Michael Price is a counsel in the Liberty & National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law

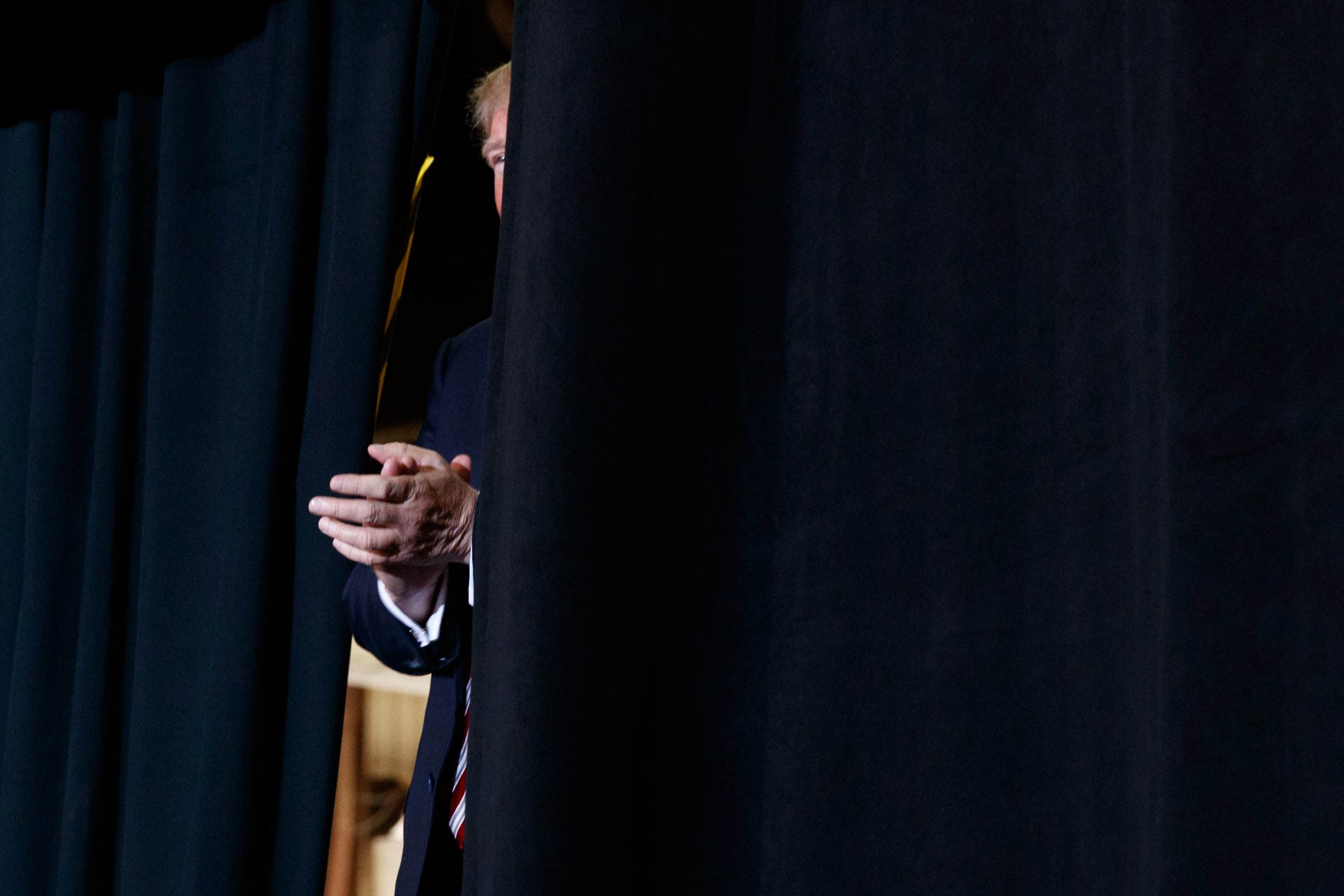

Donald Trump’s victory has struck fear into many Americans across the country, especially among the diverse communities he denigrated and among the individuals, activists and reporters he attacked from the podium. When he becomes president, he will wield the full power of that office, which means he will direct the most sophisticated surveillance apparatus the world has ever known. The argument against creating such a thing was that someone like Trump might get his hands on it and do all of the terrifying things he has promised to do.

Now that Trump has been elected, it is more important than ever to protect privacy rights and rein in government surveillance. Privacy is central to almost every major issue of our time, from immigration and reproductive rights to criminal justice, national security and the environment.

Consider the protests at Standing Rock, North Dakota, for example, during which more than 1.4 million Facebook users “checked in” at Standing Rock — from afar — to show their support and, perhaps, “overwhelm and confuse” law enforcement trying to use social media to track protesters. As a counter-surveillance tactic, it was a bit off the mark, but the virtual protest helps demonstrate how location information can be both sensitive and expressive.

Law enforcement can easily obtain information about protesters and activists of all stripes from the location data generated by their cell phones, regardless of social media activity. One option is to use a “Stingray” or similar device, about the size of a briefcase, which mimics a cell phone tower and causes all phones in the area to connect and reveal their presence. Police have reportedly used the technology to collect location information to identify Black Lives Matter protesters following the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.

Another option is to pull the same information from cell phone service providers that maintain cell towers in the area, often referred to as a “tower dump.” From that point, police can trace the location of any cell phone, in real time or for weeks or months in the past, by forcing cell phone companies to divulge communications records without a warrant. The records can be analyzed to identify the members, structure and participants in an organization or political movement. They can recognize the congregants at a church, mosque or synagogue. They could pinpoint protesters at Trump Tower or women visiting Planned Parenthood.

The problem is that there is no constitutional protection for phone location information — at least not yet. Based on a couple of cases from the 1970s, some courts have held that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in that data because it is logged and stored by service providers. They’re following an outdated legal rule called the “third-party doctrine,” which holds that people “assume the risk” that their data will be divulged to police if it is “voluntarily conveyed” to a third party.

The hitch is that’s how all cell phones work. But that’s not how privacy should work.

In three upcoming cases (Graham v. United States, Carpenter v. United States and United States v. Gilton), two of which are before the Supreme Court, the courts have an opportunity to abandon this approach in favor of stronger digital privacy rights. The Justices should recognize that people do not consent to location tracking by virtue of carrying a phone, something almost everyone does in today’s society. (The Brennan Center filed briefs in all three cases.)

Cell phone data is deeply private information because of its potential to reveal not just a moment in time, but all moments, a virtual time machine with enormous potential for abuse and stifling dissent. And as we enter a period of deep, urgent concern about government overreach, it is all the more important for the Court to recognize the realities of modern technology and find that the Fourth Amendment demands a warrant for law enforcement to access cell phone location records.

The privacy of location information is central to our democratic traditions. The Founding Fathers fought a revolution to protect privacy rights and freedom of speech, knowing full well that they are essential ingredients for a free and open society. As a nation, we must continue to fight for those rights—and everyone who relies on them. Neither changes in technology nor changes in leadership should be allowed to undermine these essential values.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com