This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Slaveholding and the business of slavery undergirded the economy of British North America and later the United States. Historians long have demonstrated that the institution of slavery was central to the social and economic development of the northern colonies and states; and since the 1990s there have been a number of studies on how white northerners used slave labor and were key participants in the business of slavery—the buying and selling of people and goods that sustained plantations throughout the Americas. Nevertheless, there is little public knowledge or acknowledgement that the institution of slavery was socially accepted, legally sanctioned and widely practiced in the North. For many Americans, slavery was a southern institution. The divide between scholarly work on northern slavery and public knowledge can be in part attributed to a lack of public education. K-12 history classes often sideline slavery and when it is discussed it is presented as a southern institution. There are also few public memorials to slavery in the North.

Recently, a few colleges and universities, including Brown, have acknowledged historical ties to slaveholding and the slave trade. Slaveholders and traders donated land and dominated boards of fellows and trustees. Enslaved people were put to work constructing buildings or were sold to manage institutional debt. These “recent revelations” contrast sharply with the stories that America’s leading institutions of higher education have told about themselves being places where our founding fathers began to question tyranny and form our most treasured ideas of freedom and liberty; spaces where the entrepreneurial spirit was nourished and our economic principles advanced. Administrators, students, and the general public struggle with reckoning with a history that for many generations has either been willfully disguised or unconsciously ignored. But the uncomfortable fact is that many of the country’s most valued institutions of learning were built on the backs of enslaved people of African descent. This truth is uncomfortable because it is part of an even larger uncomfortable truth—the nation was built on the back of enslaved people of African descent.

In 1764, in a report to the Lords Commissioners of Trade members of the Rhode Island General Assembly wrote “without this trade, it would have been and always will be, utterly impossible for the inhabitants of this colony to subsist themselves, or to pay for any considerable quantity of British good.” They were referring to the Atlantic Slave and West Indian trades. Rhode Island merchants provided the West Indies with slaves, livestock, dairy products, fish, candles, and lumber. The West Indian trade supplied the key ingredient, molasses, for Rhode Island’s number one export, rum.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Moreover, Rhode Islanders, who purchased African slaves with locally distilled rum, were responsible for more than 60 percent of all the North American traffic in slaves and by 1750 they held the highest concentration of slaves in New England. Ten percent of all Rhode Islanders were enslaved. A century later, in 1850, Rowland Gibson Hazard, a slave cloth manufacturer, stood in the state Assembly and said “I am by descent, by the interest of business and the ties of friendship, more closely allied with the South than any other man in this House or perhaps the state.” Rhode Islanders were the leading producers of “negro cloth,” a coarse cotton wool material made specially to minimize the cost of clothing enslaved African Americans in the South. Between 1800 and 1860, more than eighty “negro cloth” mills opened in the state. The West Indian and slave trades employed shipbuilders, sailors, caulkers, sail makers, carpenters, rope makers, painters, and distillers. Coopers made the barrels that stored the rum. Farmers used slave labor to cultivate foodstuffs for the trades. Merchants, clerks, scribes, and warehouse overseers conducted the business of the trade. The textile revolution depended on slave-grown cotton, which was manufactured into clothing for enslaved people. In Rhode Island, the business of slavery was the cornerstone of the entire economy: it was not just central to the economy, it was the economy. Rhode Islanders were engaged in the same economic activities that occupied their neighbors; however, the intensity of their involvement set them apart.

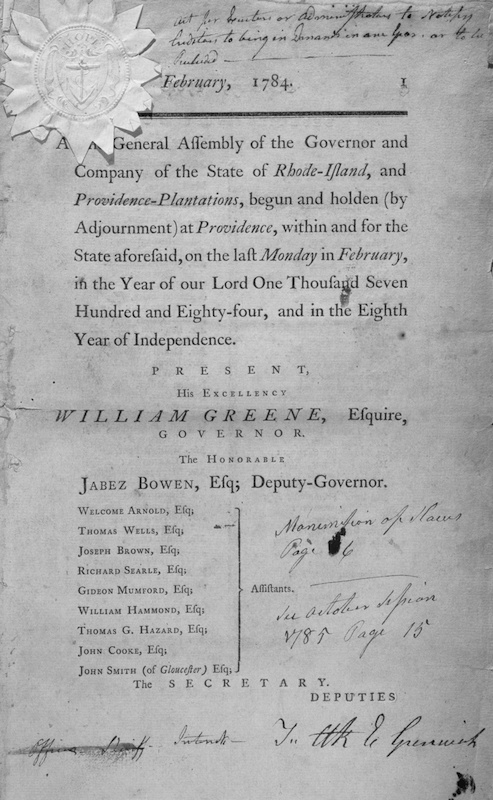

The erasure or marginalization of this history bolsters the myth that slavery was a southern institution. As a result, the experience of black people in the North has been erased. The business of slavery served to enslave black people, in the colonial period and to impoverish, alienate, and disenfranchise them in the New American Republic. Although Rhode Islanders were among the first to pass, in 1784, a gradual emancipation law ending hereditary slavery, they were among the last northerners to abolish the institution altogether, in 1842. Enslaved Rhode Islanders labored in distilleries where rum was made to purchase slaves, built the slave ships that transported enslaved Africans, served as the crew on those ships as they crisscrossed the Atlantic, and grew the food that sustained the enslaved. Yet, enslaved Rhode Islanders, like counterparts throughout the Americas, refused to be simply property; they ran away, stole, damaged property, formed families and life-long friendships. They also lobbied for their freedom, and strove to build full lives within the confines of slavery. So while the business of slavery may have defined the strictures of their lives it did not define their lives.

During the Revolutionary War enslaved people ran away in unprecedented numbers, volunteered for military service in exchange for their freedom, and lobbied their enslavers for freedom. In the new nation, in the North, most black people were free but they did not have liberty. They did not have the same protections and opportunities afforded to white people because neither the law nor mainstream white society recognized them as citizens. Black people responded to this multi-faceted marginalization by building their own institutions to bolster and protect their vulnerable communities. They fought for freedom and liberty in the name of the Constitution. They were patriots who demanded the country live up to its greater principles of liberty and justice for all. Ignoring and disregarding the experiences of black people and the centrality of the business of slavery to the northern economy allows for a dangerous fiction—that the North has no history of racism to overcome. Consequently, there is no need to redress institutional racism or work toward reconciliation.

Christy Clark-Pujara is Assistant Professor of History in the Afro-American Studies Department at the University of Wisconsin—Madison and the author of Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (NYU Press, 2016).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com