This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

For the last week, stories on President-Elect Trump’s potential cabinet nominees have filled the news, and with good reason. Cabinet secretaries exercise enormous power—they define and enforce policy with a great degree of autonomy. Yet none of these stories mention the fact that the Constitution did not create the cabinet, nor did Congress authorize it through legislation. In fact, no legal authority establishes the cabinet as an advisory body or regulates the relationship between the secretaries and President.

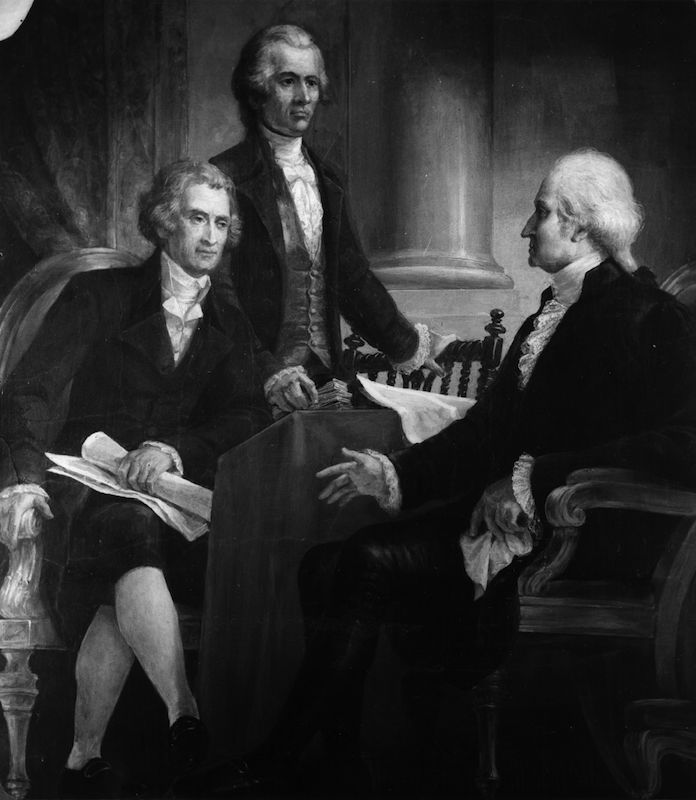

The cabinet’s absence from the nation’s governing documents was no mistake. During the Federal Constitutional Convention in 1787, the delegates rejected proposals that would have created a privy council to advise the President. Instead, they adopted Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, which provides two options for the president to obtain advice. First, the President can request written advice from the department secretaries. Second, the President can consult with the Senate on foreign affairs. The Constitution, a document of enumerated powers, does not provide any other means for the President to obtain advice from government officials.

By limiting the President to written communications with the department secretaries, the delegates sought to increase transparency in the executive branch and ensure that each official took responsibility for their political positions. During the Revolutionary War, when the Departments of Finance, Foreign Affairs, and War first developed, the department secretaries served as agency heads who reported to the Continental Congress. The delegates expected the secretaries to continue overseeing their departments and to report formally to the President—not to convene as a body of advisors. The delegates preferred the Senate, an elected body, to play the primary role of advising the President on diplomatic matters, and did not want to cede this advisory responsibility to the department secretaries.

President George Washington initially limited himself to the two options outlined in the Constitution. On August 22, 1789, he visited the Senate for the first time. Washington planned to send commissioners to a summit in September 1789 to negotiate with representatives from the Carolinas and the Cherokee and Choctaw nations. Because Washington had never authorized federal commissioners before, he wanted the Senate’s advice on how he should frame his instructions. He brought a series of questions for the senators to consider and expected them to debate the issues and provide their individual opinions on the Senate floor. Instead, the Senators shuffled their papers, cleared their throats, and sat in awkward silence. Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania believed that the Senators were too intimidated by Washington’s presence to respond, so he proposed that they refer the matter to committee for further discussion. Washington was furious. Abandoning his famous reserve, he yelled, “this defeats every purpose of my coming here!” Washington concluded that the Senate was too large and cumbersome to provide the timely advice that effective diplomacy demands, and he never returned to seek its advice again.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Shortly after his inauguration, Washington also requested written advice from the department secretaries, but he quickly discovered that the issues facing the administration were too complex to resolve through written correspondence. Washington began inching toward a cabinet in 1790, when he requested follow-up meetings with individual department secretaries after they submitted written opinions. In 1791, Washington took the next step when he departed Philadelphia—then the seat of government—for a tour of the southern states. Washington authorized the secretaries to meet in his absence if an urgent matter should arise. In November 1791, he summoned his first cabinet meeting to review commercial treaties with France and Great Britain. Over the next year, Washington convened a handful of cabinet meetings, but continued to handle the majority of government business in conferences with individual secretaries. In April 1793—a watershed moment for cabinet development—Washington summoned regular cabinet meetings for the first time as France and Great Britain threatened to drag the United States into their European war. Over the next year, the cabinet met as frequently as five times per week to establish rules of neutrality, determine how to enforce neutral policy, and decide how to engage with hostile European powers. After 1793, the cabinet remained a central part of the executive branch for the duration of Washington’s administration.

As with many of the policies set in Washington’s administration, his cabinet precedent continues to shape modern presidential politics. Although the executive branch and the cabinet have both expanded since the 1790s, each President—like Washington—has the power to select his own advisors and decide how often and in what capacity they will interact. In some administrations, such as the Lincoln and Obama administrations, the department secretaries served as the President’s most trusted advisors. In others, like the Jackson or Kennedy administrations, the President preferred other counselors. Although the delegates to the Constitutional Convention may not have wished it so, the cabinet has become a flexible institution that serves at the pleasure of the President.

We are only one week into President-Elect Trump’s transition, but already his hiring decisions have stirred up significant controversy in the press and on social media. Yet, this controversy is merely a reflection of the system built by Washington, in which the President has nearly unchecked power to select his own advisors. After Trump announces his nominees, the Senate must approve the fifteen department heads. But, the Senate has rejected only six cabinet nominees since the 1790s. The Senate’s first rejection was in 1834 when President Andrew Jackson nominated Attorney General Roger Taney to be Treasury Secretary. The most recent rejection occurred in 1989 when the Senate opposed President George H.W. Bush’s nomination of John G. Tower to be Secretary of Defense. More often, Presidents have withdrawn a nominee when confirmation has seemed unlikely.

After the Senate approves President-Elect Trump’s nominees, the secretaries will largely operate independently and without supervision. The Constitution grants the public very little oversight. Congress can call for investigations into departments and, as a very last resort, impeach a department secretary. In practice, though, such an event is unlikely. The House of Representatives has initiated only nine impeachment proceedings of department secretaries. The House unanimously impeached President U.S. Grant’s Secretary of War, William Belknap, in 1876, but the other eight proceedings either died in committee or the secretary resigned prior to impeachment.

Other advisors are further outside the reach of public oversight. For example, Trump has already selected a Chief-of-Staff, Reince Priebus, and a Chief Strategist, Stephen Bannon. The Constitution does not define either of these positions. They are not subject to approval by any other branch of government—not the Senate, not the House, and not the people through direct election. The media attention devoted to these staff selections, as well as the department secretary nominees, reflects the public’s widespread concern that these appointments are not subject to the vigorous vetting one might expect of an official with top-secret security clearance. This process also demonstrates that, while many aspects of the executive branch would be unrecognizable to the founding generation, the President’s selection of his own advisors would be quite familiar thanks to the precedent established during Washington’s administration.

Lindsay M. Chervinsky is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of California, Davis.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com