Slavery in the United States was a cruel abomination under which millions of people suffered, and its scars linger to this day. It inevitably provoked resistance and reaction, of which one striking example was the rebellion led by Nat Turner, an enslaved Virginia preacher, in 1831. That rebellion, the subject of the new movie The Birth of a Nation, killed 60 white men, women and children, most of them families sleeping in their beds, and led to the execution of a roughly equal number of black rebels and the reprisal murders of additional black people.

Few famous criminals have left behind a more detailed record of their thoughts than Nat Turner, who was deposed at length by a local lawyer after his capture about six weeks after the rebellion. His confession is an extraordinary historical document, but filmmaker Nate Parker chose to disregard a great deal of it making his movie. Though the changes may make Turner more sympathetic, they do not, in my opinion, help Parker’s fellow citizens understand this horrifying event from our past. To outgrow the worst aspects of our history and to avoid reviving them, we would do well to understand it as it really was.

Turner’s confession reveals him to be an intellectual prodigy, a man of truly aristocratic temperament, and a religious fanatic. Turner, who was born in 1800, had begun to read voraciously at a very early age, and was the wonder of all who knew him, white and black. Indeed, as he explained to his interlocutor Thomas Gray, his fellow slaves had deferred to his judgment even in his childhood. He was obsessed with religion and the Bible, and as he explained, he heard the voice of the Holy Spirit and had visions more than once. He became convinced in early manhood that he was destined to do great things. Though Turner ran away from an overseer for some weeks at one time, he returned, much to the surprise of his fellow slaves, to pursue that destiny. In the film, Turner’s sense of his own great destiny is missing.

The film shows Turner driven to rebellion by repeated acts of cruelty, including the gang rape of his wife by white men and a severe beating from his master. His confession not only says nothing about any such incident, but instead states, “Since the commencement of 1830, I had been living with Mr. Joseph Travis, who was to me a kind master, and placed the greatest confidence in me; in fact, I had no cause to complain of his treatment to me.” But a year and half earlier, in 1828, Turner said he had had his greatest visitation from the Holy Spirit, who commanded him to “fight the serpent, for the day was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.” He interpreted that as a signal to kill white slave owners and their families, and he interpreted a total eclipse of the sun as a final call to action.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

He gathered a band of conspirators, which the film shows. They initially had hoped to begin their rebellion on July 4, 1831, but were delayed until August. The rebellion began with the murder of Turner’s master Mr. Travis, his wife, and three children by Turner and his confederates. Parker chose to conceal this entirely, showing Turner killing his master—who in the film is still his original master Mr. Turner—but showing the wife weeks later, having survived the attack, and saying nothing about the children. The conspirators then went from house to house, killing every white inhabitant and recruiting more co-conspirators. Turner’s confession described each killing in horrifying detail.

By morning there were about 60 of them, and they set off for the town of Jerusalem. The alarm had been spread throughout the neighborhood by then, and a party of armed white men confronted, attacked and scattered the rebels before they reached the town. Thus there was no climactic battle in the town square such as the movie depicts. The battle allows Parker to give the impression that a large number of the white casualties were armed men killed in a fair fight, and the closing caption states only that “60 family members” were killed by the rebels. The killing of women and children is never shown.

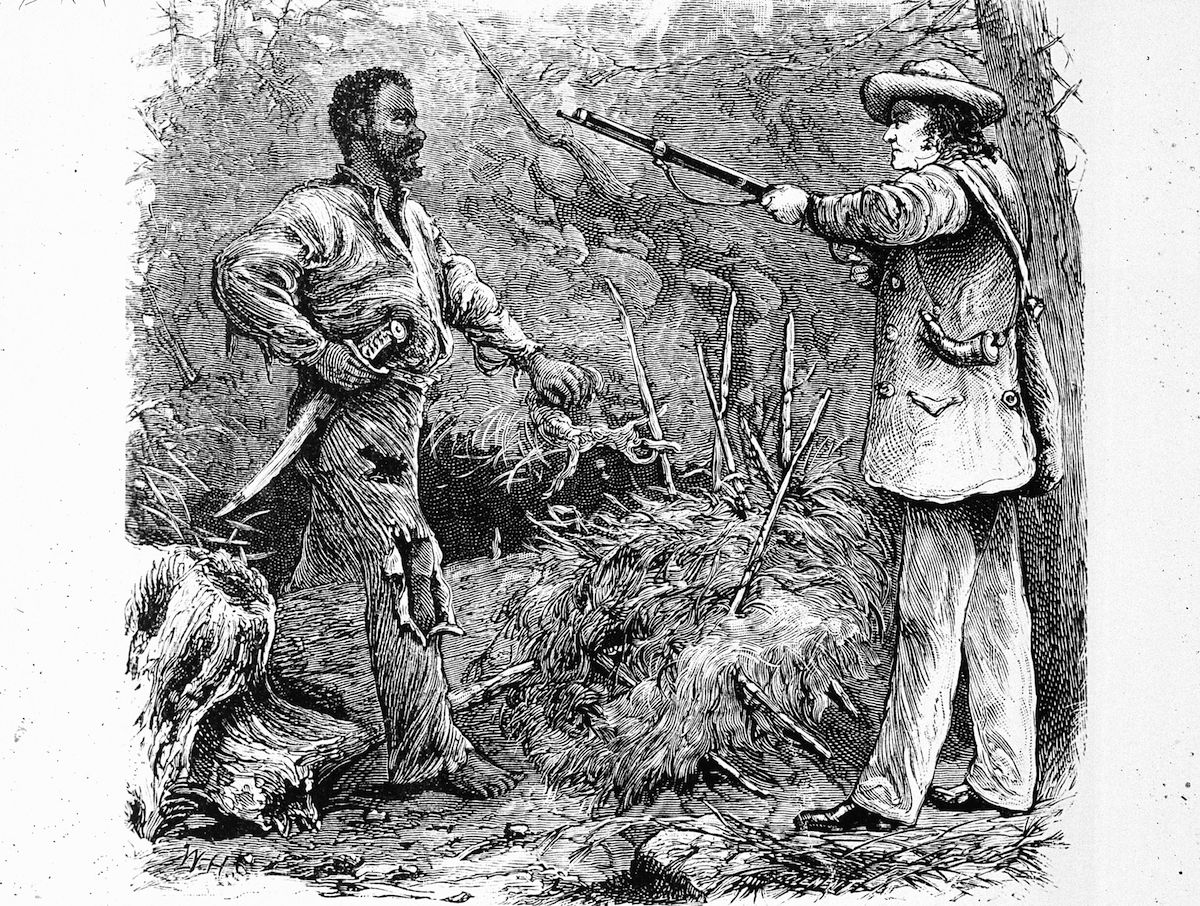

Turner did not, as the movie shows, surrender himself to stop the reprisal killings of black people, only to be fallen upon by a white mob. He was discovered by two black men after hiding in a hole in a field for six weeks, and they apparently alerted a white man, who came upon Turner armed but accepted his peaceful surrender. His confession made a great impression upon his interrogator, who asked him to say if other insurrections had been planned elsewhere. He assured them that they had not. (Of the slaves who were tried or examined in the wake of the insurrection, 17 were discharged or acquitted, and some of those found guilty were “transported”—presumably sold elsewhere—rather than hanged.)

Slaves resisted in many ways, from random acts of violence to running away to the North. Turner passed up one chance to do so, and he might easily have become a prominent abolitionist like Frederick Douglass or a clergyman in a free state. But instead, as he explained in his own words, he believed himself chosen by God to bring about the Day of Judgment, by leading a massacre of men, women and children. The evil of slavery was bigger than all the men and women, black and white, whom it touched, and Turner’s rebellion was one of its consequences. But if we deny either the barbarism of the institution or the barbarism of Turner’s response, we increase the chances that we might sink into barbarism again.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com