The rituals of grief distract the mind. As Thai subjects mourned the world’s longest-serving monarch, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who died on Oct. 13 at 88 years of age, protocol unfurled with somber ceremony. Tens of thousands of black-clad grievers lined the streets near the Grand Palace in Thailand’s capital of Bangkok on Friday to pay tribute to a King who had reigned for 70 years. For nearly all those gathered, he was the only national monarch they had known — and he was beloved.

Despite temperatures so broiling that shoes stuck to newly laid asphalt, Thai citizens paid tribute with a traditional bathing ceremony held at the palace complex’s Temple of the Emerald Buddha in which they poured sacred water under his portrait. The King’s body would also undergo cleansing Buddhist funerary rites at the same temple. “We have lost our father,” says Pornpimon Kanthawong, a 58-year-old masseuse who had staked out her square of pavement in front of the Grand Palace at 5 on Friday morning. “I want to wake up from this nightmare.”

Read More: Four Things to Know About Thailand’s Next King, Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn

The Kingdom of Thailand has entered its period of national mourning. Officially, it is to last a year. Thais changed their Facebook profiles to squares of black. Bangkok residents donned the same dark hue, and civil servants will wear black for a year. Workers gathered armfuls of inky bunting to frame billboards of the King that loom across the city. Soi Cowboy, the Thai capital’s Vietnam War–era red-light district, was mostly closed for business. Bangkok convenience stores refrained from selling alcohol. Throughout the day, local TV stations aired nothing but royal footage highlighting the King’s ascetic public life — the irrigation projects he inspected or the farms he promoted through rural-development schemes.

The Thai King had been ill for years. He had not appeared in public since January. His death was hardly unexpected. Still, the cruelty of mortality has been made keener by Thailand’s current state of affairs. King Bhumibol’s reign has been cast as an era of remarkable stability in a region once rife with civil war, communist fervor and genocidal frenzy.

It is true that under its constitutional monarch, who took on an unofficial role as national unifier, Thailand avoided the kind of bloodshed that tore apart nearby nations like Cambodia, Vietnam or Indonesia. But in recent years, Thailand has been riven by political protest. Dozens have died in civil violence. Repeated efforts to vote in political leaders have been thwarted by a military with a penchant for staging coups.

Read More: Thailand Bids Farewell to Beloved King Bhumibol Adulyadej

The latest putsch was carried out in May 2014, and junta leader General Prayuth Chan-ocha now serves as Thailand’s Prime Minister. “I could not sleep last night because I was so worried,” says Wasanna Yenchai, a 55-year-old employee of the Ministry of Commerce who was paying her respects at the Grand Palace. “Regardless of their [political] colors, people love His Majesty. I do not know what will happen now that he is gone.”

The Thai King’s designated heir is Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, who rushed back to Thailand from Germany where he spends the bulk of his time. In what is considered a somewhat surprise development, the Crown Prince — a qualified military pilot who was schooled overseas like his father — will not ascend to the throne until “an appropriate time,” according to General Prayuth, because the chosen successor wants “time to deal with his grief and express his sadness.”

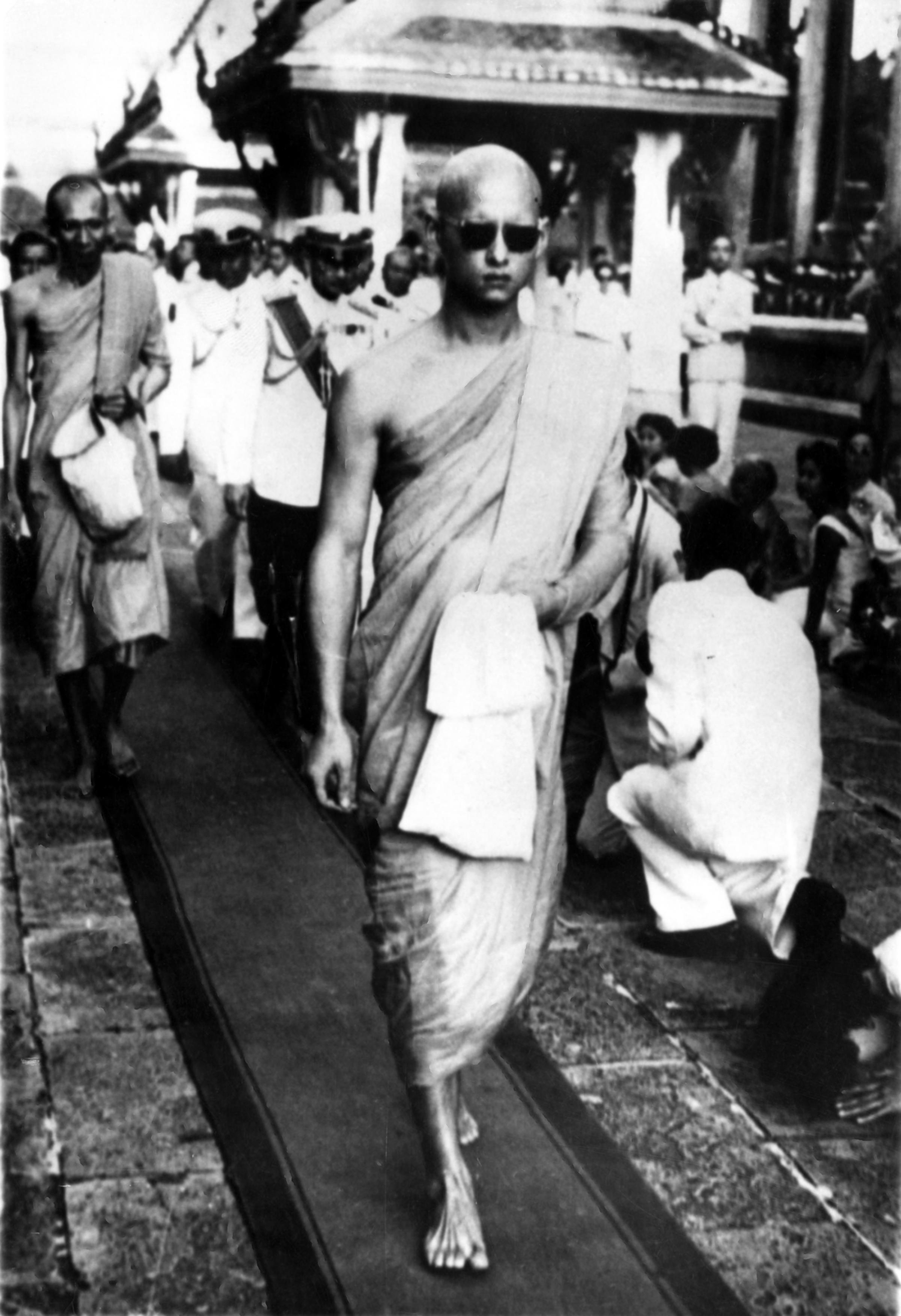

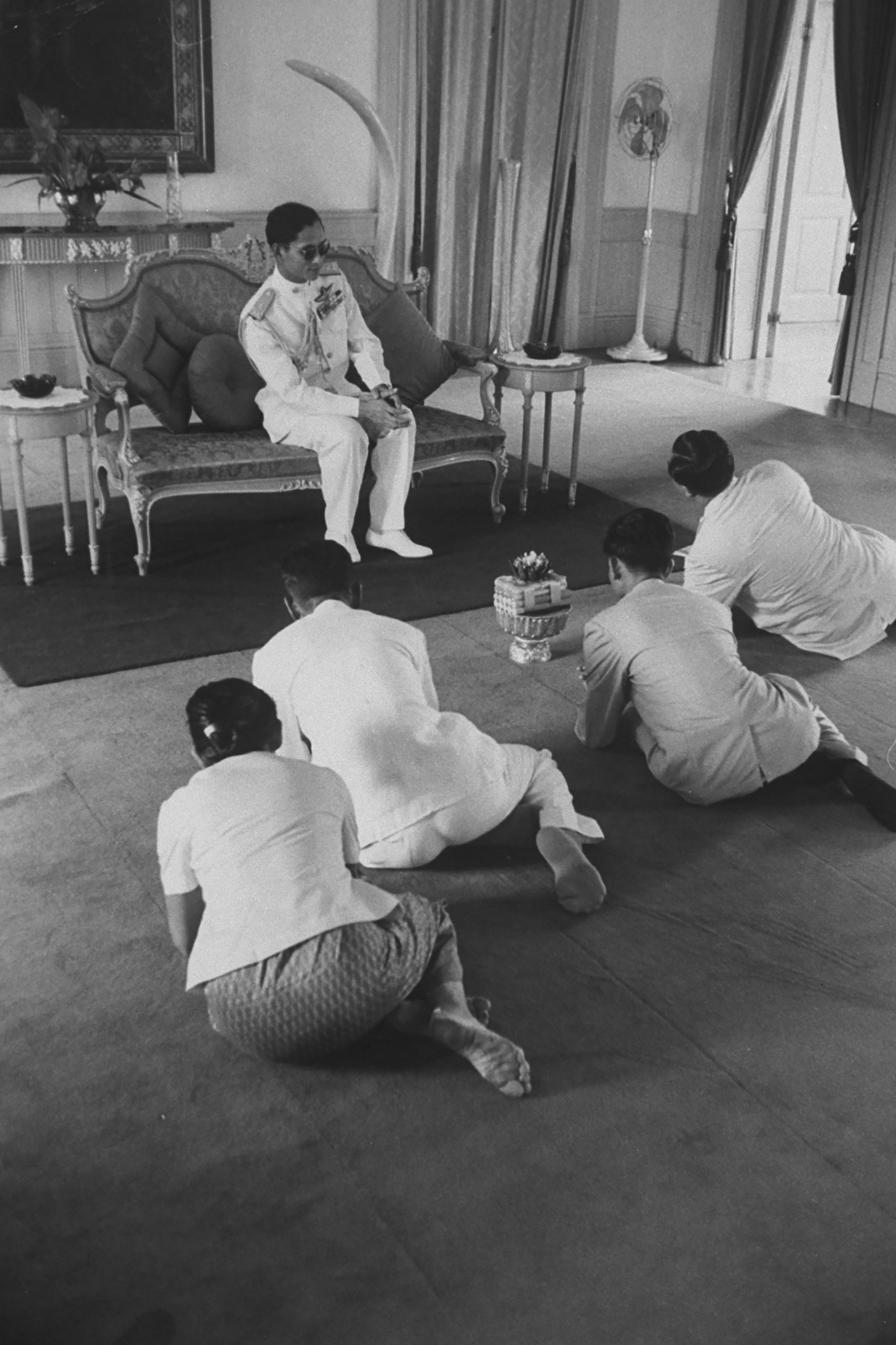

King Bhumibol’s image as an austere attendant to Thailand’s poor has not been passed on to his 64-year-old son, who will inherit the world’s largest royal fortune. Over the decades, the Thai King often traveled to remote swaths of Thailand, where he advised on rural-development projects. He was pictured in simple short-sleeved shirts, a camera slung around his neck to record the latest agricultural or hydrological ventures. Of the King’s three daughters and one son, Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn has most followed his example, projecting a humble image and earning admiration from the Thai populace. “She is her father’s shadow,” says mourner Wasanna.

Life in Pictures: King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand

So far, the Crown Prince has not commanded the kind of mass public devotion his sister has. It’s even harder to imagine Thais venerating the son as they did his father. King Bhumibol’s solemn image graces nearly every Thai home and office. His profile is on all denominations of the baht, the Thai currency. The thrice-married Crown Prince, meanwhile, has found himself starring in a leaked video, blocked online in Thailand, in which he and his then wife, the former Princess Srirasmi, ate cake with their pet poodle. Since that video clip, in which his wife was barely clothed, the Crown Prince has split from his consort, who has been stripped of her princess status. Members of her family have been jailed for insulting the monarchy, following allegations of corruption. The poodle — which had a military rank, according to leaked U.S. diplomatic cables — died last year.

Thailand’s extended bereavement also serves as a diversion from existential worries about the nation’s future. The ruling junta has locked up opponents to military rule with little due process. With the backing of a national referendum, the National Council for Peace and Order, as the junta styles itself, has delayed elections until the end of 2017, at the earliest. The King’s death could mean a further postponement of polls.

Some of the nation’s recent political fractiousness no doubt stems from jockeying ahead of the King’s expected death. In broad-brush terms, the nation is split between supporters of royalist elites and populist forces led by Thaksin Shinawatra, the exiled former Prime Minister who was convicted in absentia of abuse of power following a 2006 army coup. But the divisions are not so simple. For instance, some Thais believe that Thaksin tried to burnish his relationship with the Crown Prince, angering members of the influential Privy Council that manages royal affairs.

Much cannot be said in Thailand. The military can prosecute anyone who “undermines public peace and order.” Thailand also boasts some of the world’s most draconian lèse majesté laws. Anyone can be accused by any person of maligning the king, queen, heir to the throne or regent. Writers sometimes resort to pseudonyms to avoid the threat of prosecution. The King himself said in 2005 that he was not above criticism. But the number of lèse majesté cases has only increased since then.

In 2010, while giving a lecture in the U.S., former Thai Foreign Minister Kasit Piromya said that Thais should “talk about the institution of the monarchy, how it would have to reform itself to the modern globalized world.” He went on: “Let’s have a discussion: What type of democratic society would we like to be?” But fast-forward six years, and Thailand is no democratic society. Prayuth has offered to execute journalists who “do not report the truth.” The junta blocks thousands upon thousands of websites with content deemed sensitive or defamatory to the monarchy. Previously elected governments did the same. In the resulting blank space, rumors and questions proliferate. Chief among them is this: Will Thailand again descend into violence?

Oct. 14, the day on which Thailand began its official mourning of its revered King, also marks the anniversary of a 1973 slaughter of student-led Thai protesters by forces controlled by autocratic Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn. Not far from the Grand Palace is a memorial marking the massacre of at least 77 civilians, many students. In that case, King Bhumibol intervened, a rare departure from his official apolitical stance. He and Queen Sirikit allowed protesters to take refuge in their palace complex. The field marshal went into exile.

But three years later, Thanom returned. Protesting students at Thammasat University in Bangkok were again killed. Toward the very end of his life, the King said little — or, more likely, could say little, given his grave health — as yet more political upheaval gripped his nation. “We must pray that our nation stays whole,” said a 22-year-old student nicknamed Nok, who stood in front of the Oct. 14 memorial on Friday, as black-clad mourners streamed past heading to the Grand Palace. “We must all pray together.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com