There is something uniquely horrifying when the guidance system at the heart of a so-called “smart bomb” is a human brain. It’s a shock to see ISIS militants driving vehicles toward Iraqi and Kurdish forces trying to kick them out of Mosul—and blowing themselves, and their enemy—to smithereens. In the first two days of the Iraqi-led offensive to retake Iraq’s second-largest city, ISIS has made multiple claims of such suicide bombings. Their number is only likely to grow as the Iraqis, aided by U.S. advisers and air power, push deeper into the city of 1 million.

The normal logic of war evaporates on a battlefield salted with suicidal fighters. “The most powerful tool any soldier has is the ability to utilize lethal force, if needed, to eliminate a threat,” says Rob Kumpf, an ex-Army sergeant who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. “But a suicide bomber takes away that threat. If someone is no longer afraid of being killed, and now seeks out their death as part of their mission, how do you stop them?”

And their presence on the battlefield changes the calculus for those on the other side. “It’s an uglier kind of fighting,” says Alex Lemons, a former Marine who fought in Fallujah in 2004 during one of his three Iraq combat tours. “When you fight someone who wants to survive, I always felt like my teammates and I could make better decisions or predictions.” A potential suicide fighter could be feigning wounds and just waiting for U.S. troops to get close enough so he could take a shot at them, or approaching them in a vehicle at high speed, forcing split-second decisions that could kill civilians. “The idea of a gentleman’s war goes out the window,” Lemons says. “In point of fact, you would much rather obliterate every building, torch every plant and leave no one alive rather than patrol in at close quarters for an unpredictable encounter with a madman with no intent to surrender.”

But do such attacks constitute a sound military strategy? Tactically, yes. Strategically, no.

Tactically, meaning on an individual basis, suicide attacks are far more deadly than non-suicide attacks. “On average, suicide attacks in 2015 were 4.6 times as lethal as non-suicide attacks,” the U.S. government noted in its most recent annual global terror analysis. And the problem is growing. “The number of suicide attacks increased by 26%, from 575 in 2014, to 726 in 2015,” the report said. “Suicide attacks in 2015 killed 6,712 people, including 1,722 perpetrators, and wounded more than 10,000 people.”

But suicide attacks don’t work strategically, meaning their gains usually can’t be sustained. They require a degree of fanaticism among those carrying them out that keeps the stockpile relatively small.

Yet they are potent weapon for zealots willing to die for a cause. In the first eight months of 2016, Amaq, an ISIS news agency, said Islamic State fighters had carried out 729 “martyrdom operations” in Iraq, Libya and Syria.

Two of every three involved car bombs, as opposed to individuals wearing explosive belts or vests. There’s military logic to ISIS suicide bombers’ choice of what in military lingo is called the “platform” to deliver death: vehicles are faster and can carry more explosives (they also offer suicide bombers some protection as they approach their target, allowing them to get closer in the final seconds; nothing is as demoralizing as being a suicide-bomber dud, although it’s generally a short-lived regret).

The American way of war has a tough time comprehending the willingness of a combatant to kill him or herself. After all, that’s the whole logic, such as it is, of “body counts”: if we kill more of the enemy than the enemy kills of us, we’re winning. Right? “Suicide fighters are absolutely terrifying as their actions defy our thoughts on reason,” ex-Army grunt Kumpf says. “A suicide attacker won’t stop when you point your rifle at them, they won’t stop when you start firing, unless you’re able to kill them from a distance, and are still going to complete their mission to some extent. That’s terrifying.”

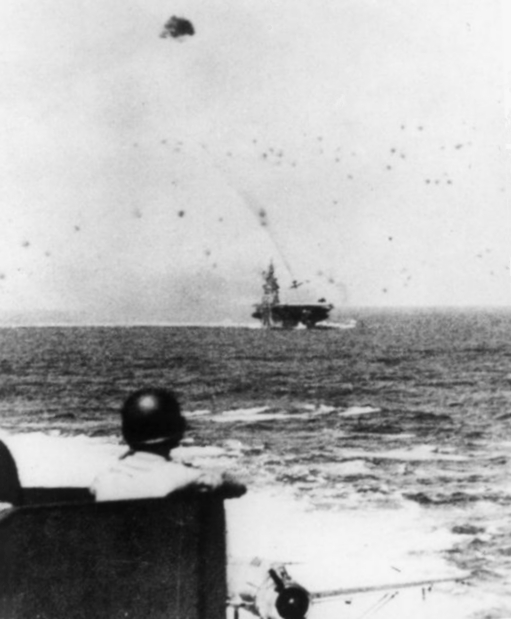

Suicide bombers trace a fascinatingly perverse arc through recent history. While death has always been a part of military life, “the Japanese kamikaze program was something different,” according to a 1971 U.S. Navy study of the manned aircraft that dive-bombed into allied ships in the final 10 months of World War II. “To wage an entire campaign as an exercise in mass, deliberate suicide had no precedent.” Nearly 3,000 Japanese kamikaze pilots, according to one U.S. account, sank 34 Navy ships, damaged 368 others, killed 4,900 sailors, and wounded more than 4,800. Roughly one in seven kamikazes hit their target, and nearly 8.5% of those hit sank. The attacks constituted a last-ditch effort to prevail in a war many Japanese felt was lost.

“As a direct result of the increased kamikaze program, nervous tension on ships of the line ran high throughout the Philippine invasion,” according to a U.S. Navy medical survey of the attacks. “Increasingly, it was noted by medical officers that numbers of men reported to sick call for `vague mental complaints’” that read very much like a list of PTSD symptoms: “Irritability, depression, anxiety, and fatigue.” The top doc aboard one light-aircraft carrier reported “that time for the execution of various jobs had increased by as much as 50%” due to the kamikaze threat.

Many Japanese viewed such a death as part of the Bushido code embraced by their samurai ancestors. “For someone who had a good life, it is very difficult to part with it,” one kamikaze pilot wrote. “But I reached a point of no return. I must plunge into an enemy vessel.”

Not all suicide fighters may be true volunteers. “I saw a lot of prescription drugs —empty boxes and/or bottles—when I was doing battle damage assessments after firefights in Sangin in 2010 and 2011,” says former Marine sergeant William Treseder of his Taliban-fighting days in Afghanistan. “These guys often required an altered mental state just to screw up the courage to shoot at us. I can only imagine how much it takes to get one of them—even the children and mentally unstable individuals they like to use—to strap on a bomb.”

But some are cool and calculating. Fifteen years ago a band of 19 suicide hijackers killed 2,996. Suicidal fighters never cropped up on the radar screens of U.S. authorities, a lesson that ended bitterly with box cutters on Sept. 11, 2001. Until that day, U.S. policy had been to negotiate with anyone who seized an airplane. “The strategy operated on the fundamental assumption that hijackers issue negotiable demands (most often for asylum or the release of prisoners),” the 9/11 Commission Report concluded in 2004. “As one FAA official put it, ‘suicide wasn’t in the game plan’ of hijackers.”

As the battle for Mosul unfolds, there will be more suicide attacks, often yielding horrific videos that are more about generating propaganda than documenting anything militarily significant.

But ultimately, suicide on the battlefield has a limited lifespan. A Japanese military officer noted a key shortcoming in March 1945, halfway through his nation’s kamikaze campaign that ended only after the U.S. dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war. “A plane should be utilized over and over again,” he wrote. “Otherwise, you cannot expect to improve air power. There will be no progress if flyers continue to die.” In that, he echoed the observation of the Tacitus, 2,000 years before. Only if one survives the battle, the Roman historian said, can one live “to fight another day.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com