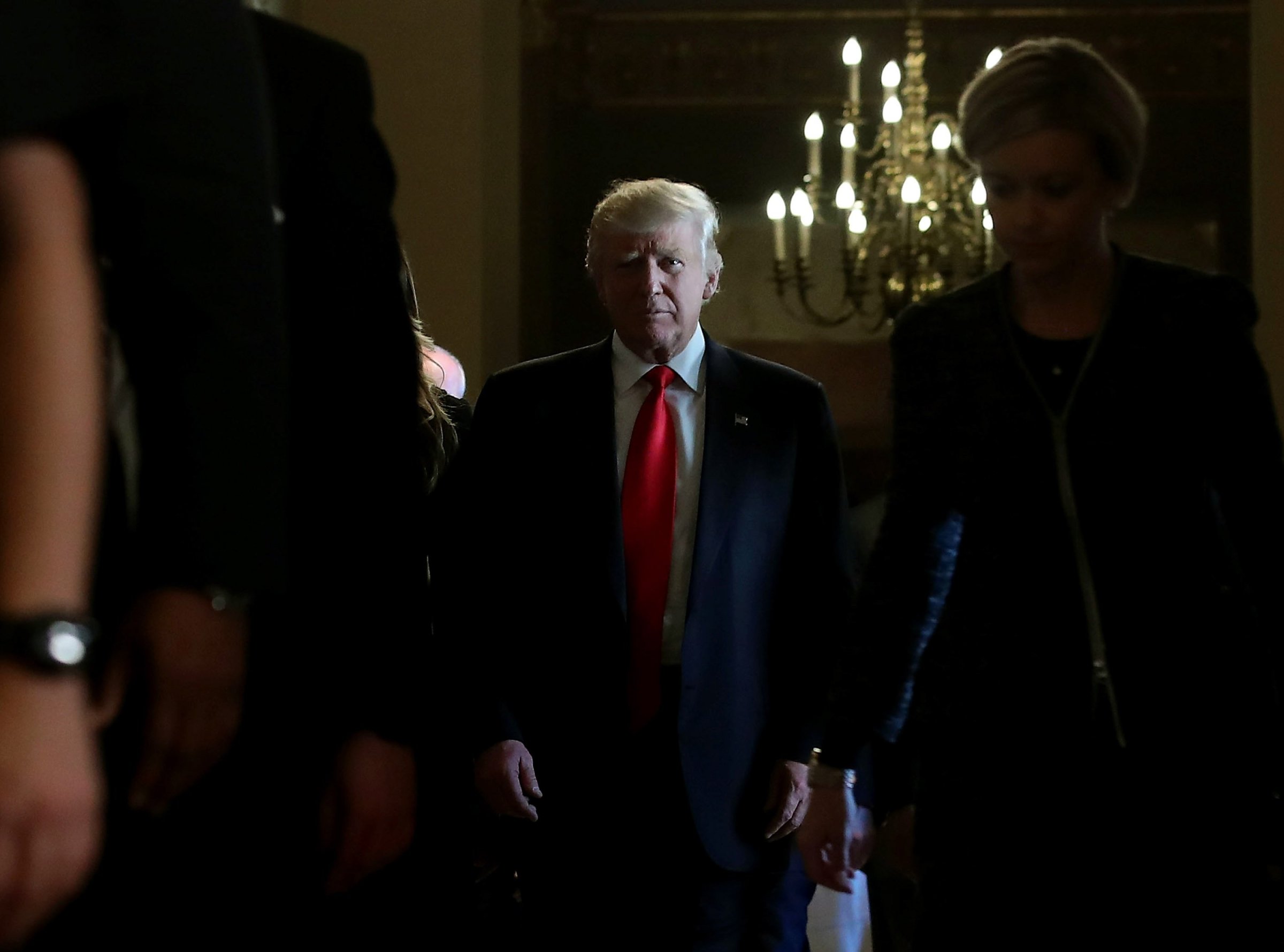

The United States woke up to what nearly everyone—save for Donald Trump’s most ardent supporters—considered impossible. Progressives across the country are in dismay, wondering how pollsters could have possibly gotten their numbers so wrong. But as Brexit showed the world this summer, 2016’s brand of populism continues to defy not only logic but our conceptions about the progression of modern politics as we know it.

We’re not out of the woods yet. Both France and Germany hold elections in 2017, with the former selecting a new prime minister and several parliamentary seats next spring. The latter is set to vote for local and parliamentary candidates next autumn. Both countries have grappled with their own racially charged politics for years; France’s National Front has fought for protectionist, anti-immigrant policies since 1972. A right-wing nationalist party, Alternative for Germany, has done the same since 2013. And as both countries vote during the nascent months of a Trump presidency, there’s every reason in the world to assume that their populist rhetoric will have a more sympathetic audience than ever.

Marine Le Pen, president of National Front, was one of the first politicians to congratulate Trump on his victory last night. When a Trump victory seemed all but unavoidable, Le Pen tweeted, “Congratulations to the new President of the US, Donald Trump, and the American people – free!” Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine’s father and founder of National Front, piled on by saying “Today, the United States, tomorrow, France. Bravo!” Florian Philippot, National Front vice-president, tweeted “Their world is collapsing. Ours is being built.”

As easy as it might be for Americans to either dismiss these messages as mere rhetoric from trans-Atlantic political bedfellows, there’s reason to believe that National Front might just deliver on this promise. The party did shockingly well during France’s 2014 municipal elections, winning mayoralties in 12 French cities. The party did well during 2014 European Parliament elections as well, winning 24 out of the country’s 74 seats. In 2015, National Front outperformed expectations, placing first in in six of the country’s 13 electoral regions.

And on the coattails of Brexit and Trump victories, Le Pen’s chances of winning the French presidency this upcoming spring are stronger than ever. The self-proclaimed “Madame Frexit” saw her popularity surge after the U.K. referendum, promising that she would push for France to leave the E.U. as well if elected. An October poll by Odoxa suggested that 74% of French conservatives support National Front’s push for a larger voice in the nation’s politics. By contrast, only 53% of French conservatives polled in the same survey said they felt the same way about Alain Juppé, a conservative politician who is still considered by political insiders to be the favorite in France’s presidential election next year. Most surprising of all was the poll’s result that 50% of those surveyed—both liberal and conservative—considered Le Pen to be an important political figure that should have a broader say in the future of French politics. With Trump’s victory in the U.S., Le Pen is all but guaranteed to have an outsized influence on French politics, even if she fails to win the presidency.

Although Alternative for Germany might be a younger presence than National Front, the party’s rise to prominence (in addition to nationalist populism at large) is a troubling development for the country’s otherwise progressive social politics. What began as a small, fringe party whose influence was relegated to municipal races has since gained popularity across Germany—particularly with former members of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union party who became disenfranchised by her pro-EU, pro-refugee policies that stood at odds with the German electorate. One of the party’s biggest draws is its anti-Muslim, anti-immigration policies, which is to say nothing of its roots as an anti-EU organization. The rise of Alternative for Germany couldn’t come at a worse time for the CDU, as Merkel’s popularity hit a five-year low last month. The CDU still leads among polled voters, but Alternative for Germany sits in third place among likely voters if the election were to happen today. So even if the right-wing, nationalist party does not have a shot of taking over control of the German Bundestag, its presence will be felt throughout the country’s politics for years to come.

The anti-immigrant, isolationist phenomenon that first appeared by way of the surprise Brexit result was merely the end of the beginning. Few aside from former U.K. Independence Party (UKIP) leader and current E.U. parliamentarian Nigel Farage could have anticipated that the United States would find a way to one-up its British cousins by voting for Trump. But now that President Trump is coming, we must look at this election in the broader context of Western populism—a trend that shows no sign of true direction but also shows no signs of weakening anytime soon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com