As environmentally conscious Americans mark America Recycles Day on Tuesday, many may assume that recycling is a product of the environmental movement of the 1970s, the decade that saw the first Earth Day and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

But, though that time was an important turning point in the history of the idea, recycling in America goes back much further than that. In fact, some experts suggest that it worked better before the 1970s than it does today.

If creative reuse counts as recycling, people have been doing that for millennia—but early American recycling systems go back to the colonial era, when new materials were hard to come by. For example, metal was a scarce commodity at the time, says Carl Zimring, an environmental historian and professor at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, N.Y.—which is why Paul Revere would have had a scrap-metal yard. It’s likely that the horse he rode to announce that the British were coming was wearing horseshoes made out of what he collected, argues Zimring.

Into the 19th century, as peddlers traveled the countryside to sell manufactured goods, they also purchased recyclable materials from the households they visited, according to Susan Strasser, author of Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash. Rags were used to make paper, for example, and leftover beef bones could make fertilizer. Even well-t0-do Victorian-era American women who would buy a dress from Paris would send it back to the city to get alterations that incorporated whatever the new fashion trend was, whether it was new sleeves or collars, rather than buying a new dress. A 1919 survey in Chicago estimated there were more than 1,800 individual scrap-material dealers. (They didn’t all have good reputations, though: used materials were in such high demand that recycling carried a whiff of criminality, as it gave value to stolen goods.)

“The idea that you threw stuff out when it wore out is a 20th century idea” and a product of “a consumer culture that suggested that the new was better than the old,” says Strasser.

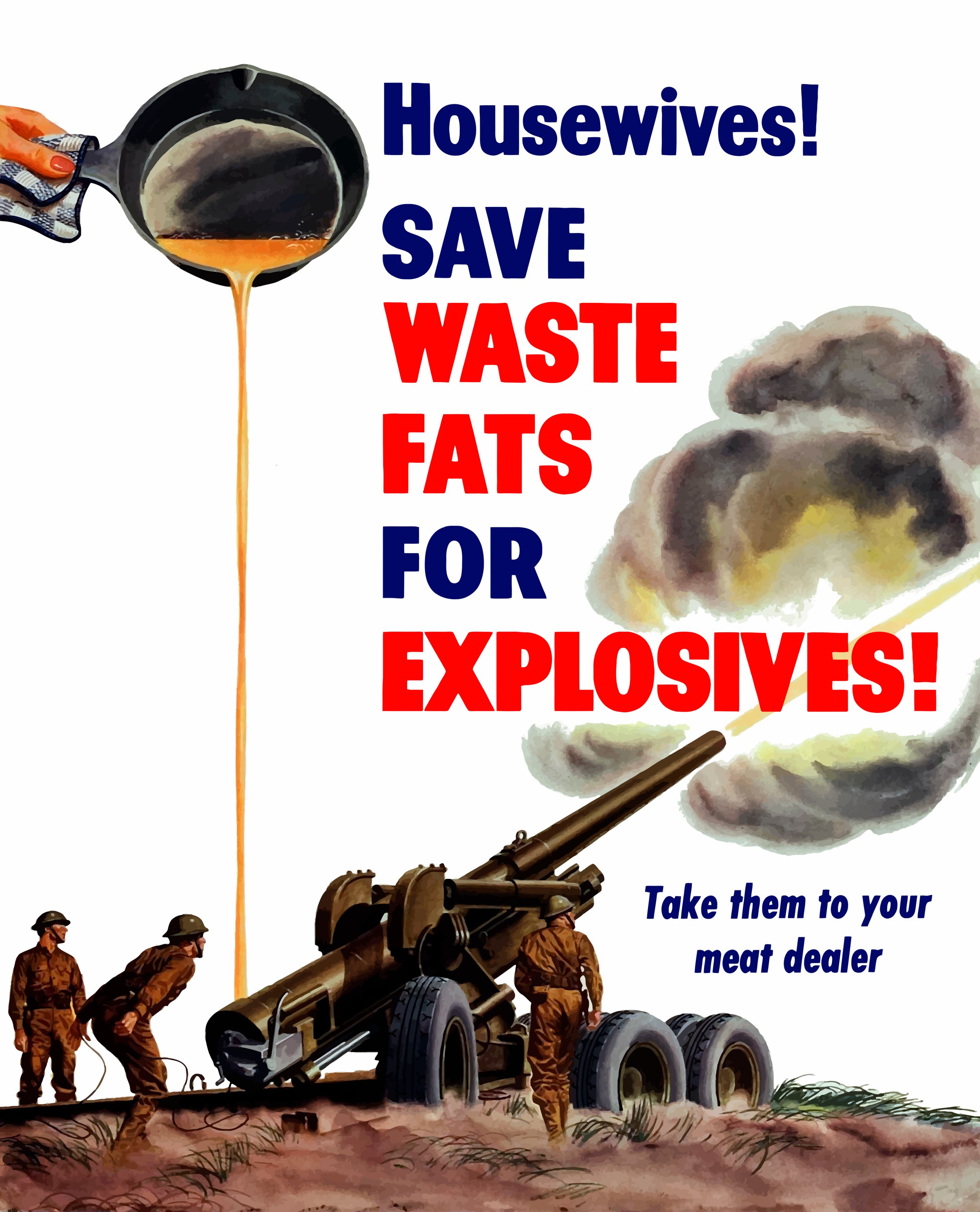

During the Great Depression, the need to reuse continued. Manufacturers marketed products by their dual-use potential. Families used biscuit containers as lunch boxes and flour sacks as fabric for clothing. And during World War II, Americans were famously encouraged to collect scrap metal, paper and even cooking waste—though many experts now say these items mostly piled up, unused, and that these campaigns were propaganda efforts to get schoolchildren involved in the war and gin up support.

What happened in the 1960s and ’70s wasn’t that recycling was invented, but that the reasons for it changed. Rather than recycle in order to get the most out of the materials, Americans began to recycle in order to deal with the massive amounts of waste produced during the second half of the 20th century.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

America Recycles Day is a national initiative of “Keep America Beautiful,” a coalition that was formed in the early 1950s by a group of public and corporate interests, including interested manufacturers like the American Can Company. As the American economy grew after World War II, so did consumers’ thirst for disposable cans, bottles and other single-use products, which piled up to the point that the organization called for the creation of collection programs in cities and for volunteers to pick up the trash in national parks. These first pick-up programs were publicly funded and started mostly in the Pacific Northwest and New England in the late 1960s and early 1970s. “People start pollution. People can stop it” was the tagline a famous PSA that featured an Italian-American actor as a crying Native-American man.

That ad can be seen as an important moment in the history of recycling, argues Bartow J. Elmore, environmental historian and author of Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism. The companies behind the campaign successfully framed waste as problem for consumers rather than one for the companies that manufactured the items being wasted, he says, and thus framed recycling as something that taxpayers should pay for. More than 10,000 communities had some sort of public recycling collection program in America by 1990, and curbside recycling started to take off around that time, too, according to some estimates.

“By pushing for curbside recycling, you’re mobilizing a nation to do a lot of labor for you, bring [trash] back to you at low cost and invest in a lot of infrastructure for you —infrastructure you don’t build and don’t own,” Elmore says.

In short, recycling stopped being a way for consumers to get more from their purchases and became something that cost people money or at least time.

The shift in the framing of recycling can also be seen in bottle-return deposits, says Elmore. In the first half of the 20th century, they were widespread and consumers saw getting their money back as a normal part of purchasing something in a bottle. “Putting a price on these thing would mean people would bring it back, and even early trade journals for soft drink industry at that time were constantly chastising bottlers who weren’t putting a price on the container,” he says. “Back in the early period, containers are doing 20 trips back and forth between bottler and consumer, largely because people wanted to get their deposit back.”

That system faded away over time, replaced by the idea that consumers should recycle for altruistic reasons, with the fate of the Earth in mind. As of April 2016, just 10 states plus Guam have a deposit-refund system for beverage containers. Elmore says it’s unsurprising that the widespread culture of automatically returning bottles faded too, once the economic incentives were gone.

Therefore, he argues that—even as environmentalism has become more mainstream—recycling advocacy efforts have failed in the last 25 years, given the recycling rate for items like bottled water may be around 30%.

“I think history shows us why it didn’t work,” he says. “Listen to industry itself in the early 20th century: If you do not put a price on packaging waste, then that stuff is going to be wasted, and it wont come back.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com