“Poverty” is a loaded word, especially in the U.S., and few know the ugly reality of its use better than artist Brenda Ann Kenneally. At its core, her work is a study of life and opportunity under straightened circumstances in the upstate New York city of Troy. But instead of categorizing her subjects as “poor” or “unemployed”, she promotes a deeper understanding, with all its messy complexity; the ultimate antidote to populist “fast” media.

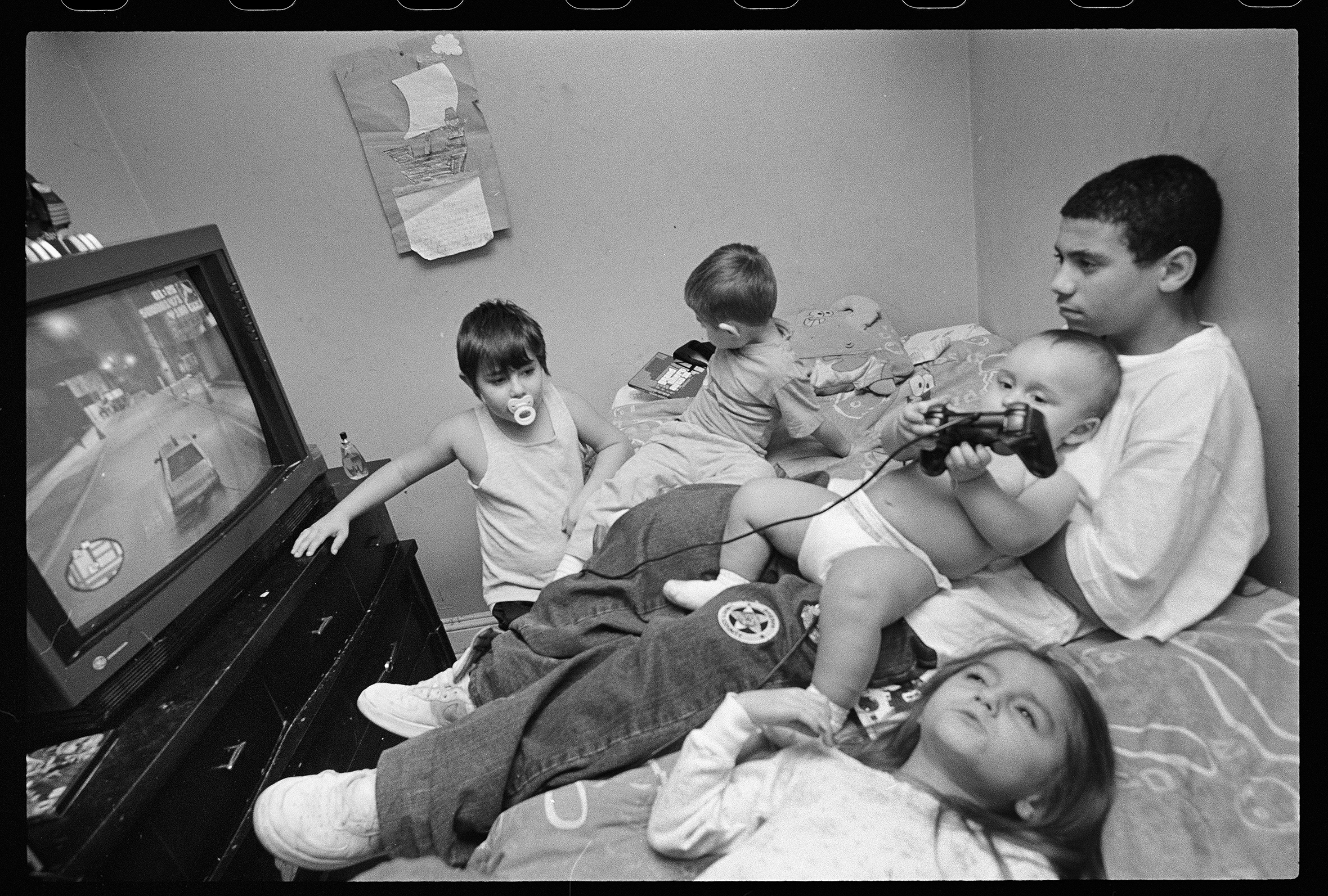

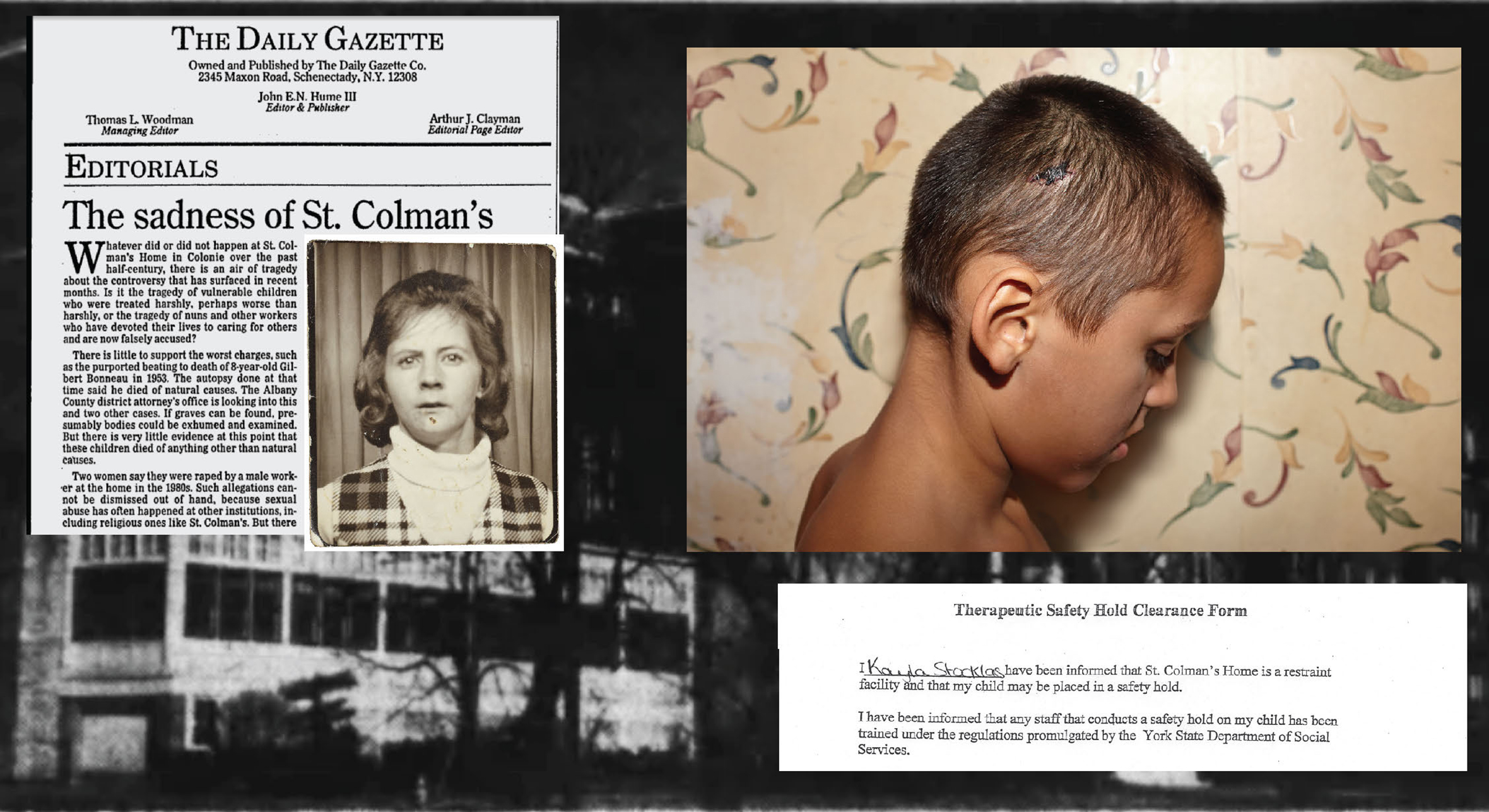

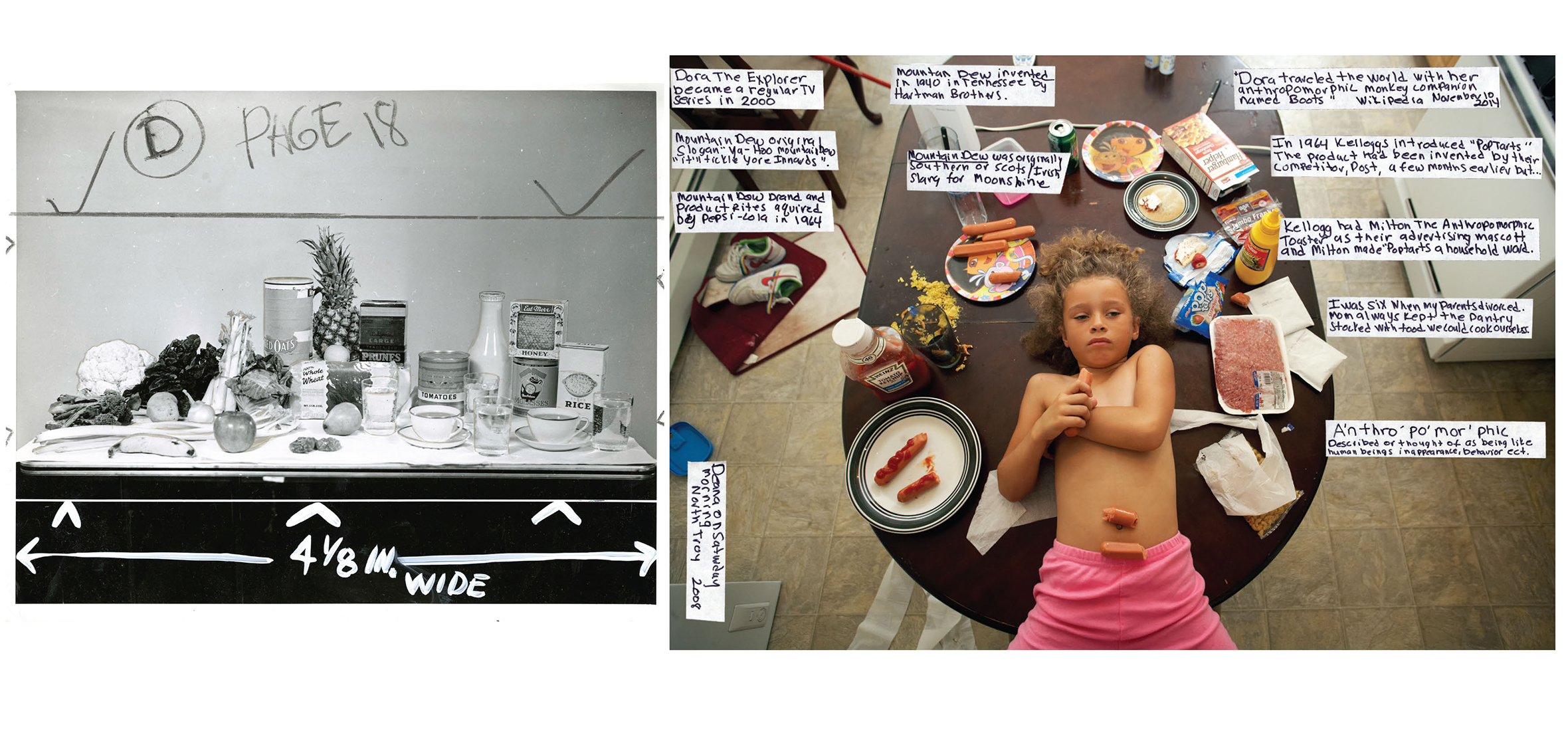

Context has always been central to Kenneally’s projects. She’s there for the births, the deaths, the incarcerations and birthday celebrations, all carefully documented through photography and collected ephemera. Now, the in-depth work, which spans 12 years, has culminated in the launch of North Troy People’s Museum, which opened last month. The digital-folk artist hopes the museum will open a complex discussion without diminishing the participation of the people she worked with. “I need to protect the people who allow me to document their lives,” says Kenneally. “The very lives that teach so much understanding but are also a touchstone for hate.”

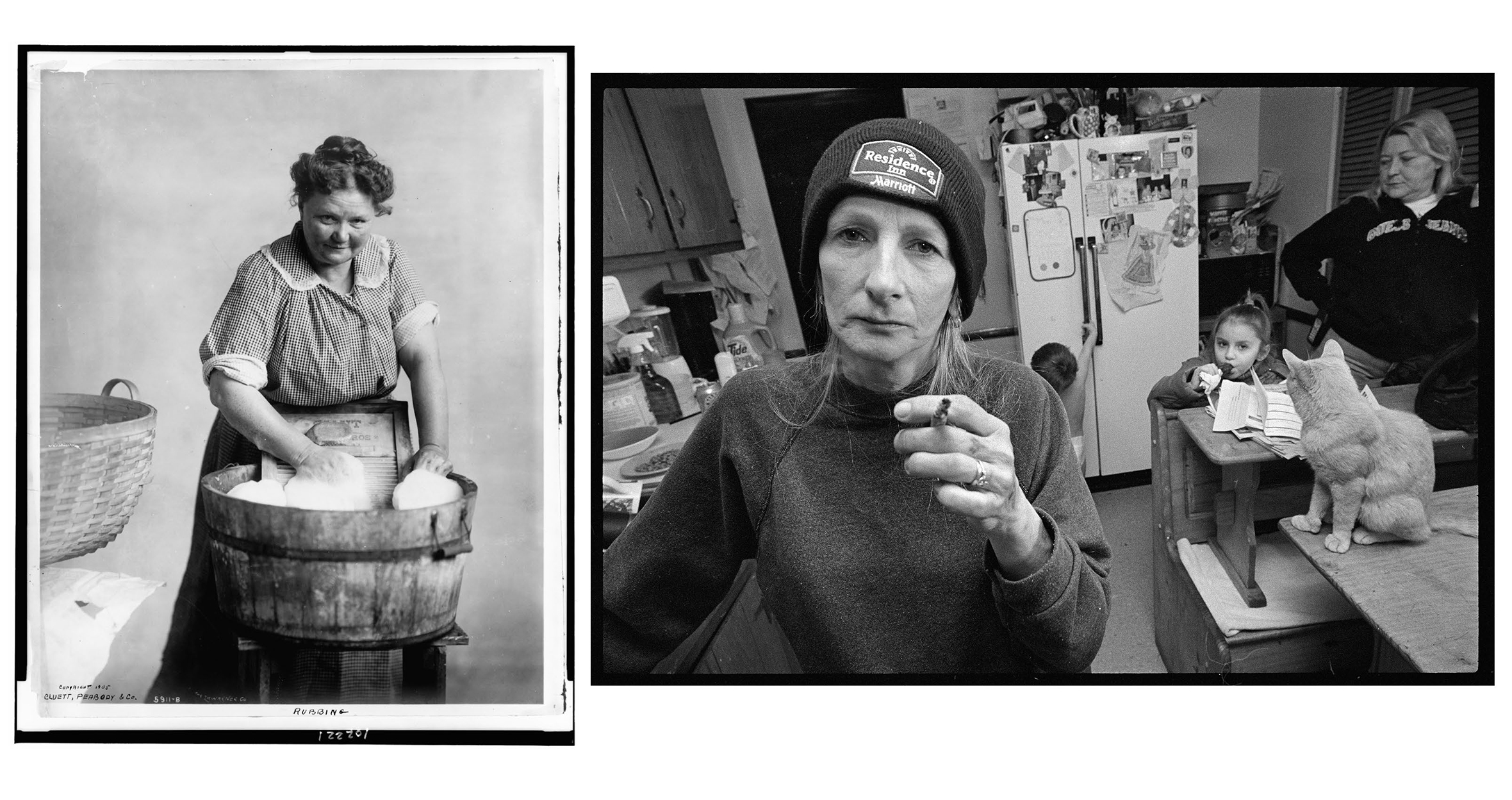

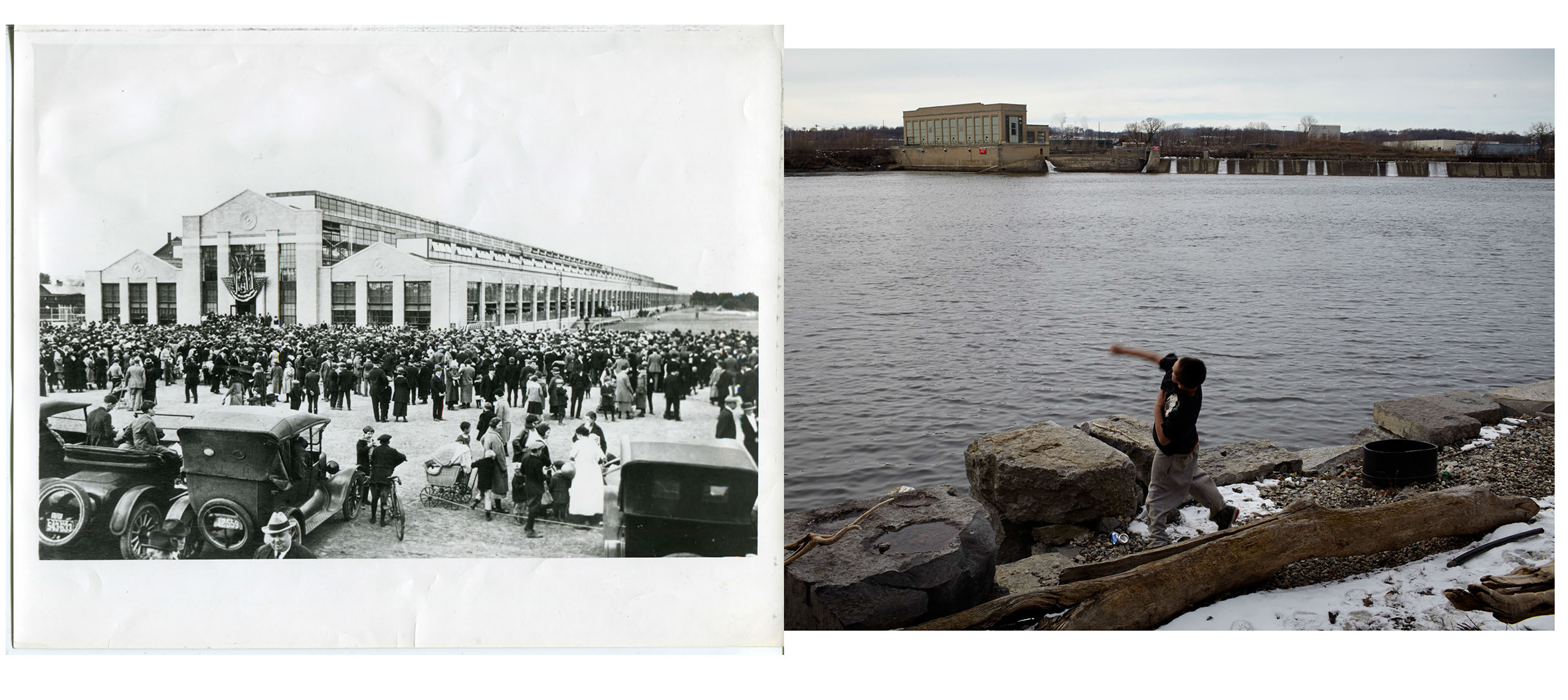

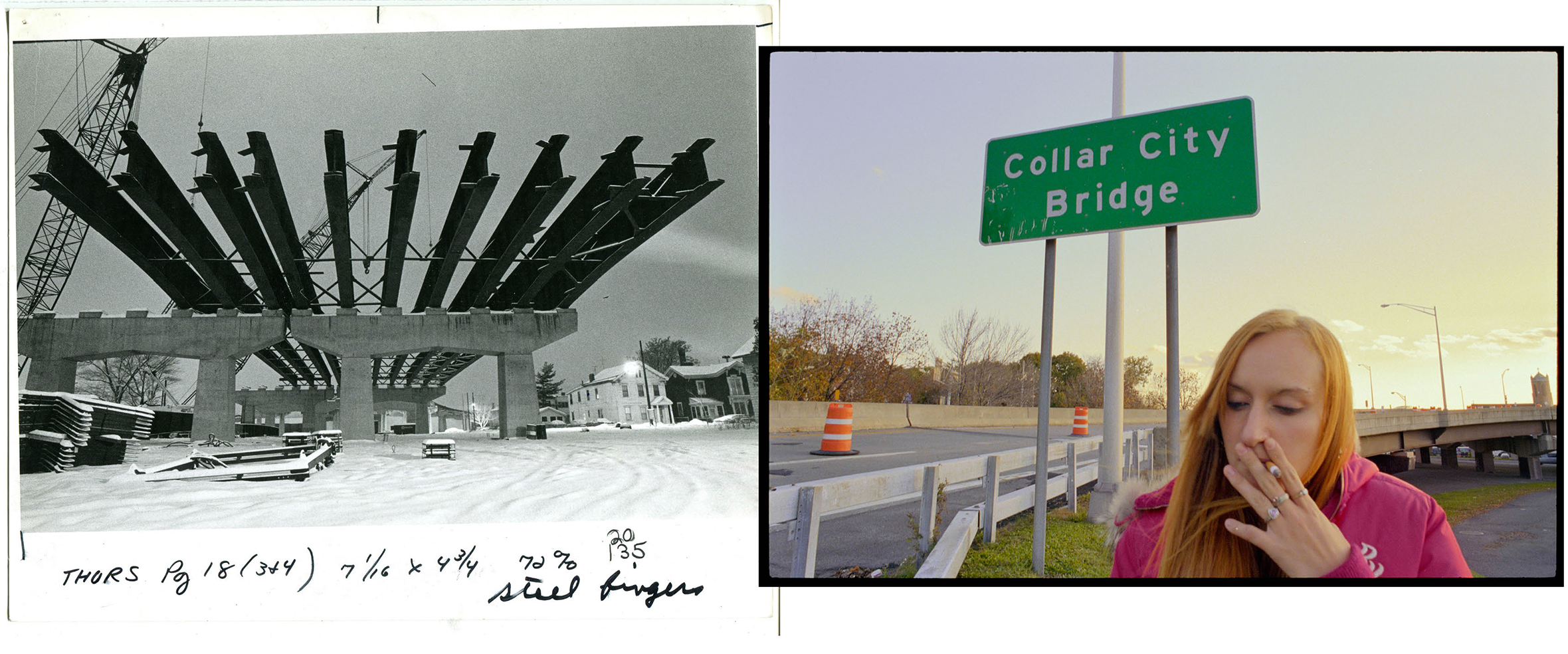

The museum is housed in the former home of one of the families Kenneally chronicled. That family was forced out after a series of bank and real estate missteps. Now it is an homage to these people’s history – along with many others who Kenneally has closely followed over the last decade. Running through the ground floor is a mural that offers a timeline from the Paleo Indians to the present, scrapbooks with historical ephemera such as jail letters, probation reports and maternity tests are also on display – and of course blown up prints of her arresting photographs. The People’s Museum cleverly weaves the historical with the contemporary, giving context to the rise and fall of Troy’s social and domestic landscape. By putting past and present side-by-side, the grim reality of generational poverty is put in perspective, says Kenneally.

The photographer grew up in nearby Albany and her childhood was fraught with “a lot of bad stuff,” she says. Her family had little money and she became dependent on drugs and alchohol from a young age. But she broke the cycle of “damaged child becomes damaged adult” and left her toxic homelife aged 17 to study in Miami. Her photography has in part, been a chance to “re-do” her past, this time with more control. “Through understanding these kids more and more I understood what had happened in my own life,” says Kenneally.

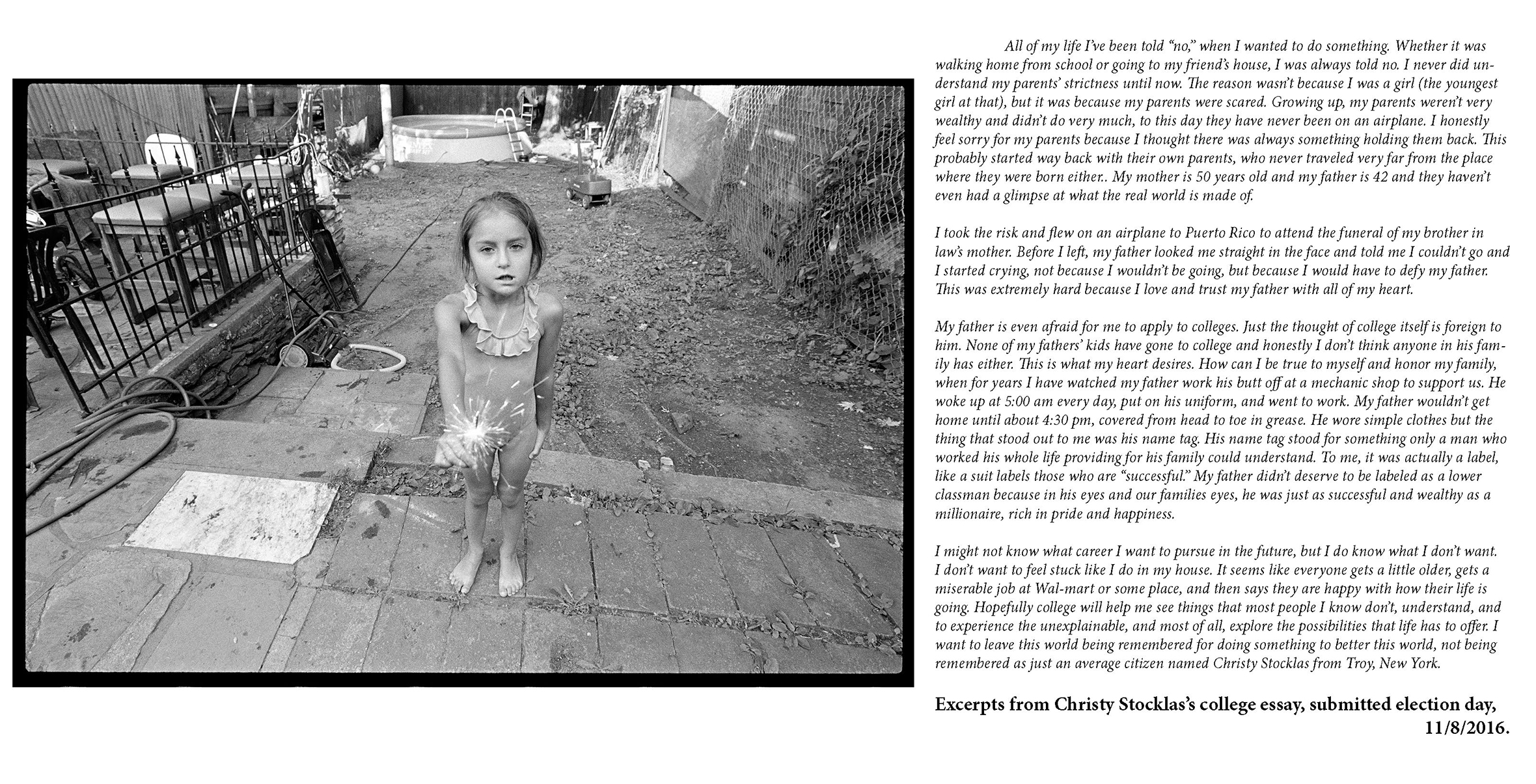

Her layered documentary project Upstate Girls: Unraveling Collar City drives the exhibition’s content. It’s intensely intimate – “which some might find uncomfortable” – and hyper-local. But its “realness” reaches across the vernacular. If Troy was once the prototype for the industrialization of America, in 2016, it could be said to represent the fall of these once thriving communities. Scant employment opportunities and high incarceration rates plague the city and, as with many blue-collar neighborhoods, the American Dream is a faltering myth. In this year’s presidential election, Rensselaer County – of which Troy is the capital – went to Trump with a 3% margin, perhaps a rejection of the status quo that has done little for the working class over the last decade.

The museum is also in response to a million dollar temporary art installation – a think piece from the Bloomberg-funded Breathing Lights Project – where more than 50 abandoned buildings in the neighborhood are lit up with a “soft, amber glow”. Though channeling a positive message in theory, Kenneally feels it only opens up a “one-dimensional conversation”. The irony of the vast expense of this project juxtaposed with neighboring homes where people can’t afford new socks, isn’t lost on her either. “I respect what they’re doing,” says Kenneally. “But if I were critiquing it and I was on that committee, I would say: ‘And then what?’”

Kenneally hopes the People’s Museum will give the community more creative agency and be an antidote to the “art-washing” that’s sweeping economically depressed areas across America. As Noam Chomsky said, at its core, class is simply defined by those who make the rules and those who follow them. Creative class is no different. As well as the museum, Kenneally has set up an artist’s residency for marginalized youths aged 18-21 from upstate New York. The residency, called A Little Creative Class, breaks down the cultural barriers that Kenneally’s subjects have all faced and which she was able to overcome. “I started the residency as a way to put into practice all I have learned from my years reporting in Troy,” she says.

Kenneally’s work began nearly 13 years ago but until “real legislative change” has been enacted she says it won’t be complete. For her, the formula is simple: “I feel like the people at the top need to make real changes and the people that have too much money need to give some up. People show love by giving money – to institutions or to each other – and they show hate by withholding it.” Despite her tireless work, she feels she is yet to shift the dialogue around depressed communities, in part because America is “based on the idea that we are a classless society.” And until the semiotics are confronted head on, poverty will perpetuate.

Brenda Ann Kenneally is a digital-folk artist based in New York. Her Upstate Girls project can be viewed on her website. North Troy People’s Museum is open to the public until Jan. 1, 2017. Visits are by appointment only. A Little Creative Class will be open for residencies from fall 2017.

Paul Moakley, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s deputy director of photography and visual enterprise. Follow him on Twitter here.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com