I always loved Leonard Cohen’s music. Once, I went on a date with him.

I’d been complaining about my love life to Rufus Wainwright and his husband Jörn Weisbrodt—I’d just been through a bad breakup—and they said, “Why don’t you go out to dinner with Leonard? He’s single.” Rufus knew Cohen from Montreal, so he phoned him and asked.

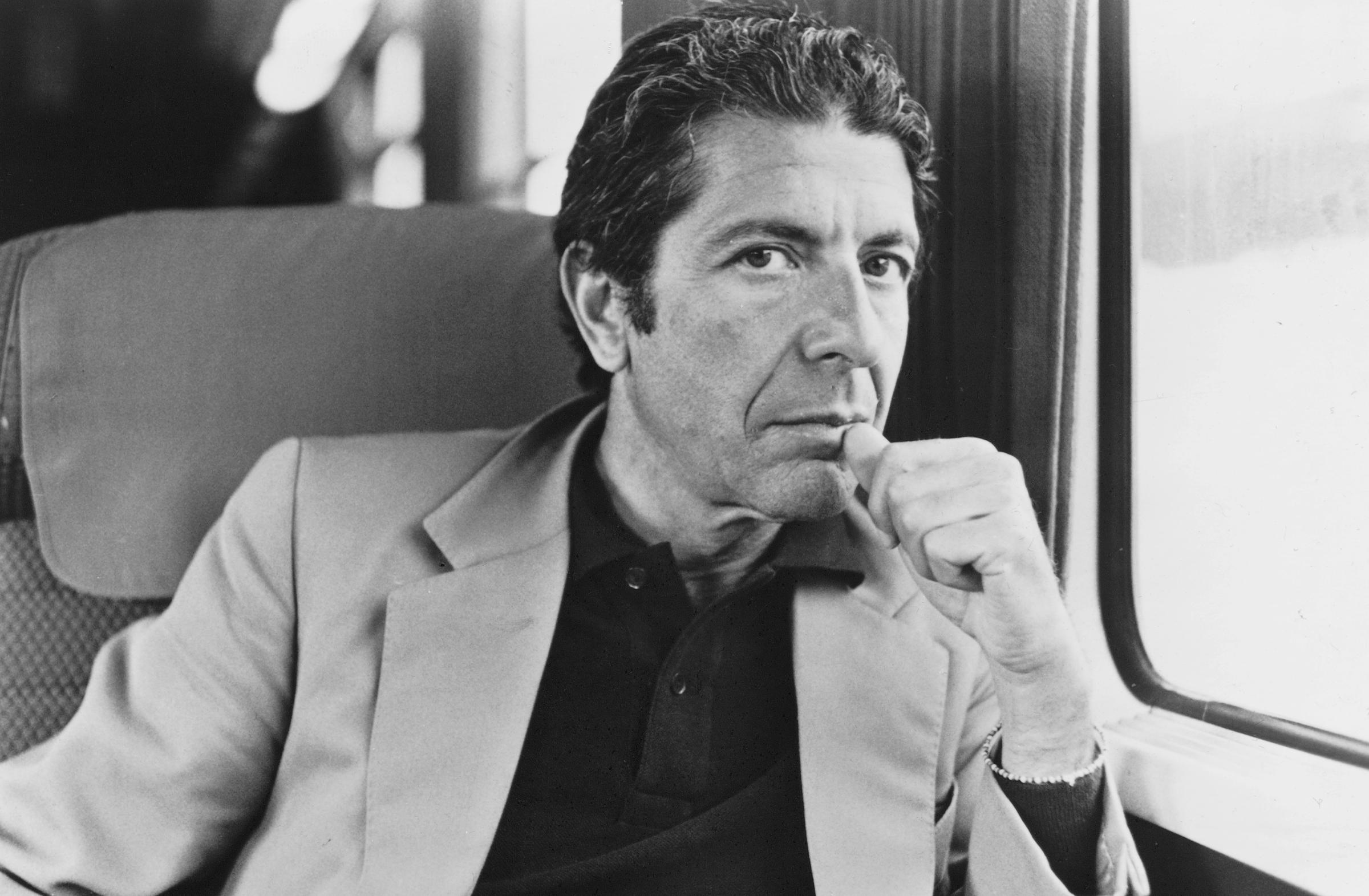

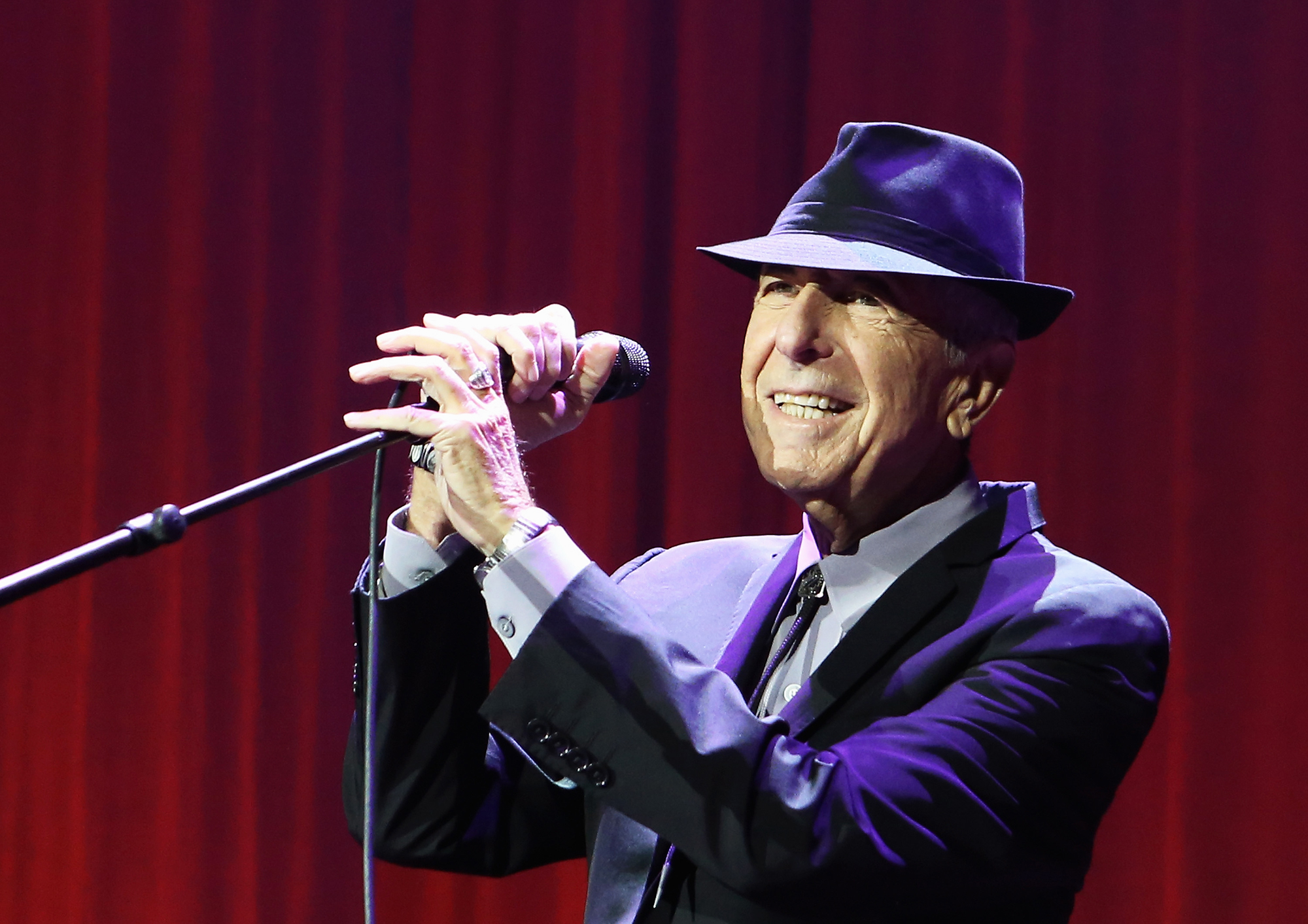

It happened that I was traveling to Los Angeles for my work, so it was perfect. Leonard came to my hotel, and—I’ll never forget it—there he was waiting in the lobby, this tiny man with a gray flannel shirt, gray trousers, with the fedora. He said, in that voice, “Let’s go to dinner.”

We went to dinner.

I don’t remember where we ate or what we ate. He took me somewhere, I don’t know. We talked and talked; everything around us disappeared. He told me about the dark times he’d gone through. I’d listened to so many of his songs, especially after my breakup, listened so closely to that deep, dark voice singing, “I’m your man,” and “There is a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in.” Now here he was in real life, meeting my pain with his own. It made me feel less alone. I knew he’d been through as much as me, maybe more.

Watch: Kate McKinnon Sings ‘Hallelujah’ for SNL Cold Open

He was close to 80 at the time, but he had an incredible vitality — even his descriptions of severe depression were completely alive. He told me how he’d found a Zen master in Los Angeles, an old, old man, close to 100, who’d never heard of Leonard Cohen or his music. Leonard went to the master’s monastery and stayed for a year; when he came back to the real world, his depression got even worse. So he returned to the monastery, and stayed for five years, waking every morning at four to meditate, washing his master’s room and making breakfast, lunch, and dinner for him. Every day. Five years.

“Marina,” he said, “one day I woke up, and the depression wasn’t there anymore.”

We talked for four hours, but it could have been 30 seconds—the time vanished. I was enchanted to hear about Leonard’s five isolated years of concentration and discipline and spirituality, away from his work, away from everything and everybody except for that very old man. I have gone on many retreats — sometimes for a week or two; once, in Tibet, for three months — but five years was far beyond anything I’d ever attempted. It was a renunciation I’m not sure I would be capable of.

Leonard told me that even though he had left the monastery, he still woke up every day at four in the morning to meditate. I looked at him with fresh understanding. This, I suddenly saw, was what gave him that incredible aliveness in the eyes, in the movement of his limbs. He was like a little bird — he just jumped. I had never encountered a presence quite like this.

Such aliveness doesn’t just go when the body goes. Leonard is gone, but his voice and his energy will be with us forever.

Abramović is an artist and the author of the memoir Walk Through Walls.

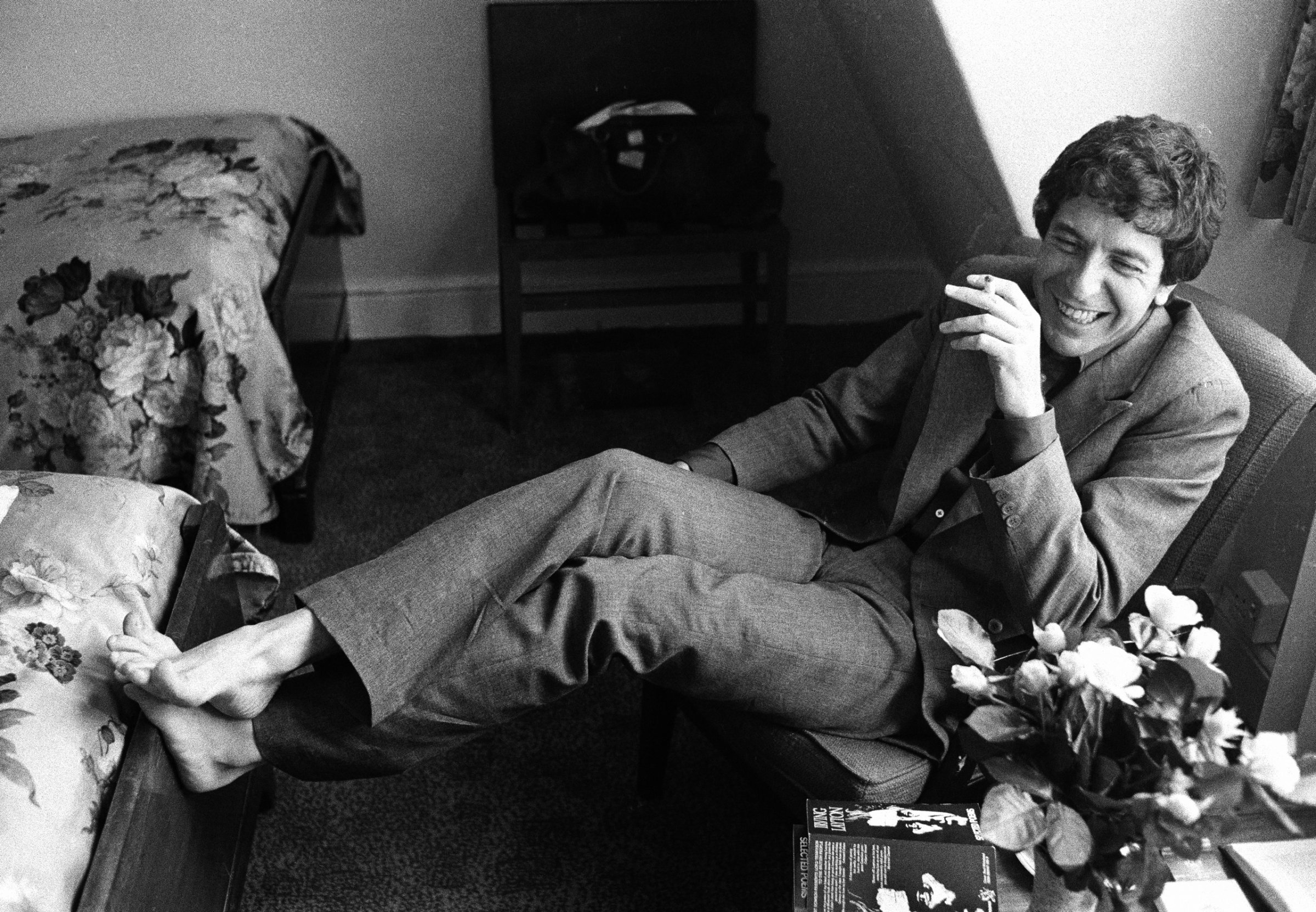

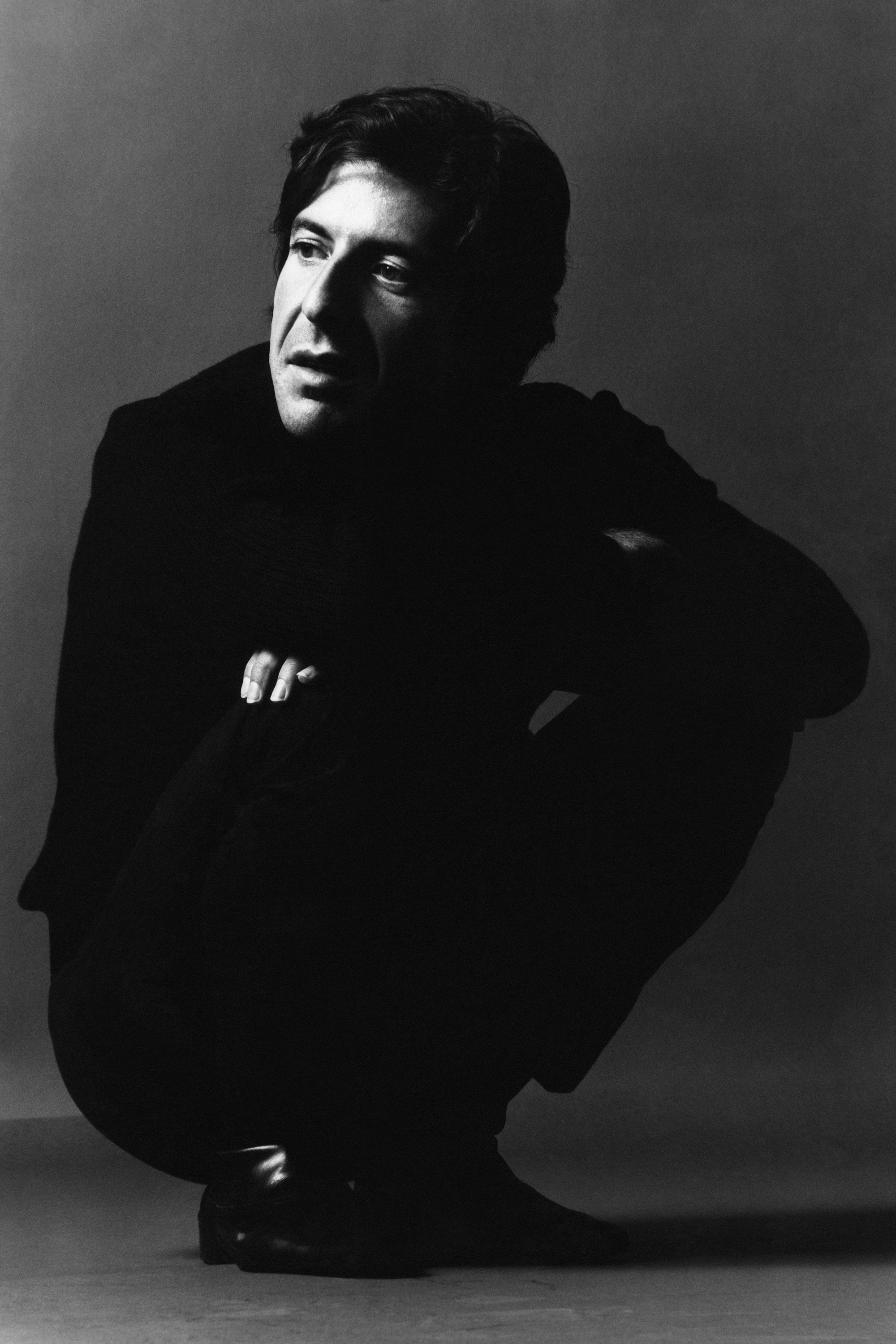

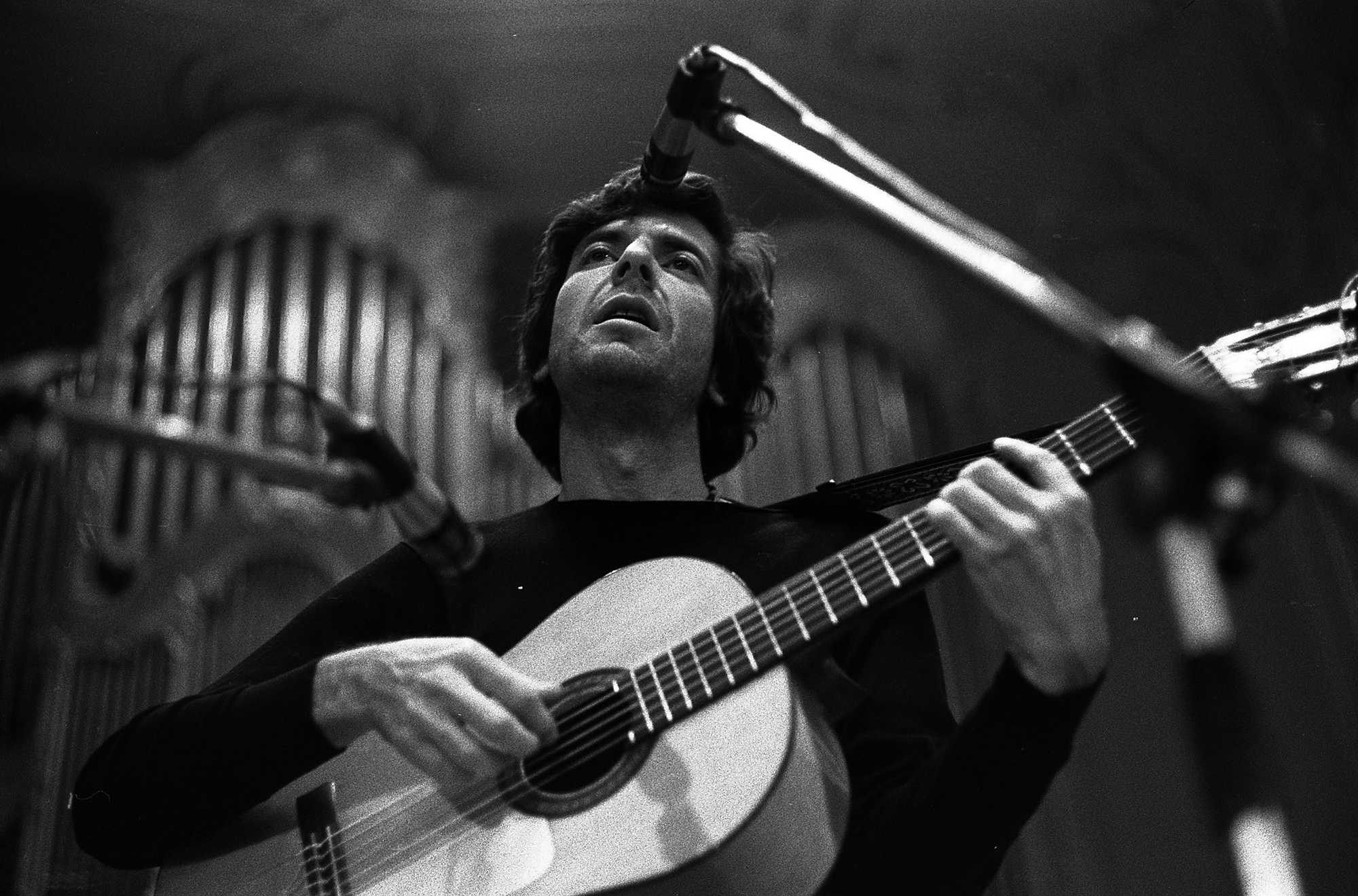

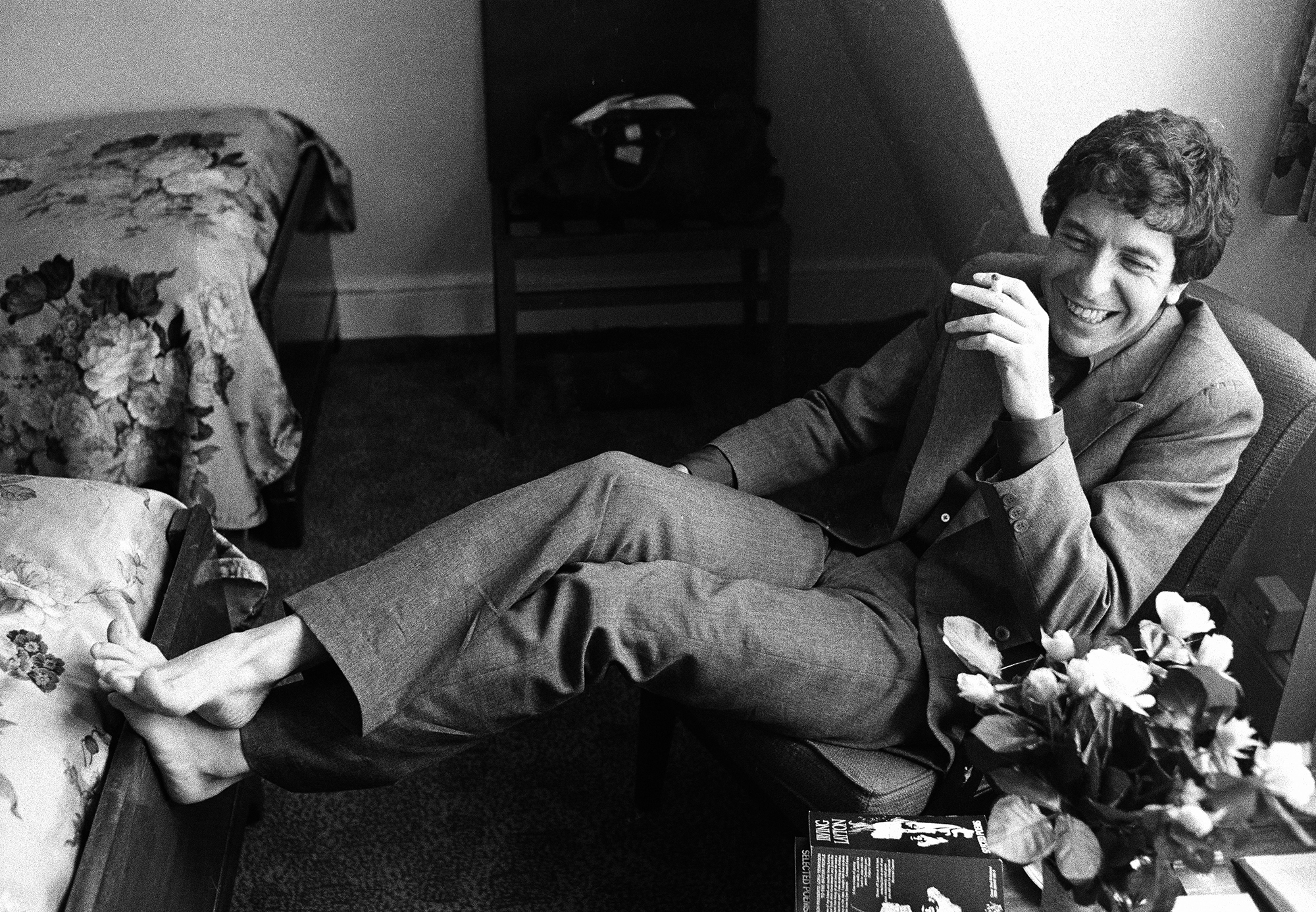

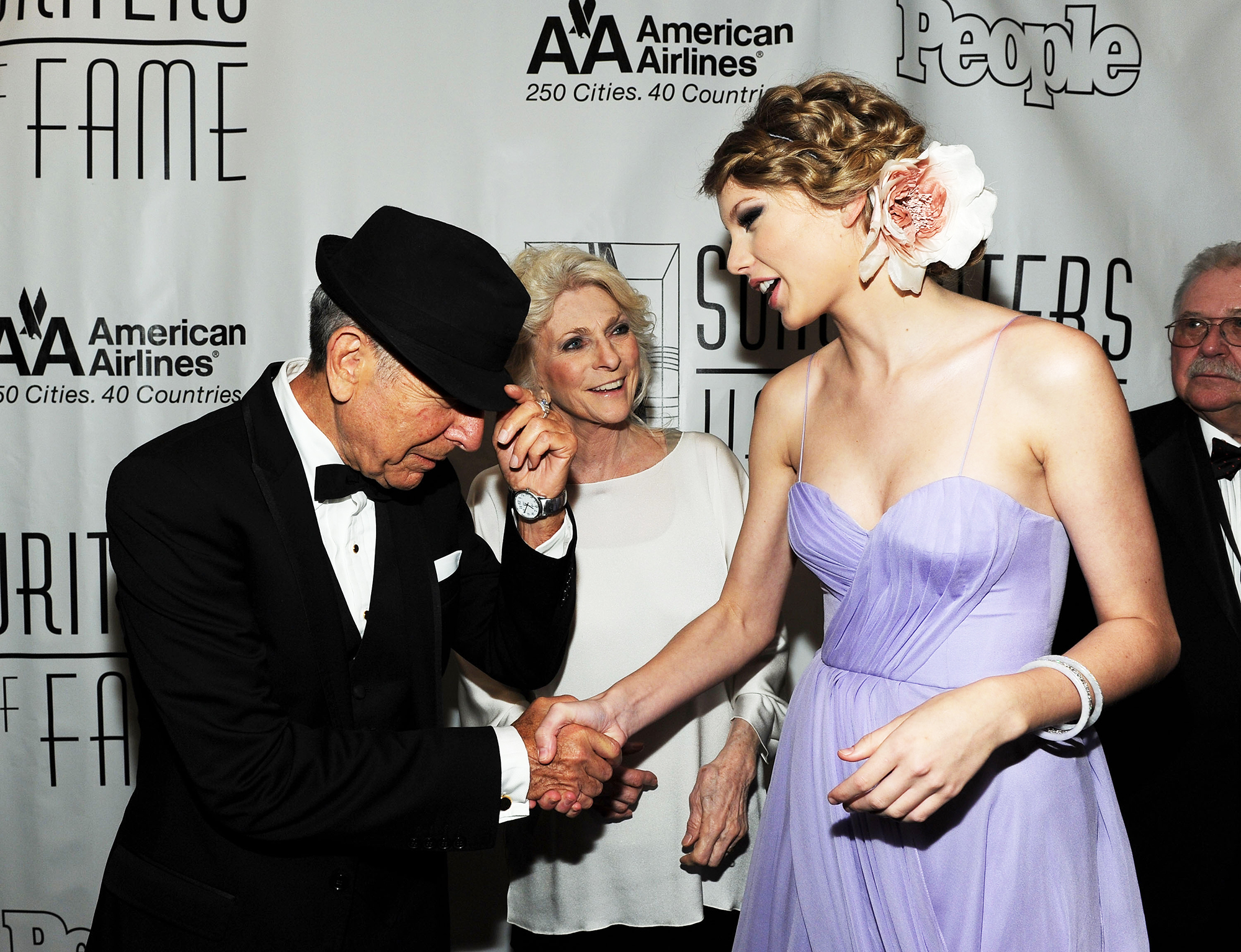

See Leonard Cohen’s Life in Pictures

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com