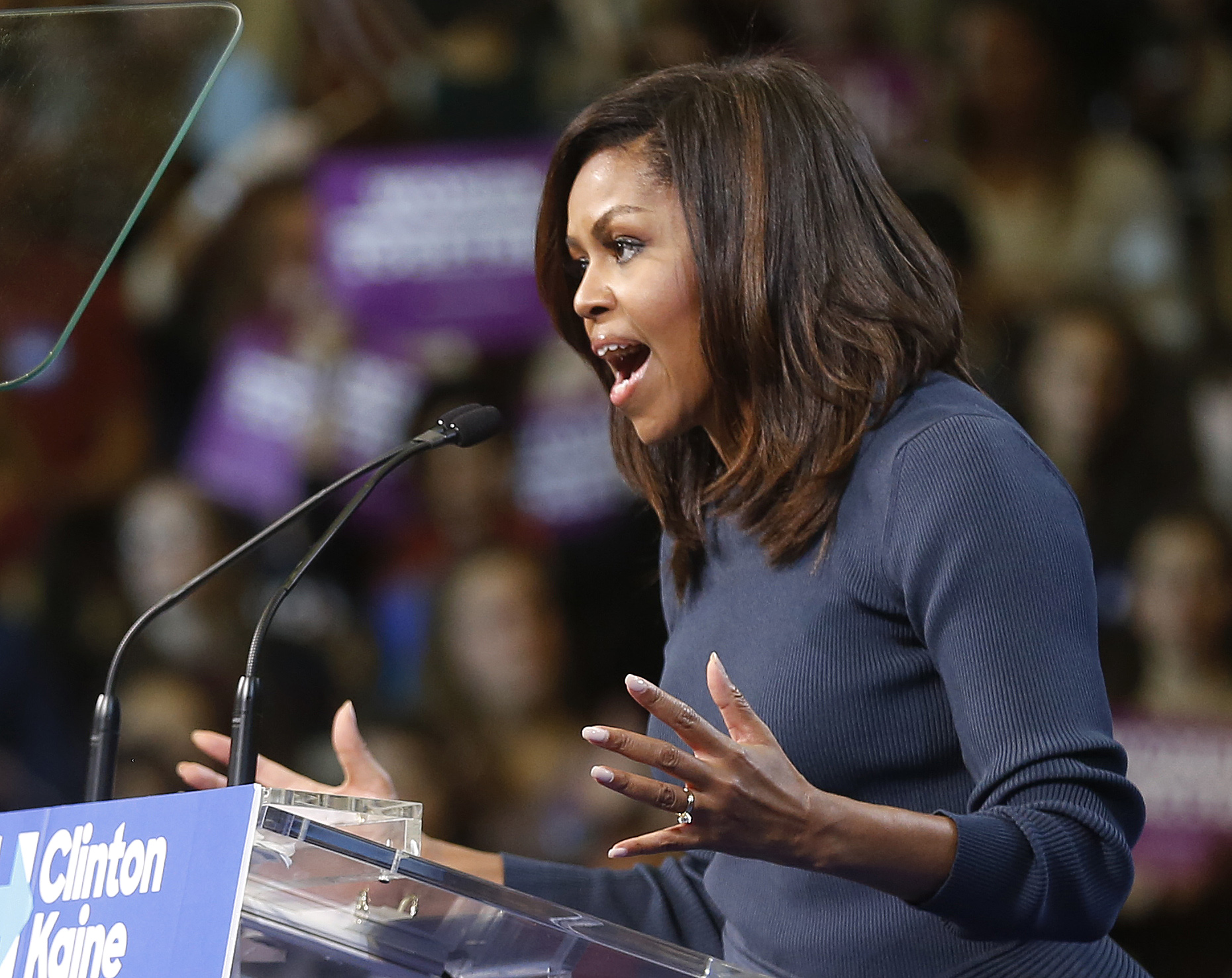

At a rally for Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton on Thursday in Manchester, N.H., First Lady Michelle Obama condemned recorded comments from Republican nominee Donald Trump as shocking to hear in 2016. Though Trump has characterized his statements—including the idea that a “star” can get away with doing “anything” to women— as “locker-room banter,” Obama rejected that assessment, instead positioning Trump’s comments within a long history of the harassment of American women by men in positions of power.

“It reminds us of stories we heard from our mothers and grandmothers about how, back in their day, the boss could say and do whatever he pleased to the women in the office,” Obama said, “and even though they worked so hard, jumped over every hurdle to prove themselves, it was never enough.”

No matter what you think of the locker-room defense, Obama is right that there was a time when bosses could legally get away a lot.

As legal scholar Reva B. Siegel explains in Directions of Sexual Harassment Law, though people may think of workplace harassment as a modern problem, “the practice of sexual harassment is centuries-old.” In U.S. history, it encompasses everything from the “sexual coercion” of enslaved women to the predation endured by women in the meat-packing industry, as described in Sinclair’s 1905 exposé The Jungle. But, throughout much of that history, women were often blamed for the problem and had little recourse available, as Siegel writes: “In short, the law assumed that women in fact wanted the sexual advances and assaults that they claimed injured them.”

Even when the 1964 Civil Rights Act was signed—banning discrimination on the basis of sex, among other reasons—there still “wasn’t any recognition that sexual harassment was a form of discrimination,” as Joseph Fishkin, professor of law at the University of Texas at Austin, puts it.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The writer Lin Farley is credited with coining the term “sexual harassment,” while testifying in 1975 before the Commission on Human Rights of the City of New York. Farley was part of the group Working Women United, formed at Cornell when former university employee Carmita Wood “filed a claim for unemployment benefits after she resigned from her job due to unwanted touching from her supervisor,” as TIME has previously reported. “Cornell had refused Wood’s request for a transfer, and denied her the benefits on the grounds that she quit for ‘personal reasons.'”

It was in 1979 that scholar Catharine MacKinnon wrote Sexual Harassment of Working Women, making headlines by laying out a legal theory arguing that “treating women not as workers but as sexual playthings on the job is a form of discrimination based on sex that violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act,” as Fishkin summarizes.

In 1980, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) published sexual harassment guidelines, and in the 1986 case Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, the Supreme Court essentially acknowledged MacKinnon’s view, that harassment was discrimination. “All kinds of lower court judgments before then were saying things like, ‘Oh well you weren’t fired because of your sex, you were fired because you didn’t sleep with your boss,'” Fishkin says.

After that, employers began to get the message: they’d better institute policies to prevent that kind of thing from happening at their offices, as Vicki Schultz, professor at Yale Law School and author of the 1998 Yale Law Journal article “Reconceptualizing Sexual Harassment” explained to TIME. But, she says, it was the 1991 spectacle of Clarence Thomas’ Supreme Court confirmation hearings, during which Anita Hill alleged he had harassed her, that really changed the national attitude toward whether sexual harassment was a real problem.

In the years that followed, the Supreme Court would go even further, for example, by lowering the burden of proof for harassment claims and providing further incentives for employers to institute and enforce firm anti-harassment policies.

Nowadays, Schultz argues that—though harassment is, as Michelle Obama so soundly argued, still a major problem—the law has significantly evolved and, perhaps more importantly, society has finally reached a point where an average person “looks at allegations and says ‘gee, that’s sexual harassment,’ even if it’s not occurring in a workplace,” she says,

“People understand that having something hostile or demeaning directed at you because you’re a woman or a man is sexual harassment,” she says, “regardless of whether a formal legal complaint could be filed.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com