This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

On September 5, AD 394, a violent tempest blew dust in the faces of an army led by a barbarian general who had taken over the western half of the Roman Empire. It was so fierce it blinded them, made their javelins fall short of the enemy and even wrenched the weapons from their hands.

The man who benefited was the enemy commander, the Christian Theodosius I, ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire, based in Constantinople. On the previous day, the barbarians had had much the better of the battle, thanks they believed to their pagan gods, whose statues they had erected on the field.

Now they became convinced that the Eastern Emperor’s Christian god had taken up arms against them, and they were routed, allowing Theodosius to become the last man to unite the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, and ensuring the final victory in Rome of Christianity over the old pagan gods.

This was just one of the occasions when a storm meddled with the course of history. In 480 BC, the Persian Emperor, Xerxes the Great, sentenced the waters of the Dardanelles to 300 lashes, when, stirred up by a tempest, they washed away the mile-long pontoon bridges he had built to get his army across into Greece.

Storms also played a part in the crucial defeat of the Roman army by German tribesmen in the Teutoburg forest in AD 9, which halted the expansion of the empire at the Rhine and cemented the division of Europe into Germanic north and Latin south.

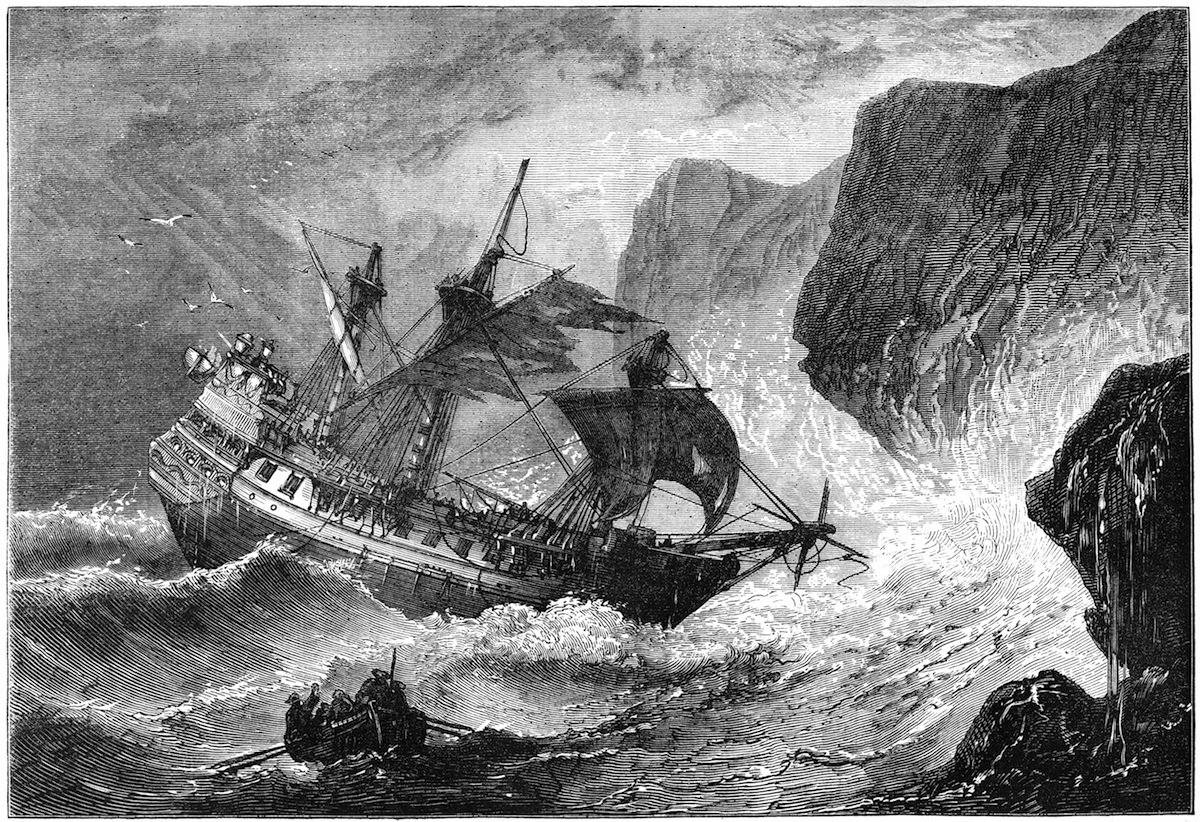

Xerxes was not the only would-be conqueror to have his plans blown off course by foul weather. When Philip II of Spain sent his great Armada against England in 1588, summer storms – the Spaniards said it was more like December than June – delayed the invasion by more than two months.

The English fleet was by then well-prepared and won an important victory off Gravelines. Then came the storms that turned a defeat into a disaster, driving the Spanish fleet around the coasts of Scotland and Ireland as it tried to return home. Dozens of ships and thousands of men were lost. “God breathed and they were scattered,” said the celebratory medal struck by Elizabeth I.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

What the Japanese called kamikaze – divine winds – twice saved Japan from being overrun by the Mongol descendants of Genghis Khan, as typhoons destroyed their invasion fleets in 1274 and 1281.

But storms did not interfere with history only by disrupting military actions.

In 1609, a convoy on its way to the English colony of Jamestown, Va., was blown off course, with the result that they discovered Bermuda – still a British overseas territory but now a holiday paradise and tax haven. The episode seems to have inspired Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest.

A more disruptive consequence was what happened after French harvests had suffered from floods and droughts and a devastating hailstorm on 13 July 1788 killed people and livestock and destroyed many crops. Bread hit famine prices, reduced tax revenues bankrupted the government, and Louis XVI had to call the Estates-General, the French equivalent of parliament, for the first time in 175 years, setting the country on the road to revolution.

But, of course, that was all a long time ago, and during the last hundred years, weather forecasting has improved immeasurably, so surely that has diminished the ability of the elements to rewrite history?

Certainly during World War Two, the combatants devoted huge resources to predicting storms, with the U.K., for example, having a top secret Thunderstorm Location Unit, said to be able to record every major flash of lightning up to 2,000 miles away. But even then Allied fleets were caught in typhoons off the Philippines in 1944 and off Okinawa in 1945.

And 35 years later, this maddening refusal of the weather to behave as expected messed up President Jimmy Carter’s attempt to rescue American hostages from Iran in 1980, as an unexpected dust storm knocked out a quarter of the helicopters.

Since then, of course, computers have got more and more powerful crunching ever bigger mountains of weather data, but as for eliminating unexpected storms, that does not appear to be on the horizon at present. Frank Marks, director of the NOAA’s hurricane research division says we are still learning just how complicated they are: “It’s pretty humbling, considering how little we know.”

John Withington, a graduate of Oxford University and an award-winning television, radio and newspaper journalist, is the author of a number of books on the history of disasters, including A Disastrous History of the World (published in the USA as Disaster!), A Disastrous History of Britain, London’s Disasters, and Flood: Nature and Culture. His latest book is Storm: Nature and Culture.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com