Facts don’t matter, only our reactions to them. Different people see different truths. There are no right or wrong answers.

The Rorschach test is a perfect metaphor for a polarized, relativist world. And this Election Day—the new high point, or low point, of such a world—happens to fall on the birthday of the test’s creator, Hermann Rorschach, born in Zurich on November 8, 1884.

The real Rorschach test doesn’t work that way, though. The blots aren’t arbitrary, but carefully designed to call forth specific aspects of how we approach the world. Far from being in the dustbin of medical history, the test remains a powerful tool still widely used in clinics and courtrooms today. In other words, even the Rorschach test is not a Rorschach test, not something that means whatever you want it to mean.

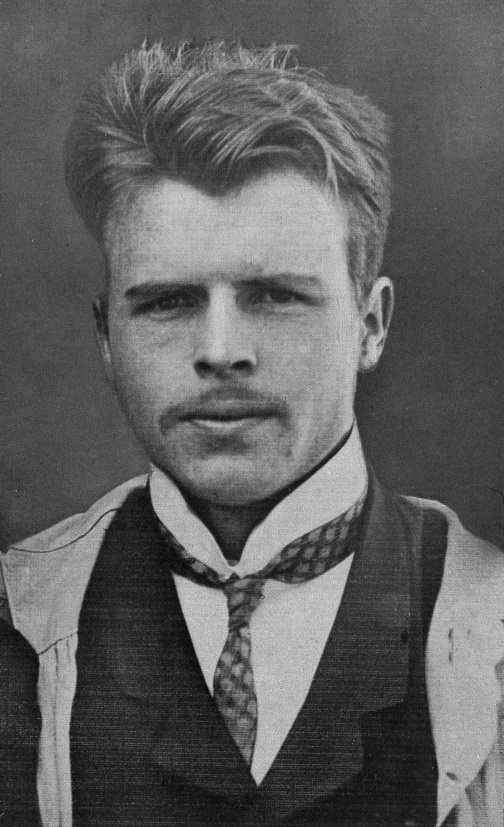

Hermann Rorschach was a Swiss psychiatrist and the son of a drawing teacher. (He also looked just like Brad Pitt.) Both his parents died when he was in his teens, but he scraped together enough money to go to university, where he took courses from Carl Jung and learned cutting-edge psychoanalysis. What Rorschach added, as an artist himself, was an emphasis on the visual.

He went to museums with his friends and then asked them how they each interpreted a given painting. His dissertation was about how people feel things, in their body, as a result of what they see—whether one of his schizophrenic patients, who every time she saw someone cutting the grass felt a scythe chop her neck, or people like you and me, who might have muscle-memories of how to play a piece of music, or can feel someone’s emotions from the look on their face.

Freud thought talk-therapy could uncover who you are based on what you say and don’t say; Rorschach thought seeing goes deeper.

Working alone in a remote Swiss asylum, he crafted the test’s ten blots in 1917-18. His early versions were artistic, aesthetic, but through extensive revision and trial-and-error he simplified the blots and made them intentionally clumsier, more unusual. He added surprising colors. Some blots really do look like a bat, or two waiters, because if they were random it wouldn’t be much of a test. But a lot of latitude is left for personal interpretation.

The blots don’t look like nothing, nor like just anything—they are brilliantly made to be right on the borderline. It’s possible to see movement in the images, but not everyone sees it, the way pretty much everyone does in a picture of someone turning their head or kicking a ball. And whether or not you see it turns out to be critical.

As this suggests, there is more to the test than the scene most of us picture from old movies: A happy bunny means you’re good, an axe murderer means you’re crazy. In fact, the test is mainly about how you see, not what you see. Do you bring the image to life? Get hung up on details, or pull together a big picture? Get overwhelmed by the color? Rorschach originally called it a perception experiment, not a test at all. He realized only later that certain kinds of people tend to see the blots differently.

The test is scored by tallying up the number of Movement responses, Color responses, Wholes, Details, and so on. These formal qualities alone were enough to diagnose an illness or describe a personality. And the fact that the Rorschach can be scored at all is one of its big advantages. There is a huge amount of data to say whether an answer is common or unusual. Statistical norms have been established. You can compare different results in a way you can’t compare different free-associations on a couch. The test is science as well as art.

After the wave of skepticism in the sixties that dethroned Freud, the quantitative and numerical side of the test was emphasized, and another attempted debunking in the early 2000s resulted in the Rorschach being put on an even more solid scientific footing. Its validity has now been established more rigorously than that of any other complex psychological test. At the same time, Hermann’s blots are probably the ten most interpreted paintings of the twentieth century.

The metaphor—all those Supreme Court decisions, music videos, and fashion choices as “Rorschach tests”—came into circulation only in the sixties, with the breakdown of recognized authority. The first of thousands in the New York Times came in 1964, with a reviewer calling the task of writing a book about New York “a Rorschach.” The first test of society at large in the Times came in 1967, with MacBird, a political play about LBJ as Macbeth, “as a Rorschach for its audiences.”

Today, it sometimes seems as though everything is a Rorschach. Hillary Clinton perhaps more so than anyone in history, since at least 1993, when she told Esquire magazine, “I am a Rorschach test.” The introduction to Who Is Hillary Clinton?, an anthology published this year, called her the same thing.

After November 8, maybe we’ll stop asking the question and start focusing on the answer. The real Rorschach test, not the metaphor, is a way to move past differences in perspective. Because “What do you see?” has an answer, when you’re looking, together, at something right in front of you.

Damion Searls is the author of the first biography of Rorschach, The Inkblots: Hermann Rorschach, His Iconic Test, and the Power of Seeing, forthcoming in February, 2017.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com