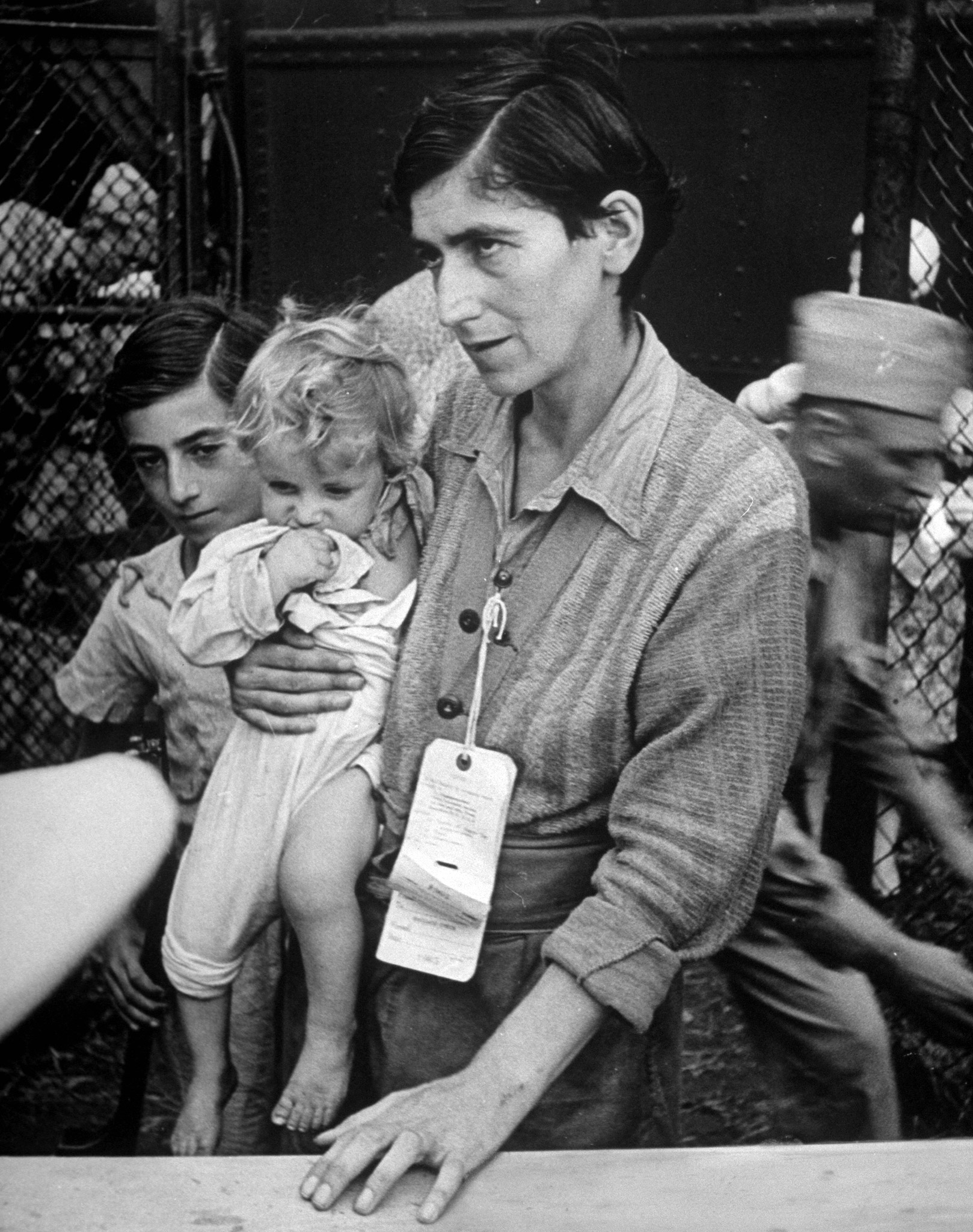

On World Refugee Day this past June, when LIFE republished a set of photographs taken in 1944 by Alfred Eisenstaedt at a camp for World War II refugees in Oswego, N.Y., the first image was the one seen here: a woman, identified as Eva Bass, arriving with her children.

Though many people saw the gallery, a few people had particular interest in it: the children in that photograph, Gloria Fredkove (born Yolanda Bass, 15 months old in the photo) and Jack Bass (born Joachim, nearly 12 years old at the time of the picture).

And, it turns out, that photograph played a major role in Gloria Fredkove’s life.

“I had shown this picture of my family in LIFE Magazine to a good friend of mine. This was back in the early ‘80s. She called me and said, ‘Gloria, I’m reading a book about refugees during World War II and the picture that you showed me is in it and it mentions your name and everything,'” Fredkove tells LIFE. “I was shocked. I thought this was a small thing that happened that really nobody noticed. And one of the reasons I thought that was that my mom didn’t really say too much about us coming over.”

The book was Haven, by Ruth Gruber. As Gruber explains in the book, Eva Bass—Fredkove’s mother—was a singer in Paris who fled to Italy, where she was put in prison for her politics and religion. “Carrying Yolanda in one arm and, when Joachim could no longer walk, carrying him in the other, she had trekked for sixty kilometers through the fighting lines to reach the Allies,” Gruber wrote. (Bass later Americanized her children’s names.)

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Fredkove, who was too young to remember Oswego, learned much of what she knows about her own family history from Gruber, but she says the story is still full of holes. For example, though Fredkove had known that her mother had been pregnant on the crossing and gave birth in Oswego to a baby girl, who was subsequently placed for adoption—perhaps against Bass’ wishes, Fredkove suggests—she didn’t begin to look into what had happened to her sister until the 1980s, and still has many questions. Fredkove is also in the dark about the identity of her father.

“Those are pieces that make me at different times angry, sad, depressed—but I have had a pretty good life,” she says.

As for the photo itself, that’s something Fredkove has also had cause to see in a new, brighter light. “I used to be really guarded about it when I was younger. I didn’t want anyone to see it. I had shame about it, because it’s a very sad picture,” she says. “I didn’t want people to feel sorry for me, and I didn’t want people to judge me as being different. I always wanted to fit in as a child, and the minute you see that picture connected with the word refugee, you are an outsider.”

Through learning about her history from Gruber’s book, and beginning to speak to schoolchildren about the importance of never forgetting the Holocaust, she began to see the image as a valuable document and something to share rather than hide.

“I realized that this story is not just about my family,” Fredkove says. “It’s about people who are fleeing from injustice and prejudice and persecution and death. And that is a universal—it’s not just about me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com