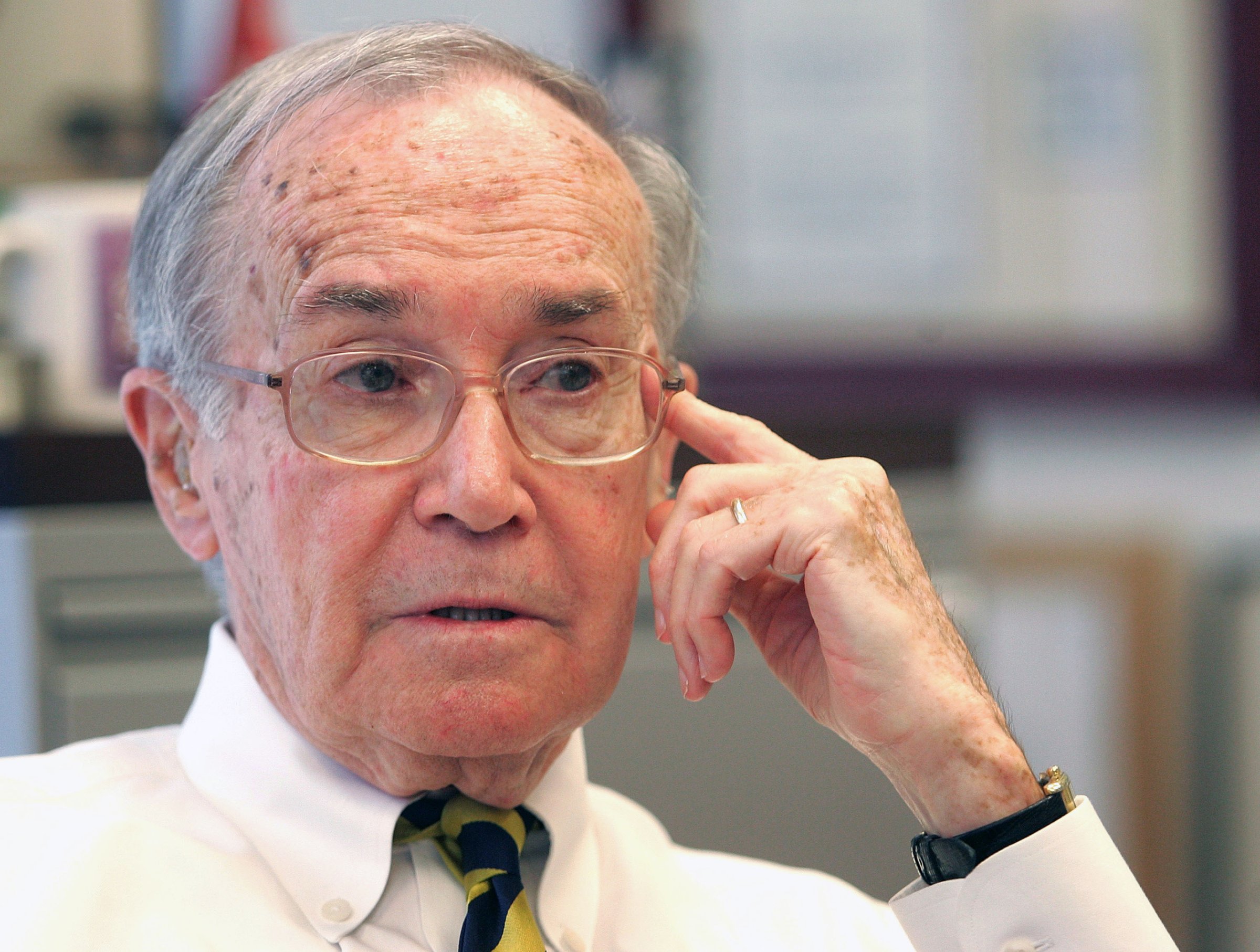

When President Obama steps into the East Room of the White House on Tuesday and awards the Presidential Medal of Freedom, our nation’s highest civilian honor, one of the recipients, along with Bruce Springsteen, Diana Ross, Michael Jordan, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Tom Hanks, will be a less well-known, but no less deserving honoree, Newton Minow. Minow is being recognized for a lifetime of public service, from serving as John F. Kennedy’s Chairman of the FCC, to fathering the modern presidential debates to a long career as a civic-minded lawyer in Chicago.

Minow’s life and legacy would be worth celebrating at any moment in our history. But in the aftermath of the 2016 election, when Hillary Clinton herself conceded that we are “more deeply divided than we thought,” and many Americans are concerned about how the incoming president will govern in the White House, it’s important to reflect not just on Minow’s legacy, but on the legacy of his generation of public servants and in particular, Democrats.

Minow is one of the last surviving members of a generation of Democrats, many of whom became nationally known in the 1960s as the New Frontiersmen. During Obama’s two terms, we lost many of them, from the Lion of the Senate Ted Kennedy himself to Ted Sorensen, Kennedy’s legendary speechwriter and close advisor.

I’ve had the privilege of knowing many of these New Frontiersmen. In addition to being Minow’s great nephew, I helped Ted Sorensen write his memoirs before following as best I could in Ted’s footsteps and joining Obama’s fledgling campaign as a speechwriter in the early days of 2007.

Their brand of American idealism and generational devotion to public service may seem outdated today, forged as it was in the cauldrons of the Great Depression and World War II more than 70 years ago, decades before public and personal scandals and failures—from Vietnam to Watergate, Impeachment to Iraq—shattered the American people’s trust in government and the men and women who lead it.

And yet, there is still much we can learn from the New Frontiersmen about the necessity of national unity, the imperatives of conscience and the demands of courage.

First, the necessity of national unity. For their generation of Americans, national unity was not simply a political strategy or a sound bite. It had been, in recent memory, the salvation of the country during the Second World War, where many New Frontiersmen, including Minow himself, served overseas. Fighting alongside Americans from different ethnic, religious and economic backgrounds they might have never otherwise met, the experience cemented their allegiance to a common good that transcended any political differences. Kennedy’s inaugural address itself was an ode to the idea that the national interest places certain requirements on us as citizens that are more important than political preferences. “Sometimes,” as Kennedy himself said, “party asks too much.” That idea is something we have lost, and something we need to reclaim.

Second, the imperatives of conscience. From partnering with Martin Luther King Jr. on the fight for civil rights—what Kennedy called “a moral issue as old as the scriptures” —to the anti-war candidacy of his brother Robert, whose brief 1968 campaign shined a light on the scourge of Appalachian poverty, the New Frontiersmen recognized that federal and state policy are more than instruments of government, they are expressions of our values. And while the New Frontiersmen knew that democracy requires compromising on issues, they also warned against compromising our principles. “We can compromise our political positions,” as Kennedy put it, “but not ourselves.”

Third, the demands of courage. Neither of the first two imperatives—rejecting political preferences in favor of the national interest and acting in a way that is consistent with our conscience—is easy. Each of them requires courage, the subject of Kennedy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, where he argued that a democracy that has no profiles in courage “in a sea of popular rule is not worthy to bear the name.” Minow himself was such a profile in courage, walking into a meeting of the National Association of Broadcasters in 1961, as the 35-year-old Chairman of the FCC, and declaring that television, the source of his audience’s power and profits, was a “vast wasteland,” and reminding them of their responsibility to develop programming that not only drove ratings, but educated viewers, an injunction that is even more relevant to all technology and media companies today.

Tuesday marks 53 years since we lost President Kennedy. Today, Americans are more cynical, more fractured, and more wary of false promises and government overreach than the New Frontiersmen of the 1960s. And our democracy is buckling under an array of structural challenges that have emerged since that time, from the corrosive influence of money in politics to gerrymandered districts that promote polarization to a fragmented media, rife with fake news, that is amplifying and aggravating the worst strains in all of us. Rescuing and renewing American democracy will mean overcoming these challenges, and that will take time. But as we begin that work and navigate the months and years ahead, we would do well to be guided by the qualities of leadership that defined New Frontiersmen like Newt Minow.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com