghanistan. There are 126 MIAs from 14 Cold War clashes (most involving shoot downs over water); 1,618 from Vietnam; 7,780 from Korea; and more than 73,000 from World War II.

Since that day a decade ago, Major Gilbert had come home twice, but only in bits and pieces. In December, his full body will finally be laid to rest. He will be the first person, according to the records of Arlington National Cemetery, ever to be buried in the nation’s most hallowed grounds three times.

His is a story of heroism, tempered by heartbreak, and horror. But most importantly, it’s a story about coming home. It’s a powerful testament to the Defense Department’s pledge—embraced by everyone wearing a U.S. military uniform headed into harm’s way—to never leave a comrade behind. While many of the details of Gilbert’s case remain classified, the story that follows has been gleaned from official and unofficial military accounts, Gilbert’s family, and members of the U.S. military who believe it is one worth sharing. “The lesson for everybody who hears this story is that we don’t give up,” Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James tells TIME. “We bring them home.”

Gilbert, 34 when he died, was the son of Air Force Senior Master Sergeant Ron Gilbert, an enlisted man, and his wife, Kaye. He was born on an Air Force base in Louisiana and always wanted to fly. In one treasured family photo, he’s the only member of his Little League team not staring at the camera. He was craning his 10-year-old neck, transfixed by a T-38 jet trainer overhead when the family lived at an Air Force training base in Del Rio, Texas. “Anytime we were outside, his eyes were always up looking at the sky,” his younger sister, Rhonda Jimmerson, says. “His favorite movie growing up was Top Gun.”

He married Ginger, his college sweetheart, after their Texas Tech graduation in 1993. During his 12 years in uniform, he was what the service calls a “fast burner,” training Air Force pilots in Arizona, helping to keep Air Force One flying as a logistics officer, and tapped to attend the Army Command and General Staff College in Kansas after his Iraq tour. He picked up his call sign—”Trojan”— while flying F-16s out of Aviano, Italy. By the time he shipped out to Iraq in September 2006, he and Ginger had five kids, including identical twin daughters born six months earlier. The couple discussed his decision to volunteer for the assignment. “If something happens to you, we’re never going to forgive ourselves,” she told him. “Nothing’s going to happen to me,” he assured her. “I am a pilot.”

Eleven days before his final mission, Gilbert recorded a video to send home for the family to watch at Christmas. “I will stay safe, and I will stay healthy, and I want you guys to do the same,” he said while sitting in his room in an Air Force T-shirt. “I love you guys, and I can’t wait to see you.”

Gilbert and his wingman had been flying about three hours when the chopper went down just after noon. It was Gilbert’s 22nd Iraq mission. The helicopter’s two crew members belonged to the Army’s Task Force 160 Night Stalkers, the same outfit that would take Navy SEALs for their final rendezvous with Osama bin Laden five years later. It was one of six helicopters seeking to kill or capture a local al-Qaeda leader near Taji. Troops from the other helicopters landed and came to the pilots’ aid and to protect the unflyable Little Bird. But after the wounded pilots had been flown to safety, those left behind soon found themselves under heavy attack. Mortars, RPGs and rounds from anti-aircraft guns and AK-47s began raining down, fired by al Qaeda-linked insurgents. There was no place for the troops to hide. The surviving AH-6 returned to the air to fight.

The airwaves crackled with radio calls from the ground seeking more help as Gilbert arrived on the scene. “We had called our people, our command, and requested tank support, helicopter support, anything to help us because we were being overrun,” the radioman on the ground—the last person ever to speak to Gilbert—said, according to Gilbert’s father. “Nobody would help us—they couldn’t get in because it was too hot,” Ron Gilbert recalled the Delta Force commando telling him three years ago during a visit to Delta Force’s secret Fort Bragg, N.C., compound.

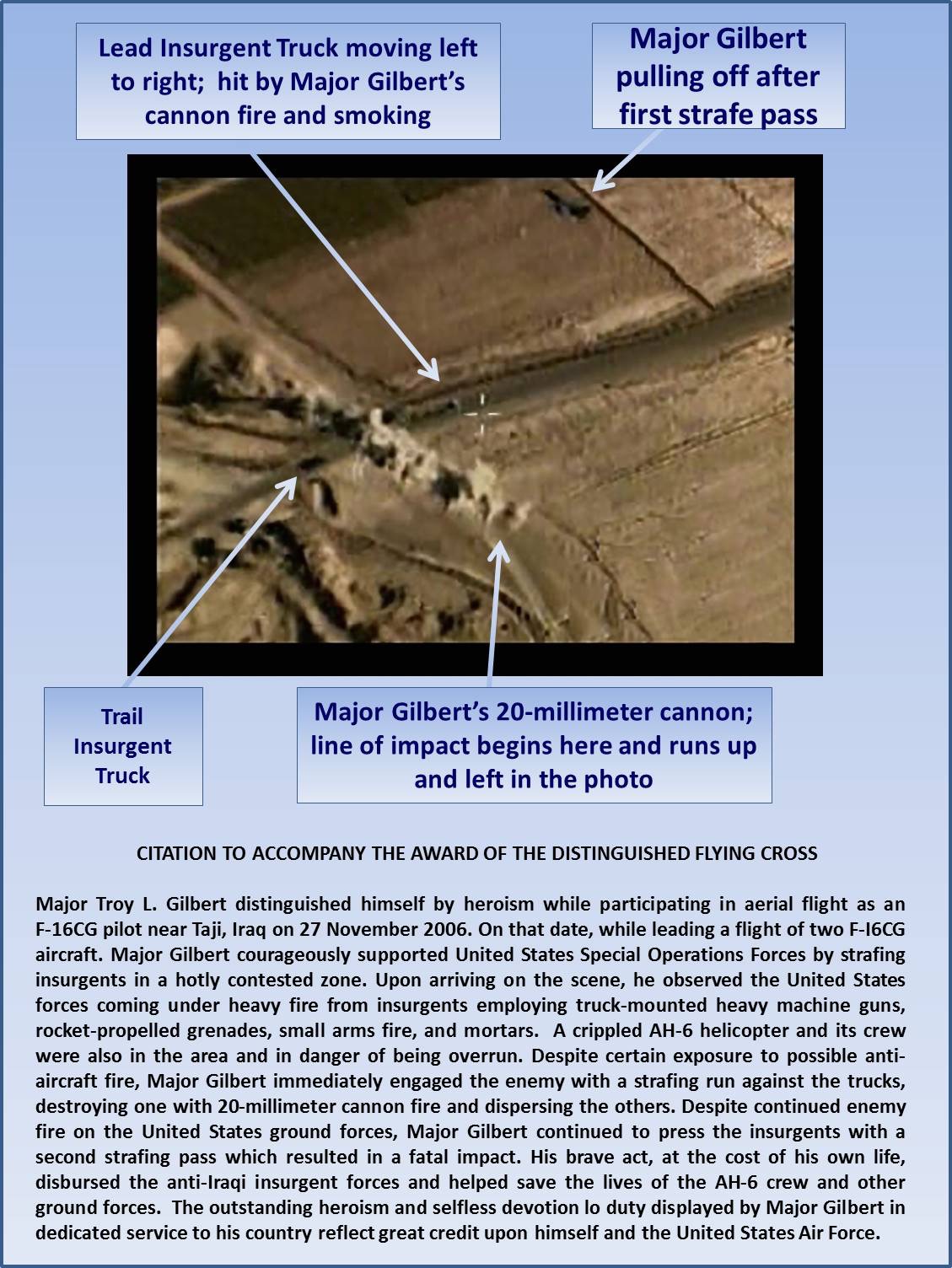

Gilbert spied a pair of trucks outfitted with machine guns and RPG launchers threatening the stranded Americans. Fueled by both JP-8 jet fuel and adrenaline, Gilbert rolled in on his first strafing run and targeted the lead truck. He held in a steady dive from 1,300 to 900 feet as he fired, before beginning to climb at 200 feet. Betty, as the cockpit warning system is called, blared “Pull up!” into Gilbert’s headset as warnings flashed on his heads-up display. In pilot parlance, Gilbert had “padlocked” onto his targets, so intent on completing his mission he ignored danger to himself. “He had to act quickly, within a matter of seconds,” says his oldest child, Boston, now 19 and a freshman at Southern Methodist University. “Knowing him, there was no other option.”

Gilbert circled back for another pass, firing two bursts at the second truck while diving from 1,000 to 700 feet. Again, warnings sounded inside the cockpit. A fifth of a second after releasing the trigger, he began pulling as hard as he could on the control stick to regain altitude. But it was too late: he had run out of sky. The F-16 was pointing up when it slammed tail-first into the ground less than a second later. The impact (with a force up to 795 times that of gravity, 10 times what is survivable) threw the plane’s engine nearly a mile.

“We saw a huge fireball,” says one soldier who was there. “We didn’t know what had happened.” But as radio calls for Trojan went unanswered, it soon became clear.

“This motivation to immediately support friendly forces under fire produced a series of decisions and flight parameters that left little room for recovery on the first strafe pass, and no possibility of recovery on the second pass,” the official Air Force investigation into the crash concluded. Gilbert died, it added, because of his “excessive motivation to succeed.”

The grunts appreciated his sacrifice. “We were in a very vulnerable position on the ground and in great danger of having heavy casualties inflicted upon us,” an Army officer wrote Gilbert’s commander. “It was obvious to all of us on the ground that he was single-handedly breaking apart the enemy forces.” Because of the fighting, U.S. forces didn’t get to the crash scene for eight hours. “No body was found by those securing the crash site,” the Air Force investigation said.

Delta Force acknowledged its debt. There’s a plaque in his honor inside that Delta Force compound, and the Air Force posthumously awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross with Valor. Fellow pilots took it hard. “I knelt by this pool of blood and prayed for the family,” says one who arrived on the crash site the next day. “I knew he was gone.”

A 30-vehicle Army convoy arrived with orders to secure the scene and find Gilbert. A search dog found the carpet used to carry the pilot away, but not him. “There was a constant anger: where is our guy?” recalls Michael Stevens, an Army private who spent five days at the crash scene. “We’re not sleeping for days on end, trying to find any hint of him, but there was nothing to find.”

The whole area, in fact, seemed to have turned into a ghost town after the crash. “There was a lot more houses than people, which was wrong,” Stevens says. And the few locals still around were no help. “Everybody was lying; obviously lying,” he adds. “They were very afraid, but they didn’t seem as afraid of us as the people who were hiding the body.” When the Americans recovered a bloody blanket outside one house, the woman who lived there pleaded ignorance. “The lady wouldn’t talk about it—she said `I don’t know why that’s there.'”

Daughter Bella, now 13, was bouncing on a trampoline in the back yard of the Gilberts’ Phoenix home when Ginger heard a knock on the front door. “There was this whole sea of Air Force uniforms and I think, `That’s strange,’ for about a second and then you think that cannot be what they’re here for because that wouldn’t happen.” They delivered the grim news. Within hours they had discovered enough skull fragments and tissue to know that Trojan hadn’t survived. The Pentagon changed Gilbert’s military status from “DUSTWUN”—Duty Status Whereabouts Unknown—to Killed in Action.

But 99% of his whereabouts still remained unknown.

Gilbert’s first burial took place at Arlington on Dec. 11, 2006. About 300 mourners said their final goodbyes accompanied by military ritual: a horse-drawn caisson, taps, and an F-16 flyover.

“I remember walking behind the caisson with my little kids and feeling like, `I know he’s not in there,'” Ginger recalls. “Everybody knew he wasn’t in there, except my children. I mean, there was one small, tiny, tiny little piece, but I didn’t want them to know, because how to you explain that to your little kids?”

There were more sad and bitter moments to come. Six months after his death, Ginger and their sons traveled to Arlington to be with him on their wedding anniversary, the same week as Memorial Day. “I couldn’t think of any place else I was supposed to be at that time of year,” Ginger says.

Then, on the first September 11 after his death, an al Qaeda website posted a video of Gilbert’s body, along with footage from the crash scene. While it didn’t show his face, it showed his pristine ID card. “They were using his body as propaganda and as a war trophy,” Rhonda says. The video blamed President George W. Bush for dispatching Gilbert and “thousands of American soldiers to the incinerator in Iraq.”

But there were brighter spots, too. In 2008, Ginger married Jim Ravella, a retired F-15 pilot who had lost his wife to breast cancer. Ravella adopted Troy’s five children on Memorial Day 2009. The Gilberts say it was their evangelical Christian faith that sustained them during the fruitless years of searching. Ginger and Jim now work for Folds of Honor, a non-profit that provides scholarships to the children and spouses of fallen or disabled troops.

Meanwhile a 20-member team of retired Special Forces and intel analysts was spending years vainly scouring Anbar province. “We devoted thousands of hours attempting to find him,” one military searcher wrote the Gilberts. “Someone out there knows where he is buried.” The U.S. government, he said, offered a “hefty” (“even in America”) but classified cash reward for information leading to his return. It broadcast frequent TV commercials seeking his whereabouts. One 2011 mission involved dispatching 160 soldiers and cadaver dogs in 24 vehicles, along with a backhoe and Predator drone overhead, to a farm where a half-dozen disturbed-soil sites were vainly dug up in 104-degree heat. “Any one of my team, including myself, would gladly go into the worst parts of Iraq and face any threat in order to get Troy back,” the military searcher added. “It was our job, and it’s what we owe to every American.”

But the military bureaucracy kicked into high gear as it prepared to pull out of Iraq at the end of 2011. It let the family know the search for Troy would end at the same time. “The Air Force told us `He has been accounted for, we have his remains, he has been identified, and he has been buried with honors at Arlington National Cemetery. So there is nothing more to do—the case is closed,'” Rhonda recalls. But she adds that the “heart-wrenching and crushing” al Qaeda video showed otherwise: “I was able to use that video and say: `No, he’s not accounted for, and here’s the proof.'”

The Gilberts met with their congressman, Mac Thornberry, a senior Republican member of the House Armed Services Committee. “We told him they wouldn’t listen to us,” Ron recalls. “He got really mad and said, `I’ll tell you what: they may not listen to you, but they’ll listen to me.'” (Thornberry declined to be interviewed). “As a mother, I carried the whole man inside of me,” Kaye says. “I raised the whole man for 17 years. And he was a whole man when the Air Force took him to Iraq. I wanted a whole man back.” Soon enough, the Pentagon did an about-face. “His family deserves nothing less than our best effort to recover his remains and return them to his loved ones,” then-Air Force Secretary Michael Donley said in February 2012.

It was ultimately an Iraqi who provided Gilbert’s second set of remains. He turned over bones from the tip of each toe of Gilbert’s right foot to the Jordanian embassy in Baghdad late 2012, which handed them over to the Americans. Intelligence suggested that Gilbert’s body was being moved—maybe even stolen—among tribal leaders in western Iraq. “We would get close to finding him and somebody would move him,” Ginger says. “Those would have been the first things that broke off in moving a skeleton.”

Once the bones were confirmed as Troy’s, the military spent nine months searching for the rest of him before telling the Gilberts what they had found. The Iraqi “led them on a wild goose chase of grave sites saying that he knew where Troy was,” Ginger’s husband Jim says. “They didn’t want to inform Ginger because they thought were going to get all of Troy.” But once again, the trail went cold.

Ginger told her children about their father’s fate as they grew older, but hadn’t yet told the 7-year-old twins when the toe bones came home in 2013. Unsurprisingly, they were confused: “They were like, `What? We’ve already buried him.'”

On Dec. 11, 2013, about 150 people returned to Arlington as a small box carrying those bone fragments was placed alongside the original casket, buried seven years earlier, to the day. Ginger and the children placed red roses next to the box. A bagpiper played Amazing Grace, and a bugler sounded taps for Major Gilbert for a second time.

The odds of bringing Gilbert home faded. The 150,000 U.S. troops that had been swarming all over Iraq in the three years after the crash had dwindled to hundreds after the U.S. pulled out in 2011. But as more Americans returned to Iraq to battle ISIS—there are more than 5,000 there now—one Iraqi shared a critical piece of intelligence. He reported that a tribal chieftain near Fallujah was saying that he was the latest local leader to have custody of an American pilot’s body. “We learned that his body had been moved several times,” Ron says. “He was like a trophy, going from tribal leader to tribal leader.”

U.S. troops, including members of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, paid the chieftain a discreet visit. They demanded proof of his claim, and he turned over a jaw bone on August 28. Ten days later, the mortuary at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware confirmed it was Gilbert’s.

On the night of Sept. 30, a 29-member team, including personnel from Task Force 160—the same unit that Gilbert died protecting—paid the chieftain a second visit. “We knew we couldn’t fumble this mission—they could have been sucking us into a trap,” says a U.S. Central Command officer. “So we had to go in big”—with enough firepower to assure success. They demanded he turn over Gilbert’s body, but he initially refused. “They said he didn’t have a choice, and if he didn’t give them the body, he’d regret it,” Ron says. After considering his options, the chieftain relented. “They went and dug him up, along with his flight suit and part of the parachute.”

Bella was a 3-year-old toddler bouncing on her backyard trampoline when the family learned her father had gone down 10 years before. In October, she was a 13-year old teenager playing in a volleyball tournament when her mother got the phone call that ended the family’s quest. “They’ve found Troy,” Air Force General Robin Rand, a family friend, told her from a quiet corner of the Air Force Academy’s Falcon Stadium (where the Air Force football team was beating Navy, 28-14). “Did they get all of him?” she asked from inside her SUV in San Antonio, where the family now lives. “Because you know it’s just never been over.”

“All of him,” Rand told her. In fact, her late husband and the father of their five children had been placed aboard a C-130 cargo plane that had been standing by in Baghdad, and was headed for Germany, and ultimately home, within hours of his recovery.

At twilight on October 3, Major Troy Gilbert landed at Dover aboard a C-17, where his family and top Air Force officials welcomed him home. Included in the solemn gathering was James, the Air Force secretary, as well as four-star General David Goldfein, who as chief of staff is the service’s top officer. A decade ago, as a one-star brigadier general, he had led the investigation into Gilbert’s crash. Six airmen in battle fatigues, combat boots and white gloves slowly moved his casket from inside the cavernous cargo plane to a waiting hearse.

After nearly a decade, the Gilberts are finally able to awaken from their nightmare. “It’s really hard to go through three funerals,” said his mother, who was at Dover when her only son finally came home. “I know that.” Even so, she is looking forward to saying her final goodbye during his third burial at Arlington, on Dec. 19 at 1 p.m. “It is going to be,” she says, “a joyous day.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com