The good news for President-elect Donald Trump is that the U.S. military is, formally, an apolitical institution that takes its orders from the commander-in-chief, whoever he might be. Defense Secretary Ash Carter issued a memo to everyone in the U.S. military Wednesday morning, saying the election happened “freely and peacefully” because of their work. “I am committed to overseeing the orderly transition to the next commander-in chief,” he said. “I know I can count on you to execute all your duties with the excellence our citizens know they can expect.”

The bad news for the newly-elected President is that the military has informal ways of subverting those same orders, especially if it and Congress enter a tacit alliance to derail them.

Trump has called for boosting defense spending by about $60 billion a year—a 10% hike—and an end to the lengthy, inconclusive wars that the U.S. has waged in Afghanistan and Iraq. He has said he wants to “bomb the shit” out of ISIS as part of his war plan because “I know more about ISIS than the generals do, believe me.”

That’s not a good way to launch a productive working relationship with the generals and admirals who command the nation’s 1.4 million soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines. Look for Trump in the coming days to scale back such rhetoric, just as he did in his acceptance speech early Wednesday when he spoke graciously of Hillary Clinton, who he had vilified for months. Such temperance will be required if U.S. national-security policy is to remain coherent.

“Trump’s very first steps as President-elect were about as good as could be hoped for,” says Peter Feaver, an expert on civil-military relations at Duke University, who served on the White House’s National Security Council during the Clinton Administration. “He promised to be a President of all Americans, and pointedly avoided mentioning the divisive issues that were prominent in the campaign.”

“The senior military will do what they’re told, and many will welcome the change,” says Merrill McPeak, a retired Air Force general. “Let’s at least hope it will be good to have an out-of-the box thinker” not burdened by policies that have led to 15 years of un-won wars at a cost of nearly 7,000 lives and an estimated eventual cost of $6 trillion. David Barno, a retired Army three-star who led U.S. troops in Afghanistan in 2003-05, says the President-elect also needs to jettison “the inflammatory campaign rhetoric that sometimes cavalierly suggested a need to replace today’s generals and admirals with ones of Trump’s choosing.”

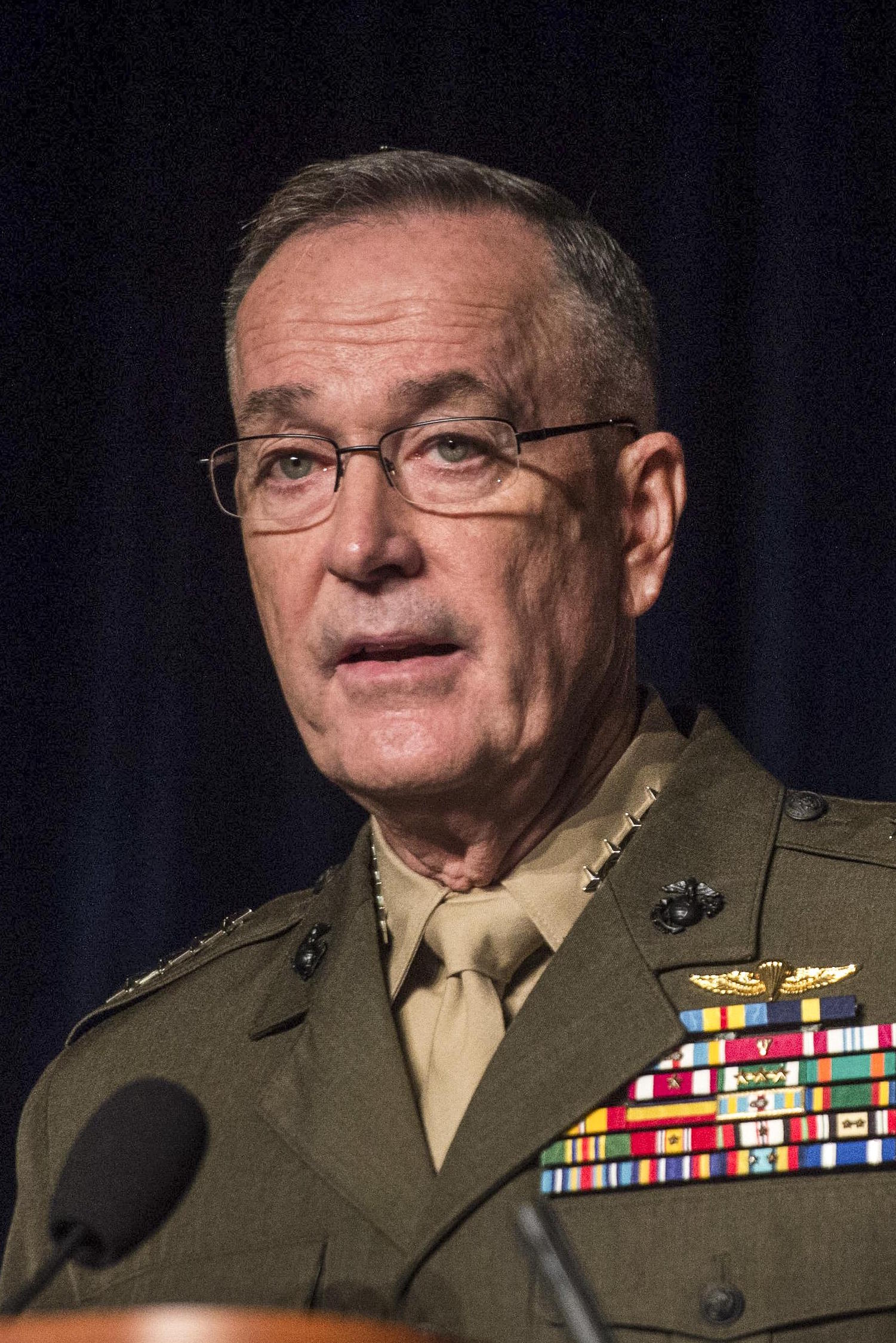

With no military experience, Trump’s key tutor will be Marine General Joe Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Military officers, unlike nearly all civilian political appointees, don’t lose their jobs when a new Administration takes office. By law, the chairman is the key military adviser to the president, and Dunford wins high marks inside the Pentagon for his military smarts and political skills. “As of January 20, we will have a commander-in-chief who is quite literally ignorant of basic U.S. national-security policy,” says Andrew Bacevich, a retired Army colonel and military scholar. “It will be incumbent upon senior military leaders, above all the Joint Chiefs’ chairman, to contribute to his education, an urgent and sensitive task. It remains to be seen whether they will rise to the occasion.”

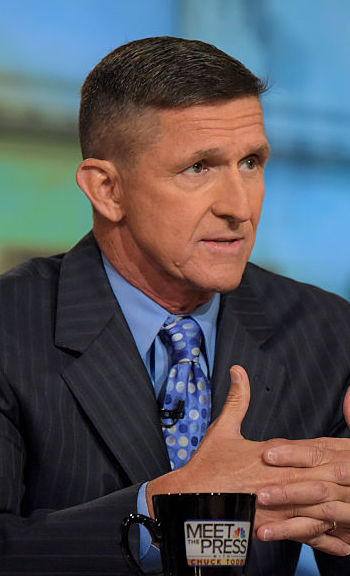

Given his dearth of experience, Trump also will have to select national-security leaders that can reassure Americans at home and leaders abroad that there is a steady hand on the tiller. “The personal qualities of those selected for political appointments in the defense establishment can be more important than pronouncements in party platforms or campaign rhetoric,” says Charles Dunlap, a retired two-star Air Force general. “I would also hope that retired flag officers return to the military’s apolitical tradition, as opposed to the overt partisanship we saw from some during the campaign.” That could rule out Mike Flynn, the outspoken retired Army lieutenant general, who as recently as Saturday criticized Clinton for what he called her “unbelievable active criminal behavior.” His name has been floated as a possible defense secretary, director of national intelligence or White House chief of staff in a Trump White House.

While a President has more leeway overseas—including wars—than he does at home, Trump won’t be able to achieve major national-security changes unilaterally. Only the Senate can ratify treaties, and only Congress can increase defense spending. While Republicans will be the majority in both houses in the new Congress to be seated in January, it’s likely to include as many deficit hawks as defense hawks.

The military rank-and-file supported Trump, according to unscientific polls conducted during the campaign. Many come from rural parts of the country that helped Trump win, military officers said Wednesday. Some of Trump’s claims—that he knows more about battling ISIS than the generals he soon will command, for example—was “political theater” that some didn’t take seriously.

“Donald Trump has laid out a comprehensive, detailed, and forward-looking vision for the future of the American military,” ex-Air Force secretary Mike Wynne noted recently. “It is predicated on peace through strength and a sober appraisal of U.S. national interests.” Trump wants to boost the Army to about 540,000 soldiers, or 90,000 more than under current plans. He wants a 350-ship Navy and a 1,200-fighter Air Force, 10% increases over existing plans. The Marines would grow by 30%, to 240,000, under Trump’s proposal.

But there seems to be a mismatch between how robustly Trump wants to bolster the Pentagon and what he wants it to do overseas. He has expressed a wariness to get involved in ill-defined conflicts. He also has shown a reluctance to let other nations—particularly those in the NATO alliance—count on continued U.S. military support if they don’t spend more on their own militaries. He’s basically calling for a wartime military with a peacetime mission. And while Trump’s “America first” policy may make for a populist sound bite, it could lead to an isolationist nation where desiccated alliances—a major force multiplier for the U.S.-championed spread of democracy and free trade since World War II—could increase Chinese and Russian influence around the world.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com