This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Secrecy has been a prominent and persistent theme throughout this unusual election cycle. From Donald Trump’s undisclosed tax returns to Hillary Clinton’s secret emails, each presidential candidate has repeatedly accused the other of improperly withholding information from the public. When WikiLeaks released a transcript of a previously unpublished speech Clinton delivered behind closed doors, in which she reportedly said that politicians need to have separate public and private positions, the revelation intensified suspicion of what might be happening outside the public’s view. The secrets, the way they’ve been exposed, and above all, the suspicion that Clinton especially holds contradictory public and private opinions are enduring sources of anxiety among voters as Election Day approaches. The whole situation can seem unprecedentedly bizarre and downright alarming.

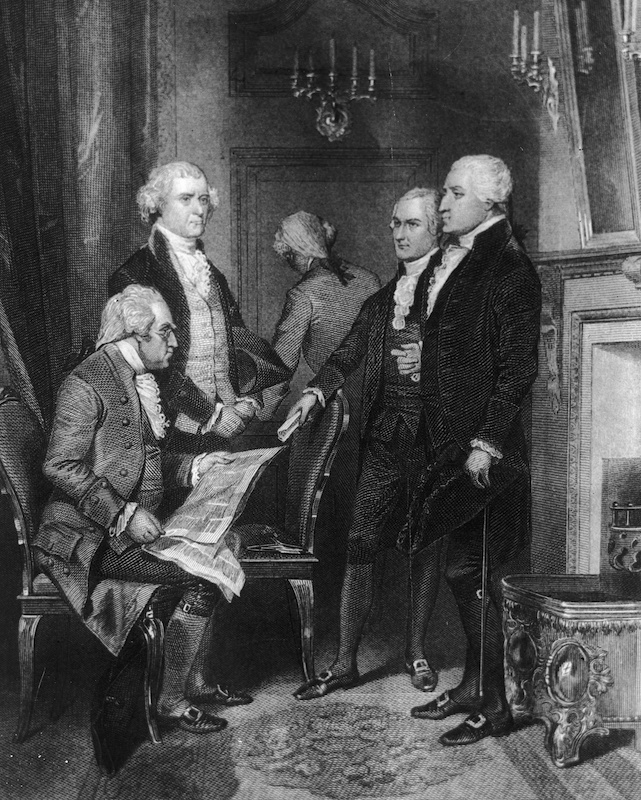

But the questions of what our elected officials should be required to disclose to the public and of when, if ever, keeping secrets is justified actually go back to our nation’s founding. Though it is frequently forgotten, the Federal Convention that met in Philadelphia over the summer of 1787 to draft the Constitution worked in secret. Writing to Thomas Jefferson, who was in Paris at the time, James Madison explained that members of the convention were prohibited from divulging anything that happened inside as a precaution to facilitate “unbiased discussion” among the delegates and to prevent errors or misconceptions from circulating among the public. For his part, Jefferson didn’t agree that the embargo was a good idea, writing to John Adams later that summer that he was sorry the delegates had decided on so “abominable a precedent.” Nothing could justify such secrecy, he wrote, other than “the innocence of their intentions, and ignorance of the value of public discussions.”

Throughout the ratification debates, those who opposed the new federal framework frequently pointed to the fact that the framers met behind closed doors as cause for concern. If the people were not allowed to see how delegates had hashed out disagreements and come to compromises, how could they trust that it was not a conspiracy or that the delegates had not just disregarded their constituents’ interests? Moreover, in a number of state ratifying conventions, opponents of the new framework raised concerns that the Constitution gave future elected officials too much leeway in determining when they could keep congressional proceedings and records of government expenditures from the public.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

During the early years of the Republic, the question of what officials were required to publicly disclose and when it was acceptable to keep secrets continued to be highly contested. Members of George Washington’s administration met mostly in private and carefully weighed when to publicly divulge information they considered sensitive. Representatives and Senators, too, made daily decisions about what to keep secret versus what to publicize, cautiously distinguishing in their letters between the information they intended to have forwarded for publication in local newspapers and the opinions they intended to keep private. Deliberating or opining on issues outside the public’s view did not go un-critiqued at the time. Some, like Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay, lamented that backroom dealings and secret negotiations were corrupting the Republic, which they believed depended upon transparent government.

As in the 1790s, the concern today is not just that the candidates kept secrets, but that this suggests they may have divergent public and private beliefs. In the second debate, Clinton attempted to contextualize her statement that politicians must have public and private positions by saying she was referring to President Abraham Lincoln’s belief in the utility of maintaining separate spheres. According to the transcript published by WikiLeaks, Clinton compared politics to sausage being made, noting that if everyone watched all of the discussions and deals, they would end up nervous. Essentially, she seemed to suggest that separating public from private discussion can be beneficial to the political process. Trump, who has himself been insisting on a separation between his private and his public statements about women (after the comments made on a bus eleven years ago), attacked Clinton in the debate for standing by what she had said. Voters remain uneasy with the notion that there can or should be a difference between a candidate’s public and private statements.

But Clinton’s assertion predates even Lincoln, as does unease with her suggestion that limiting transparency can be a legitimate part of representative politics. At times George Washington referred to a curtain between government and the public, which he seemed to have at least sometimes considered useful. Explaining in 1789 why he had temporarily cut off correspondence with a friend who didn’t share his political persuasion, Washington lamented in a letter to him that he had “found from disagreeable experience, that almost all the sentiments extracted from me in answer to private letters or communicated orally, by some means or another, found their way into the public gazettes.” This undesirable outcome was hard for Washington to avoid, even in an age long before email, Twitter, and recording devices. He decided it was better to halt communication in that case rather than risk leaks of his private reflections.

Our worry about public officials keeping secrets is far from new. Though history doesn’t offer an answer to the question of whether secrecy is acceptable, it does make the stakes of this concern clear. The unease is not just about the character of Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump; it strikes to the heart of a perennial puzzle in representative democracy, dating back to its founding.

Katlyn Marie Carter is a PhD candidate in History at Princeton University. She is completing a dissertation about representative politics and state secrecy during the American and French Revolutions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com