The National Park Service on Tuesday will release a first-of-its-kind report on the country’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender population.

The 1,200-page LGBTQ study is being published as part of the agency’s effort to preserve more places that have significance for “underrepresented” populations, including Latinos, Pacific Islanders and Native Americans.

The report says American history has long focused its celebrations on straight white men. Out of more than 90,000 places on the list of National Historic Landmarks and the National Register of Historic Places, just 10 are currently listed explicitly because of their historic significance for LGBT people, who make up an estimated 5% of the U.S. population (or more, depending how you’re counting).

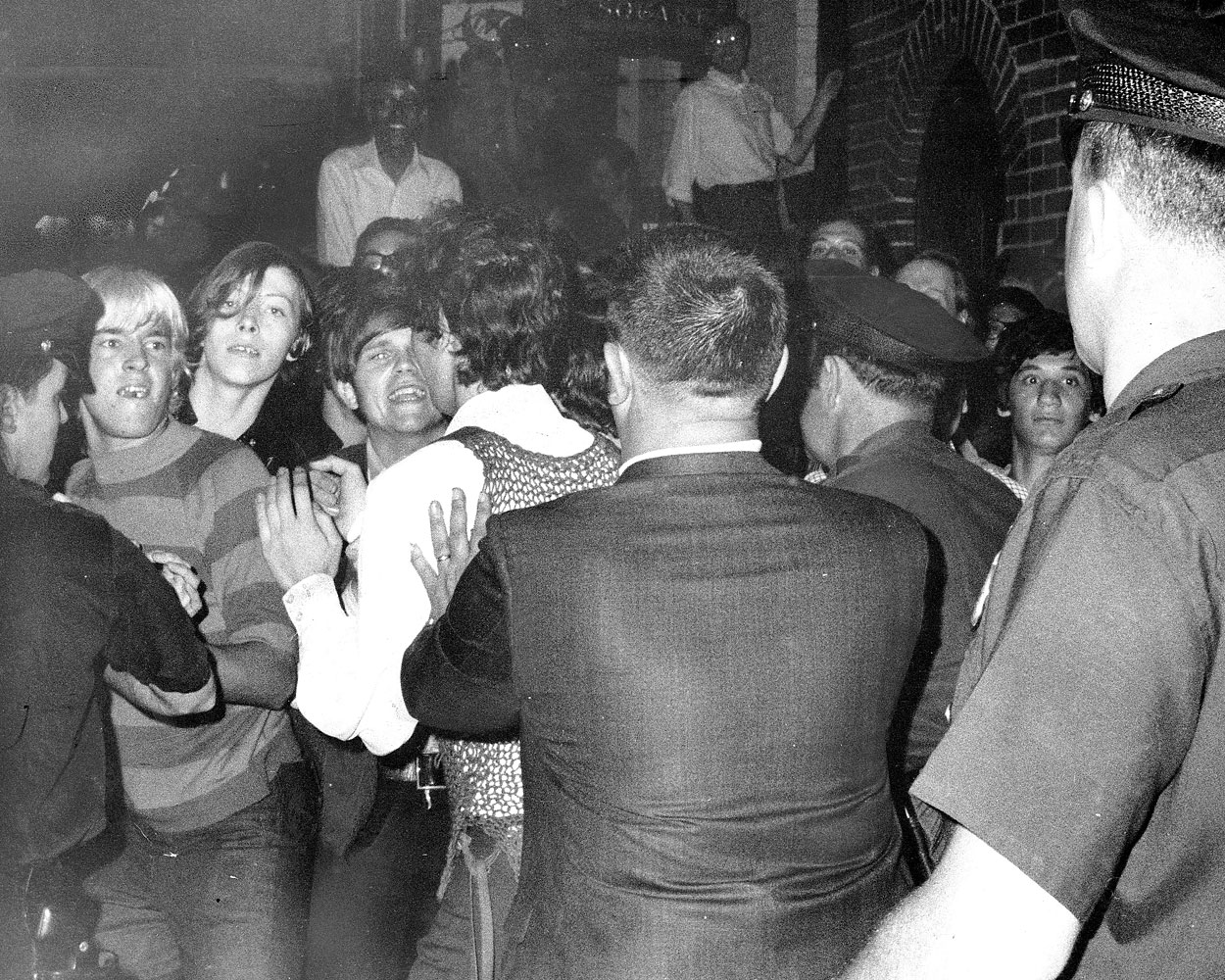

One of those places, New York City’s Stonewall Inn—where riots helps spark the gay liberation movement in the 1970s—became the first national monument to celebrate LGBT history earlier this year. And many other locations have similar ties to that diverse population’s social and political struggles.

The report, with chapters written by academics, journalists and activists, does not anoint any places as historic landmarks or historic places. Its aim is to make the case for why roughly 1,300 locations—from private homes to courthouses to beaches–deserve recognition and is meant to serve as a kind of guidebook for individuals who might nominate those places or others like them in their own communities.

Also among the locations are hospitals, bathhouses, hotels, parks, bridges and bars, which became especially important safe places for the gay community during the past 50 years, despite the fact that there were laws on the books forbidding bartenders to serve gay or lesbian customers as late as the 1960s. Among the 10 sites currently listed as historic is a New York City bar where activists staged a “sip-in” to challenge such laws in 1966, announcing they were homosexual, thirsty, and not leaving until they were served. The law was soon changed.

Part of the study’s aim is to identify locations beyond the obvious coastal “meccas” where LGBT people have made history and to include stories that might not have been deemed “respectable” in the past, whether that’s because those stories are about intimate relations or about transgender sex workers who have been thought to hamper the image of the gay rights movement.

“Where the very definition of what it means to be lesbian, gay, queer, or bisexual is based on attraction and intimacy, sex cannot be ignored,” writes the study’s editor, Megan Springate. For people who were rejected because of their sexual feelings, she notes, locations like known cruising grounds can have serious significance. Beyond that, she adds, “Much of [LGBT] history is difficult; it is about loss, violence, struggle, and failure.” Take, for example, the fields of unmarked graves that hold the bodies of people who died from AIDS in the 1980s.

There were some challenges in writing this report that wouldn’t crop up with populations that were marginalized because of race or other factors. For centuries, laws explicitly forbade people to act on same-sex attractions or to wear the clothes of the opposite sex. And words like homosexual and transgender have only been common parlance since the 1900s. That means many historical figures who might have been LGBT might never have said so out loud, even if was known, say, that a pioneering woman only had two significant relationships in her life—both with other women.

But the long-decried invisibility of sexual and gender minorities is also the reason that the study’s authors believe the identification and inclusion of these places to be so important.

“In the [LGBT] community, where discovering who one is and accepting that identity is often challenged by the surrounding society, discovering tangible physical echoes of that identity can underpin queer youth’s self-acceptance and reinforce a sense of belonging,” writes queer historian Mark Meinke. “In my youth in a small midwestern town, there was no support and there were no sources of information. There were no queer-identified places that would reassure me that I was not a hateful anomaly.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com