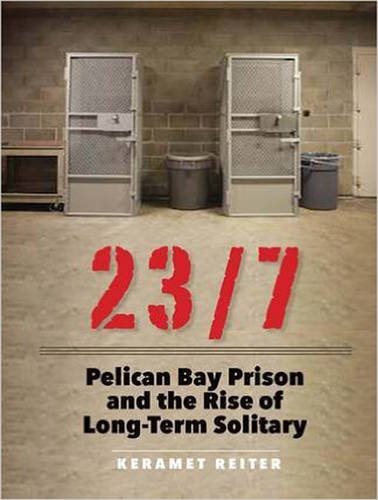

According to estimates from federal agencies, there are tens of thousands of prisoners in solitary confinement–put there not by judges or juries but at the discretion of prison administrators. Often the conditions are extreme: one California prisoner, Todd Ashker, spent more than 20 years in a cell the size of a wheelchair-accessible bathroom stall, with the lights on 24 hours a day.

It’s easy to dismiss solitary as just another consequence of committing a crime. But that logic ignores broader costs. First, it’s expensive. A year in solitary averages $75,000 per prisoner–about three times the average cost of incarceration. Second, it’s dangerous. Isolated prisoners often become psychotic from sensory deprivation. And third, it can be invisible to oversight, enabling abuse. Vaughn Dortch, another California prisoner, publicly alleged that after he had a mental breakdown in solitary, officers dunked him in scalding water, scrubbed him with wire brushes and joked about turning him from a black man into a “white boy.” (The prison disputed the charge, but a class action found that it had subjected prisoners to cruel and unusual punishment.)

These conditions aren’t bad just for prisoners. They’re bad for everyone. Because when a solitary prisoner’s criminal sentence expires, he is released directly back into the community, ill prepared to adjust.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com