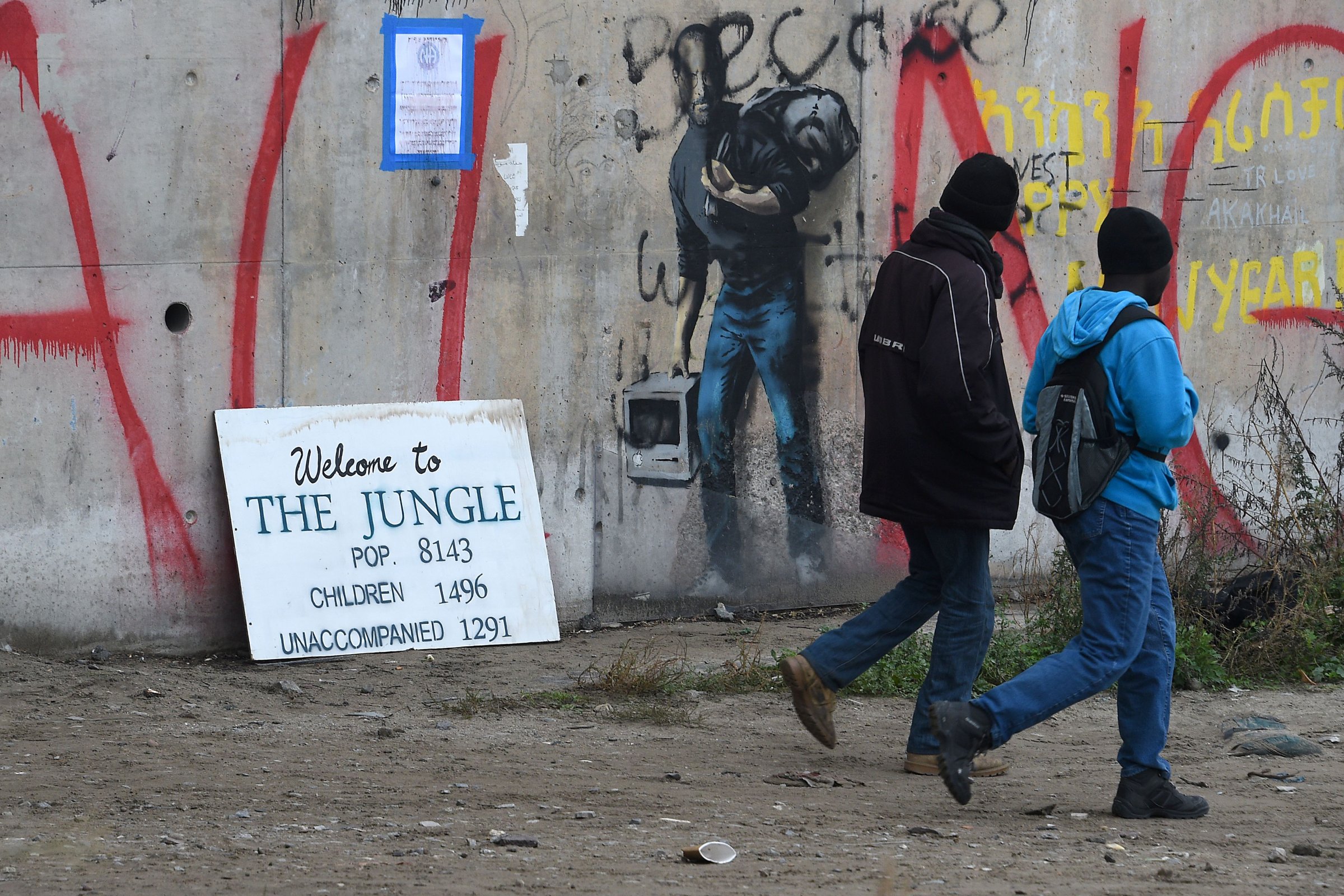

Ever since the French president François Hollande went to Calais in late September 2016 and promised that the migrant camp on its outskirts, known as “the Jungle,” would be dismantled, its residents have been preparing to be moved. On Oct. 24, queues of people who had been living in the camp in hope of crossing to Britain, waited to be registered before being transported on buses to refugee centres in other parts of France. However, it’s feared there are some residents who do not want to leave.

The camp is to be demolished. But will this police operation bring an end to people heading for Calais? Conversation editors in London and Paris asked two academics from either side of the English Channel who work on migration for their views.

We’ve been here before

Heaven Crawley, research professor at the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University:

In August 2002 I was working in the U.K. Home Office. Labour was in power and the talk was of evidence-based policy making. I had recently finished my PhD and like the other new employees sitting on the 14th floor of Apollo House in Croydon, south London, there was a sense that we could make a difference to the way things were done. Our role was to make sure that ministers were fully informed about the factors underlying the sharp rise in asylum claims to more than 84,000 that year, a figure that has not been surpassed in the period since.

And then came Sangatte, a Red Cross centre close to Calais which was established in 1999 but became the focus of the British media over the slow news days that summer. So much has changed since then—and yet so little.

Then, as now, the front pages of the daily newspapers were filled with images of people trying to cross the channel accompanied by headlines of “flood” and “invasion.” Ministers were called away from their holidays to discuss the “crisis.” It was clear that most of those at Sangatte were fleeing conflict and persecution. Quietly, and without too much fuss, around 2,000 refugees, mostly Afghans and Iraqi Kurds were brought to the U.K. and given work permits and a chance to rebuild their lives.

The Red Cross Centre at Sangatte was dismantled, the kids went back to school, normal life resumed. A few months later the refugees and migrants who had been living at the centre relocated to a makeshift camp in the woods near an industrial area that was known as “the Jungle.” The area was subsequently cleared in 2009, forcing migrants to settle in squats and makeshift shelters scattered throughout Calais—or sleep in the streets.

Fifteen years later and here we are again. As images of more than a million refugees and migrants making the desperate journey across the Mediterranean filled our newspapers and social media feeds over the summer of 2015, for those living in the U.K. the story of the Jungle became a potent symbol of the crisis gripping Europe. The numbers in the camp were tiny, never reaching more than 10,000 people in total, around 0.07% of those seeking protection in Europe. But that didn’t matter. The British public were told, repeatedly, that this was just the tip of the iceberg, that everyone coming to Europe wanted to come to the U.K. and that given half a chance they would.

There is virtually no evidence that this is the case.

Back in 2002, just before Sangatte was closed, the Home Office published a report which showed that those claiming asylum in the U.K. were attracted far more by the presence of family, language, culture and history than the prospects of accessing jobs or Britain’s far from generous welfare benefits. It made no difference. Just a few weeks later the Home Office removed the right to work for those waiting for their asylum claims to be decided, a policy that had no impact on arrivals but fundamentally undermined the ability of refugees to integrate.

In 2010, I looked again at the factors shaping the decision to come to the U.K., this time working with the Refugee Council. Again we found that existing connections to the U.K. mattered more than any policy measure ever would.

Now, in 2016, our research, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council on the dynamics of migration across the Mediterranean has shown clearly that it is the drivers of migration that have propelled people towards Europe. This is primarily conflict, persecution and human rights abuse in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Eritrea, together with escalating violence in Libya and a lack of rights and opportunities in countries such as Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. Very few of the 500 refugees and migrants we spoke to had a specific country in mind when they left their homes. Of those that did, only 6% mentioned the U.K. and most either had family already living here or could speak English and believed, rightly, that it would be easier for them to integrate.

So will there be another camp like the Jungle? The short answer is yes, almost certainly. As long as the factors that continue to drive people from their homes and prevent them from rebuilding their lives elsewhere continue and as long as E.U. member states, including the U.K., fail to provide safe and legal routes for protection and work, people will make their own way to the countries in which they have friends, family and that they feel offer the best chance to rebuild a life.

There is no obligation under international refugee law for a person to claim asylum in the first country they get to. This has simply been a mechanism introduced by the politically more powerful and richer countries of northern Europe to take full advantage of their lack of geographical proximity to the epicentres of conflict and violence.

The Jungle may not return to Calais – where the fence that has already been built to prevent people accessing the trains and lorries crossing the English Channel is now being extended and reinforced with concrete at the expense of the British taxpayer. But all of the evidence from 25 years of research on this issue tells me that people who are sufficiently desperate or motivated to move, who have no sense of a future or an alternative, will always find a way around the barriers that are put in place to stop them. It’s possible, if expensive, to build a wall around a port, less so a country.

But a long-term solution is possible. Europe, and all of its member states, need to listen to the evidence about why people are on the move in such large numbers and devise policy solutions which tackle the drivers of primary and secondary migration rather than expending huge resources and political energy on keeping people out. They have a huge range of policy tools at their disposal – refugee resettlement, family reunification, humanitarian visas, temporary work permits, educational visa – most of which have stayed firmly in the box. It’s time they were taken out and put to work.

Calais: the show of force continues

Olivier Clochard, researcher at the CNRS (Migrinter), Université de Poitiers:

History is repeating itself. The biggest camp that the Calais region has seen in 20 years is going to be dismantled in the same way as those that preceded it. But once again, the destruction of this living space will not resolve the region’s migration situation.

Whether it was during the destruction of the Sangatte camp in 2002, squats and encampments in Calais in the winter of 2015 or the Jungle this winter, the French and British governments continue trying to persuade the public that police operations will resolve the migration situation.

Each of these operations has sent people away from the Calais area, to other French regions, other EU member states or even back to their home countries – so temporarily reducing migration pressure. But the Calais area remains a transit zone, where people trying to find better living conditions face obsessively increasing migration controls.

In Calais and its surroundings, women, men and children continue to arrive for the same reasons which brought the refugees before them – and which numerous studies have relayed: they speak English, or have members of their family or friends living in the U.K.

The members of the current French government, very critical when they were in opposition, have adopted the restrictive methods of their predecessors. With the help of the U.K., France is reinforcing its migration controls by building walls and deploying sniffer dogs. But this is exacerbating the tensions in the region, where the presence of the French police is already very consequential. And all this has not stopped people from attempting to cross into the U.K. via the Channel Tunnel in recent months, despite a statement to the contrary in early September by the French minister of the interior, Bernand Cazeneuve.

This ministerial artifice is also playing out through the process of moving migrants to special centres, known as centres d’accueil et d’orienation (CAO), spread across France. A year ago, the French government promised that it would not apply the EU’s Dublin regulations to the Calais migrants, meaning it said it would not expel them back to the first European country they arrived in to submit their claim for asylum. This promise was made to persuade people to start leaving the camp and to claim asylum in France – but it has not been respected and associations close to the CAO have reported a number of examples of people who have been deported or threatened with it.

And despite a promise in October 2015 from the French prime minister, Manuel Valls, that those who provide support to the refugees would not be arrested and criminalised, this has continued. Volunteers have also been regularly subject to reprisals – they have been searched, questioned, arrested, and faced courts summons. This is despite the fact that since the early 1990s, the majority of the food supplies and legal support for migrants living in and around Calais has been provided by these volunteers. The activists from the No Borders movement—among others—are regularly targeted by the authorities, despite the fact that their work defending human rights has been recognised in France and internationally.

Two years ago a number of organisations wrote a letter to Valls and Cazeneuve, reminding them that the French government lacks courage by refusing to take into account what the refugees and those associations offering alternative solutions are saying about the situation. These include reform of the EU refugee rules, better information for migrants upon arrival, and the provision of better state support for migrants and refugees living on the streets.

Misinformation is to democracy what propaganda agencies are to totalitarian states. In the face of these government manipulations, the rupture between those volunteer organisations who have a good understanding of the migrant situation in Calais and the government has never been so serious.

Heaven Crawley, Research Professor, Coventry University and Olivier Clochard, Chargé de recherches à Migrinter (CNRS), Université de Poitiers

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com